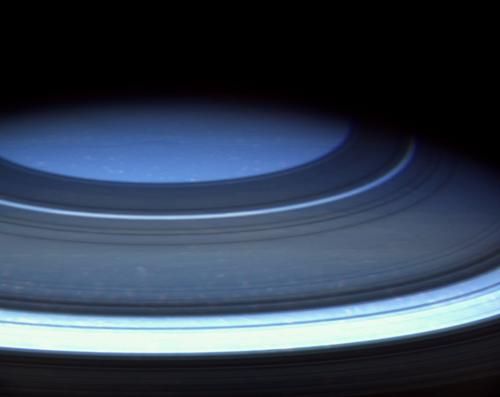

Saturn’s northern hemisphere is presently a serene blue, more befitting of Uranus or Neptune, as seen in this image from Cassini.

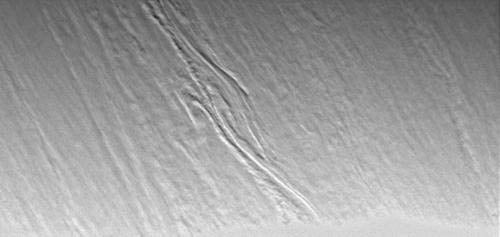

Clouds near the boundary of day and night on Saturn show unusual three-dimensional structure in this Cassini view. At this location on the planet, the Sun is at a very low angle, causing vertical relief to become apparent. Generally, Cassini imaging scientists use specially designed spectral filters to probe the vertical structure of the gas giant’s atmosphere.

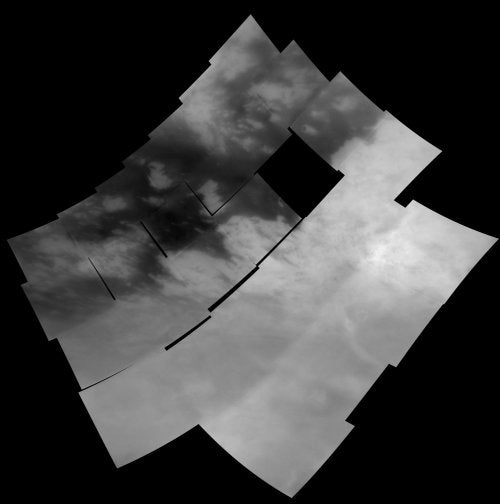

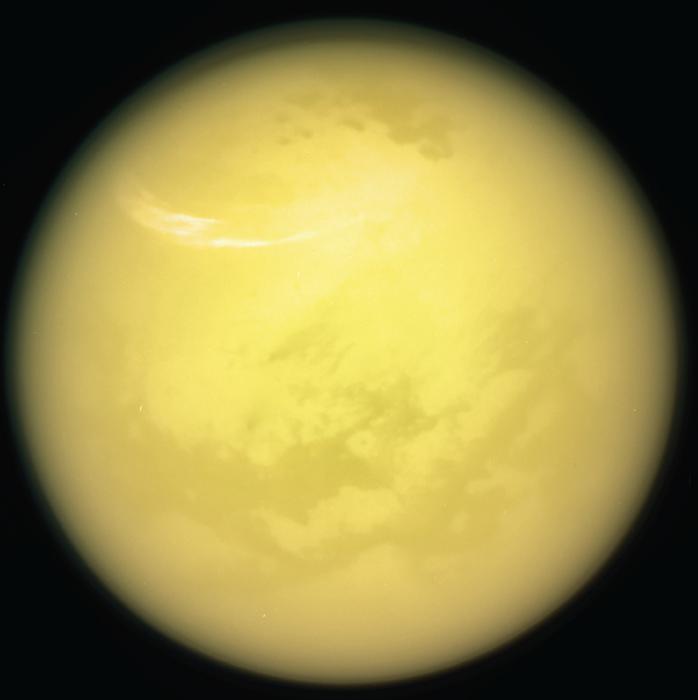

A mosaic of 28 mid-resolution images shows the broad area Cassini covered during its first close flyby of Titan October 26. The bright region at right, known as Xanadu Regio, stands in sharp contrast to the dark terrain at left. Several small, bright features, between 20 and 125 miles across, appear within the dark terrain

NASA / JPL / Space Science Institute

A mosaic of 28 mid-resolution images shows the broad area Cassini covered during its first close flyby of Titan October 26. The bright region at right, known as Xanadu Regio, stands in sharp contrast to the dark terrain at left. Several small, bright features, between 20 and 125 miles across, appear within the dark terrain.

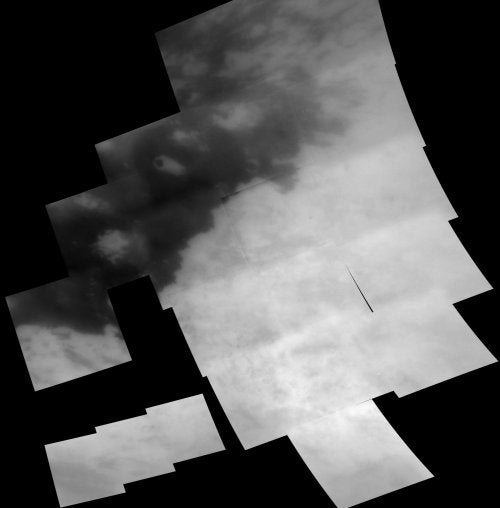

This mosaic of 28 mid-resolution images shows the major areas Cassini saw during its second close flyby of Titan December 13. The region covered includes some areas seen in October and additional regions to the north and east. The northern boundary between the bright and dark terrain appears more complex than the sharp boundary farther south.

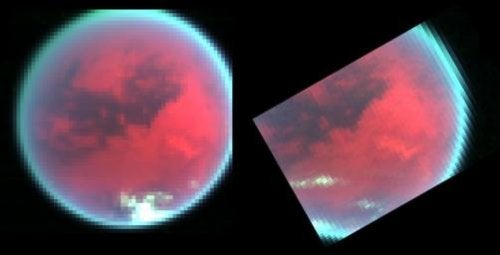

Titan’s weather changed significantly between October and December. These two false-color views, taken with the Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer, show Titan on October 26 (left) and December 13. In October, the only clouds visible were near the moon’s south pole. In December, however, extensive clouds also appeared at mid-latitudes.

NASA / JPL / University of Arizona

Titan’s weather changed significantly between October and December. These two false-color views, taken with the Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer, show Titan on October 26 (left) and December 13. In October, the only clouds visible were near the moon’s south pole. In December, however, extensive clouds also appeared at mid-latitudes.

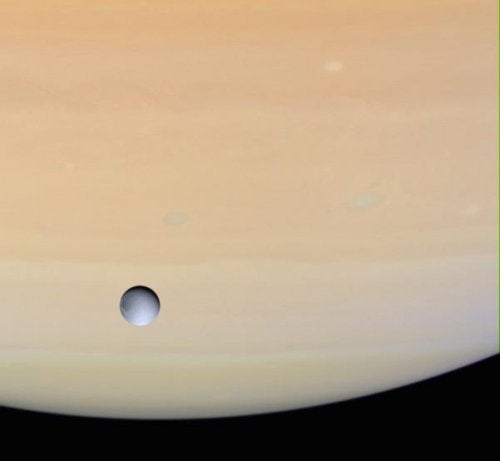

Dione hangs in front of Saturn as the Cassini spacecraft approaches December 14. This natural-color view shows a distinct lack of color on Dione, at least compared with the warm hues of Saturn’s cloud tops. Cassini was 375,000 miles from Dione when this image was taken.

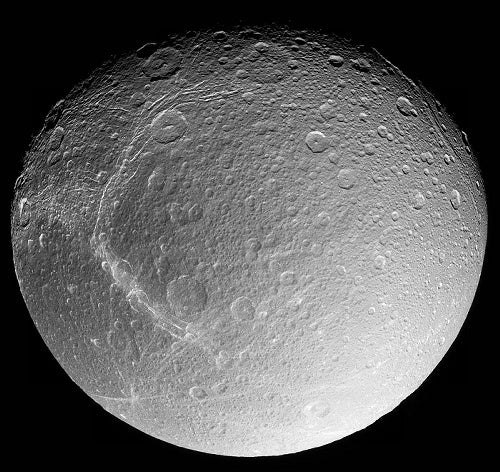

Heavily cratered Dione shows up in greater detail here than in any image taken during the Voyager missions of the early 1980s. This view highlights some of the linear and curving features of Dione’s wispy terrain. It was taken from a distance of 97,000 miles.

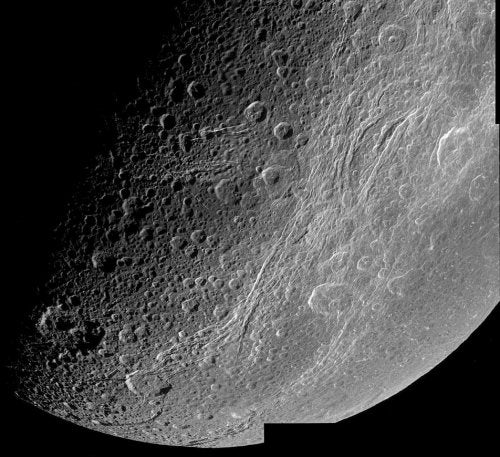

Cassini snapped this image of Dione at closest approach, when the spacecraft came within 50,000 miles of the moon’s surface. The view highlights the moon’s wispy terrain, which planetary scientists thought consisted of thick ice deposits. However, the Cassini images have convinced researchers the markings are bright ice cliffs created by tectonic fractures.

NASA / JPL / SSI

Cassini snapped this image of Dione at closest approach, when the spacecraft came within 50,000 miles of the moon’s surface. The view highlights the moon’s wispy terrain, which planetary scientists thought consisted of thick ice deposits. However, the Cassini images have convinced researchers the markings are bright ice cliffs created by tectonic fractures.

Cassini snapped these photos of Saturn’s moon Iapetus in October, giving scientists their closest look ever at the enigmatic moon. These views show the side of Iapetus that faces away from Saturn. Half of the moon appears as bright as newly fallen snow, while the other half is as dark as a freshly tarred parking lot. Craters abound in both regions, and at least one large impact basin some 250 miles across (seen in the lower half of the images) mars the surface. Also note the line of mountains cutting through the top half of the images.

NASA / JPL / SSI

Cassini snapped these photos of Saturn’s moon Iapetus in October, giving scientists their closest look ever at the enigmatic moon. These views show the side of Iapetus that faces away from Saturn. Half of the moon appears as bright as newly fallen snow, while the other half is as dark as a freshly tarred parking lot. Craters abound in both regions, and at least one large impact basin some 250 miles across (seen in the lower half of the images) mars the surface. Also note the line of mountains cutting through the top half of the images.

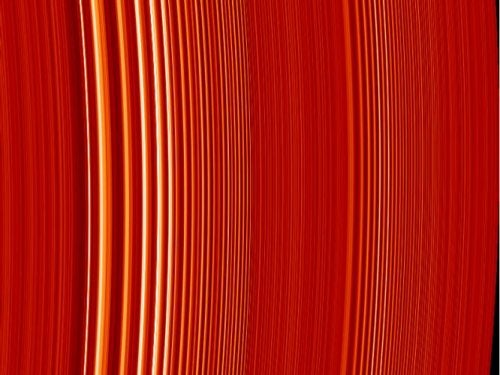

Cassini’s Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph observed the star Xi Ceti as Saturn’s rings passed in front of it. Then, the flickering of the starlight was converted into the ring density seen in this image (bright areas mark regions of higher density). The bright band in the left of the image results from gravitational perturbations induced by the small moon Janus; the fainter band to the right is caused by the moon Pandora.

NASA / JPL / University of Colorado at Boulder

Cassini’s Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph observed the star Xi Ceti as Saturn’s rings passed in front of it. Then, the flickering of the starlight was converted into the ring density seen in this image (bright areas mark regions of higher density). The bright band in the left of the image results from gravitational perturbations induced by the small moon Janus; the fainter band to the right is caused by the moon Pandora.

As it completed its first orbit of Saturn, Cassini captured this view of the shepherd moon Prometheus. The tiny satellite, measuring 63 miles across (102 kilometers), is exercising its influence on the multi-stranded and kinked F ring. The F ring resolves into five separate strands in this closeup view. Potato-shaped Prometheus is seen here, connected to the ringlets by a faint strand of material. Imaging scientists are not sure exactly how Prometheus is interacting with the F ring here, but they have speculated that the moon might be gravitationally pulling material away from the ring. The Cassini spacecraft imaged this thievery October 29, 2004.

NASA / JPL / Space Science Institute

The small moon Prometheus shepherds particles in Saturn’s F Ring, which resolves into five ringlets in this close-up view. A thin strand of material connects the ringlets to potato-shaped Prometheus, which measures 92 miles at its widest. Planetary scientists speculate the moon’s gravity may be pulling material from the F Ring.