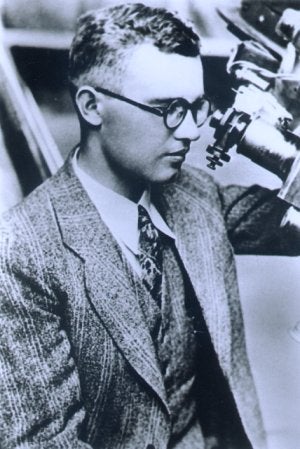

The oldest of Muron and Adella Tombaugh’s six children, Clyde Tombaugh was born in Streator, Illinois, in 1906. He became interested in astronomy early in his childhood, and in his later years often remembered with fondness the excitement he felt when his uncle Lee gave him his first telescope, a 3-inch refractor. By the time Clyde’s parents moved the family to a rented wheat and corn farm in Burdett, Kansas, in mid-1922, Clyde was already an avid amateur. In high school, he played track and field, dabbled in Latin, and played football with his friends on weekend afternoons. Too poor to afford college, Tombaugh accepted the job at Lowell Observatory equipped with a high school education and a strong desire to become a working astronomer.

Tombaugh arrived in Flagstaff from Kansas by train on the wintry afternoon of January 15, 1929. He carried with him a single trunk, weighed down more heavily with books than clothes. Clyde didn’t know he was being brought to Flagstaff to search for Planet X, only that he would be involved in “photographic work.” It was on his arrival that Tombaugh learned the true nature of his job.

A new, wide-field, 13-inch telescope and associated camera had been commissioned for the search. But when Tombaugh arrived at Lowell, the equipment still wasn’t ready. Instead, he made himself useful with tasks around the observatory that included giving tours, shoveling snow, and stoking the furnace. Clyde’s father Muron had told his son to “Make yourself useful,” and Clyde intended to, but this was a pretty humble beginning. Mercifully, by early April, the new telescope was finally ready, and Tombaugh could begin doing some astronomy.

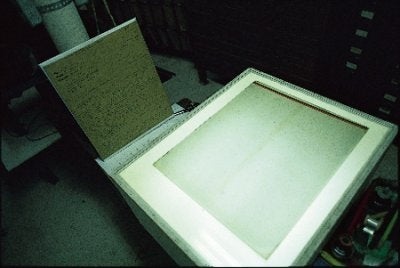

Initially, Vesto M. Slipher, the observatory’s director, tutored Tombaugh: “X” was expected to be at least 15 times fainter than Neptune. They would have to make long, deep exposures of the sky so the photographic plates could soak up enough light to detect the prospective planet. Since planets move perceptibly from night to night but stars do not, the key would be to spot a faint, slowly moving target against the backdrop of stars and galaxies. To do this, each plot of sky would be photographed three times during the course of several nights. Each plate had to be exposed for an hour or more to detect the faint phantom they were hunting, and Clyde would have to precisely adjust the telescope to keep pace with the turning sky throughout each exposure. To ensure the darkest possible sky as an aid to spotting the faint wanderer, images were made only around the time of new moon.

After a few nights of lessons with Slipher, Tombaugh was taking images on his own. Within a few weeks, Tombaugh was also given the responsibility of inspecting the plates for evidence of the hoped-for planet. Because only Lowell Observatory was still searching for ‘X’, and only Clyde was working on the task at Lowell, the fate of the ninth planet search rested entirely with one, very young man.

A few months passed and Clyde realized that the most efficient place in the sky to search for a distant planet would be precisely at the spot where its motion, as seen from Earth, would be both fastest and most noticeable, the “opposition point.” By working at the opposition point, Tombaugh knew he could easily distinguish a distant, slowly moving planet from the numerous, nearby asteroids that also peppered the plates but move much more quickly across them. This crucial advance made the detection of his distant prey much more straightforward.

It wasn’t easy. It wasn’t glamorous. It wasn’t even very interesting. Fortunately, Clyde’s commitment was monumental. And so was his concentration – which he needed to combat the sheer drudgery of methodically inspecting hundreds of plate pairs, each of which contained 50,000 to 900,000 stars, looking to see if one faint, point of light on it might move a bit from night to night.

Clyde blinked plates slowly, for hours on end. But he had to take frequent breaks to clear his mind so he could keep concentrating. The penalty for missing the suspected prey was too great to permit his mind to become dulled by the tedium. Clyde set out to be a perfectionist about the task – something that demanded nearly Herculean concentration.

Tombaugh told me in 1996 that few people, even astronomers, “have any concept of the grim (plate comparison) job that V. M. Slipher gave to me.” And he was right! Today no one would stand for such a job – a computer would make the comparisons. But the late 1920s were another time, laden with a wholly different set of technologies. It was a time when the ocean was crossed by steamship, human operators moving cables across a board made phone connections, and most iceboxes actually used ice delivered from distant frozen lakes. So too, the technology for comparing astronomical images was, by today’s standards, frighteningly primitive.

By the time he blinked a month’s worth of newly developed plates, the opposition point would have moved. So Clyde would photograph a new region, develop the plates, and blink those too. And so on. And so on. During the course of his search, Tombaugh found more than 29,000 galaxies, 1,800 variable stars, and two new comets.

By February 1930, Clyde Tombaugh had worked his way around the ecliptic to the constellation Gemini. He had made a few test plates in this region in early 1929 when the 13-inch telescope was first being set up, but that was before he hit upon the idea of using the opposition point to make distant-planet detections easier and more systematic. This time, however, Tombaugh ran right into his prey, and caught it.

It was the 18th of February when Clyde examined his plates of the star field around Delta Geminorum, the fourth brightest star in Gemini. There, a faint 15th-magnitude pinprick of light equivalent to a candle seen from a distance of 300 miles (480 kilometers) lost its four-billion-year-old anonymity.

In the sky, there are 15 million stars brighter than the pinprick Clyde spied hopping across a corner of the Gemini star fields. Blink comparing the position of the anonymous little pinpoint between the various January plates, allowed him to see it move.

It didn’t jump very far, only three or four millimeters. The fact that the jump was so small was the exciting part, for it indicated that if the object was real, then it surely lay beyond Neptune. “That’s it!” he said to himself, but in his logbook, his very own “X” files, Tombaugh simply wrote, “planet suspect” and the coordinates of the tantalizing speck of light. It was 4 p.m. (More than 65 years later Tombaugh loved recalling how he discovered the ninth planet, “during the daytime!”)

After he finished inspecting the plates, Tombaugh set out to confirm whether the faint little nomad was indeed real. The test he applied was deceptively simple, but stunningly powerful. Clyde had taken three other plates of the same region on the same nights, using the smaller, 5-inch telescope that he had boresighted onto the 13-inch as a kind of finder scope.

The planet-suspect had to appear in the same place on the check plates as well if it was real. Bingo! The little wanderer appeared right where it should! For nearly three-quarters of an hour, as he checked and crosschecked the moving pinpoint among the various plates, Clyde Tombaugh was the only person in the world to know that Planet “X” had very likely been found.

Trembling with excitement, he went to see his boss, Slipher, and Lowell’s assistant director, Carl Lampland. Standing at the door of Slipher’s office, Tombaugh announced, “I have found your planet X.” Clyde had never before come to make such a statement. Slipher stood up from his chair, and with Lampland, rushed to the blink comparator to check Tombaugh’s plates. The two older men shortly confirmed Clyde’s findings. Slipher’s order: “Don’t tell anyone until we follow it for a few weeks. This could be very hot news.” Excited, but cautious, Slipher wanted more evidence.

The Lowell astronomers spent the next three weeks checking and monitoring the motion of the new planet. Amazingly, during all this time, no one breathed a word of it beyond themselves and their immediate associates.

Within days, Lowell Observatory was inundated with reporters, and Clyde Tombaugh was world famous. Today Clyde’s discovery would probably net the standard Warhol allotment of 15 minutes of fame, but thankfully, in 1930, things lasted a little longer. The media rush lasted for months.

Later in 1930, the Lowell Observatory staff selected the name Pluto, after the Greek god of the underworld, and in honor of Percival Lowell (whose initials are P. L.). Lowell’s search was complete, and our view of the outer solar system had been changed forever.

Despite the media crush, Tombaugh didn’t let up from the search, which he expected would likely yield more discoveries. In fact, Tombaugh continued his search for additional planets from Lowell during the 1930s and into the early 1940s. Although he found no more worlds, his survey did reveal numerous new asteroids, another comet, a nova, a globular cluster, five open clusters, and the Andromeda-Perseus supercluster.

Also during the 1930s, Tombaugh married and went back to Kansas to earn bachelor’s and master’s degrees in astronomy from the University of Kansas. After leaving Lowell on difficult terms, he taught navigation for the U.S. Navy during World War II, and then became involved in early rocketry at White Sands Proving Grounds in New Mexico after the war. In 1955 he left the rocket business to join the faculty of New Mexico State University, where he built a strong program of planetary astronomy. His research efforts during that period included a search for small satellites of Earth, studies of Mars that led him to correctly conclude (in 1950!) that Mars would have large impact craters, and studies of galaxy clustering that are a respectable forerunner of modern extragalactic work. According to his biographer David Levy (of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 fame), Tombaugh received a total of at least 36 awards, citations, and honorary degrees during his long career, which officially ended in retirement in 1973. Despite the lasting fame that Pluto’s discovery brought him, Clyde remained a private man, with great humility and warmth.

Although Tombaugh retired in 1973, he kept an office and remained active in astronomy until late 1996. During retirement he focused on public outreach activities, and writing. He co-authored, with Patrick Moore, the book, Out of the Darkness: The Planet Pluto. Clyde was an inveterate punster and a man of great energy, even in retirement. When the Smithsonian Institution asked him to contribute his 9-inch telescope to its collections, he replied characteristically, “They can’t have it – I am still using it.”