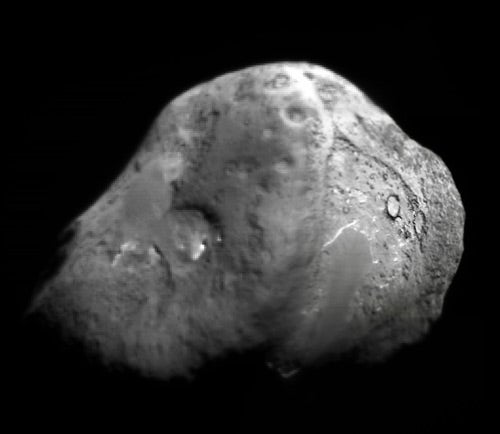

As the 820-pound (370 kilogram) copper probe zoomed toward its target — Comet 9P/Tempel 1 — a camera on the probe captured its descent. Scientists were able to resolve objects on Tempel 1’s surface 13 feet (4 meters) in diameter — 10 times more detailed than ever seen before.

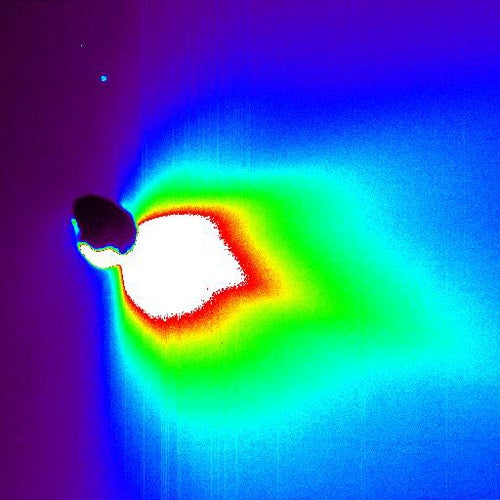

Once the probe plowed into Tempel 1 — at 23,000 mph (37,000 km/h) — two cameras on the Deep Impact mothership watched and recorded the impact’s aftermath. Even ground-based telescopes imaged the impact it was so bright.

The cloud of material dissipated after 10 days, and as of now, astronomers are trying to find the crater.

Astronomers detected only a small amount of water vapor and other gases. In fact, the comet had a post-impact water-vapor emission rate similar to pre-impact rates, according to astronomers observing with the Submillimeter Wave Astronomy Satellite. This implies the probe didn’t create a crater deep enough to see below the rind. So the radiation-damaged surface must extend deeper than just a few yards.

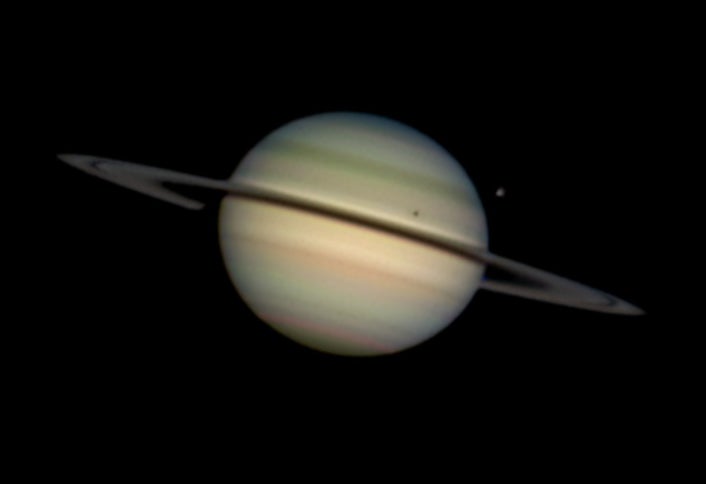

What really happens to comet nuclei out in space? Astronomers have analyzed the surfaces of four comets through spacecraft flybys, none of which looks alike. Slamming a projectile into one didn’t quite unlock as many secrets as we hoped, but landing on one might. Here’s to the Rosetta comet mission and its spacecraft — Philae — that will land on a comet’s surface.

Rosetta was launched in March 2004, and Philae is projected to land on comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko in the summer of 2014. Let’s keep our fingers crossed for this one.