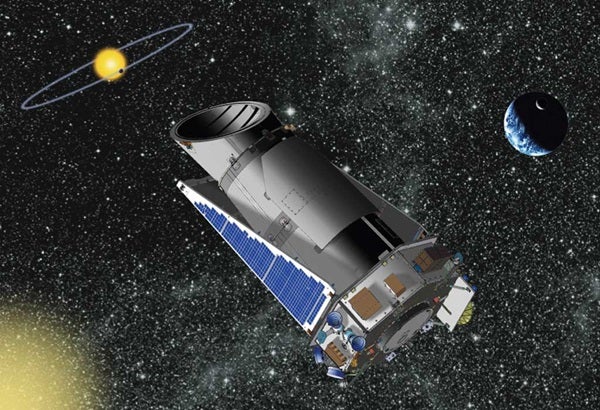

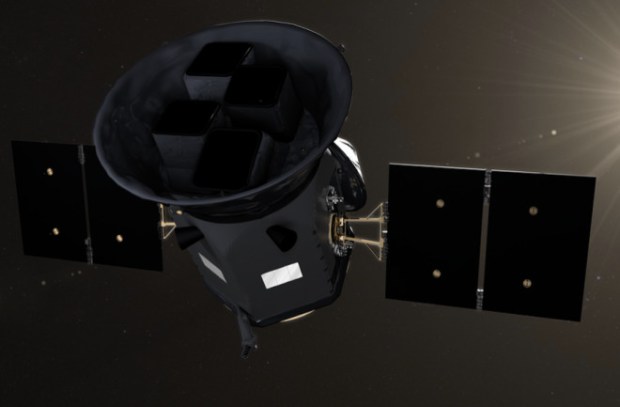

Exoplanet science — or the search for planets other than those eight in our solar system — has been a hot topic in the past few years, especially since the launch of NASA’s Kepler spacecraft. Its sole mission is to search for planets and to home in on ones that are rocky and potentially habitable. Kepler stares at the same patch of sky and watches for transits: times when an object passes in front of its star, blocking out a tiny amount of the star’s light. This tiny dip in brightness alerts astronomers to potential planets. One transit isn’t always enough, though, as stars are big and planets are small. So Kepler watches not just for one, but multiple dips that occur at regular intervals. An alien scientist watching the Sun would see a dip in the Sun’s apparent brightness once every 365.24 Earth days, when the Earth passed between the alien and our star. But they might have to see it more than once and combine the data together to be sure the detection is real before they hop on their spaceships and spend the next 10,000 years traveling here.

How many planets surround other star systems?

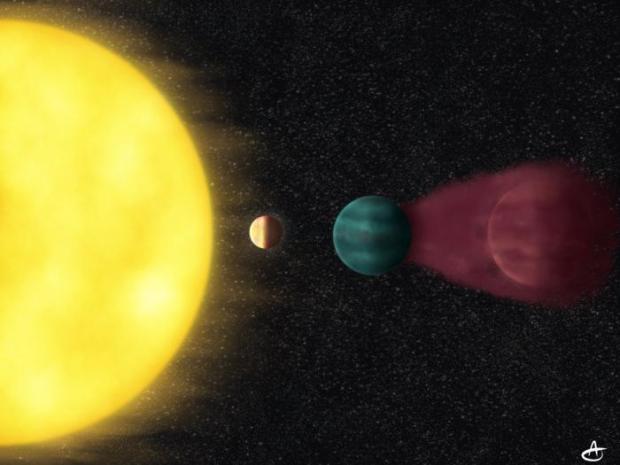

Although scientists are still analyzing data from the ever-productive Kepler spacecraft, the results that are in are enough to say one thing: A lot of planets are out there. Fifty percent of all stars have a planet that is Earth’s size or bigger in close orbit. Interested in Earth-sized-or-larger planets in bigger orbits? The number jumps to 70 percent. And if you pick any solar system with a Sun-like star, you are almost guaranteed to find a planet or two. The Milky Way — and by extrapolation, the rest of the universe — is full of rocky and gassy bodies orbiting central stars. It is home to at least as many and possible more planets as stars. As of June 2013, astronomers had confirmed 892 and had thousands more candidates. Go to http://exoplanet.eu/ to check out the data and make your own diagrams using information about the planets’ orbits, masses, and radii.

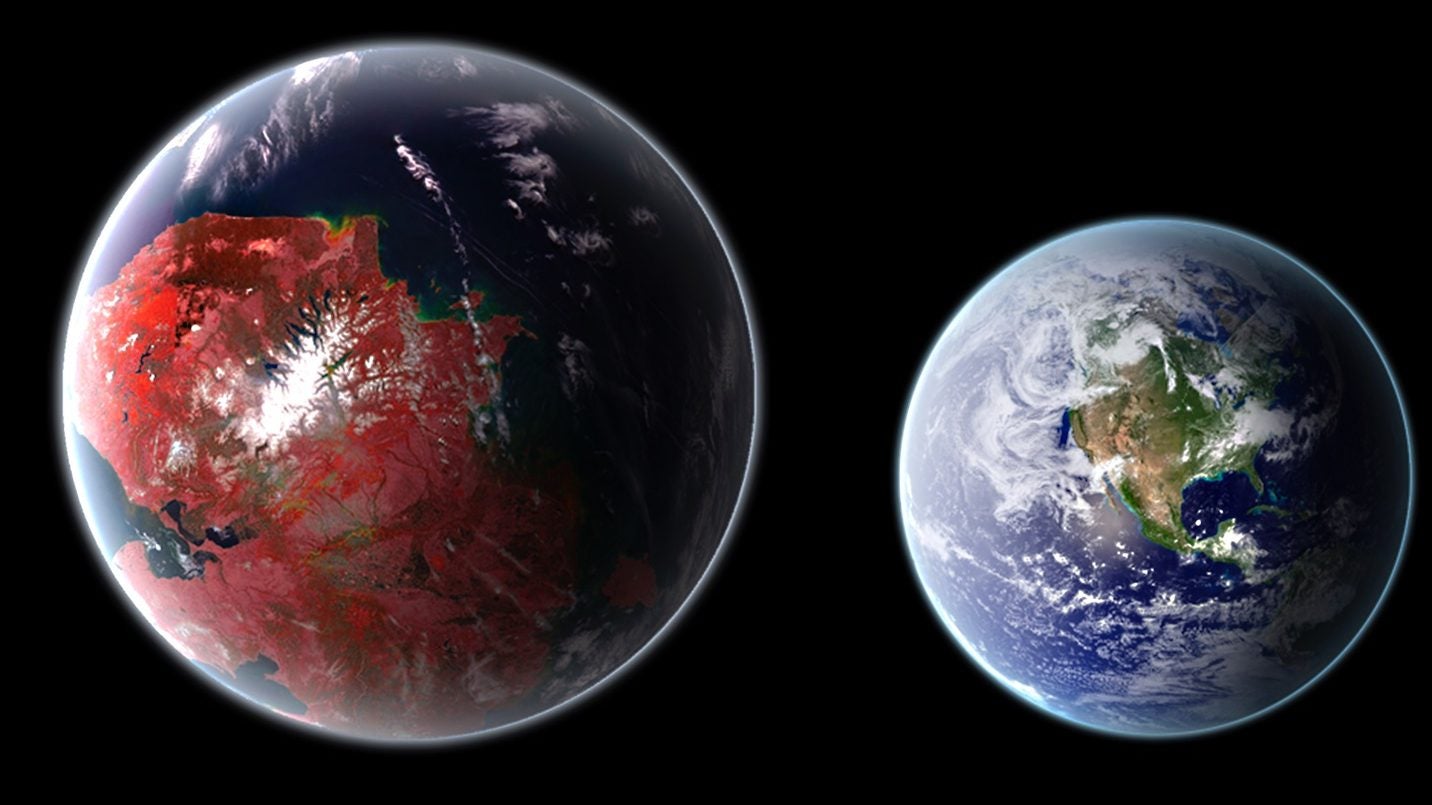

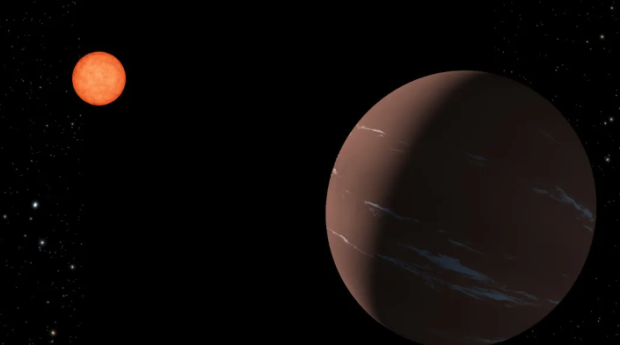

Are there other planets like Earth?

According to Kepler’s latest estimates, one out of every six stars has an Earth-sized planet in a close (i.e., warm or hot and not icy) orbit. Further investigation will show exactly how “like Earth” these Earth-sized planets are. They have to be rocky, and they are not extremely cold. But do they have water? Do they have atmospheres? Do the chemicals in their atmospheres show any evidence that life is down on their surfaces metabolizing? Each planet will be slightly different, but out of the ones scientists have found, the candidates they will confirm, and the ones they will discover in the future, some are likely to be similar to our own planetary home. Read about the initial finding here.