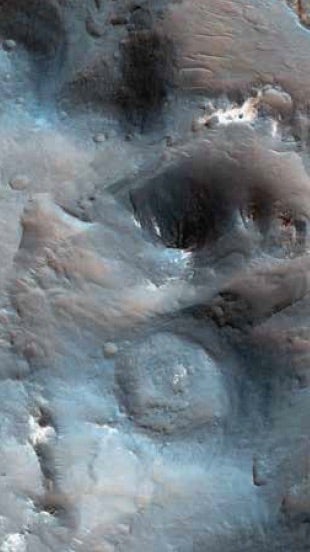

A good chunk of that data comes from the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE), on which I am the principal investigator. The camera has acquired more than 52,000 high-resolution orbital images of Mars’ surface. The photos achieve resolutions as high as 10 inches (25 centimeters) per pixel, good enough to measure objects as small as 30 inches (75 cm) across.

Engineers at Ball Aerospace in Boulder, Colorado, designed and built the camera. We call it “The People’s Camera” because we process and release images quickly, provide tools to make it easier to examine these enormous images (which can contain up to 500 megapixels), and welcome suggestions from the public.

HiWish is our public web tool for suggesting images. It’s easy to register and propose places on Mars you’d like HiRISE to photograph. Since we announced the HiWish program in early 2010, 9,248 people have registered, and they have put forward 21,021 targets. Sometimes a single photo can satisfy more than one suggestion if the locations lie close enough to one another. As of the beginning of this year, HiWish has fulfilled 7,000 requests by capturing 5,483 images, about 10 percent of HiRISE’s total.

A HiWish user first decides what he or she wants to image, then writes a brief science justification and selects one of 18 science themes. (See “The 18 science themes,” starting on p. 25, for descriptions.) Next, a member of the HiRISE science team prioritizes suggestions in each theme. A science lead chooses which of these to favor in each two-week MRO planning cycle. The decision takes into account several constraints, including the recommended priorities and what regions MRO will be able to view during that two-week window.

We typically need at least one image per 120-minute orbit to make optimal use of the downlink, or data stream, to Earth. HiRISE photos are so large that we can’t store more than a few of them on board the spacecraft at a time; luckily, NASA’s Deep Space Network provides downlink coverage every day. But if we take too few images, we will have transmitted all of our data and be left with valuable downlink that goes unused.

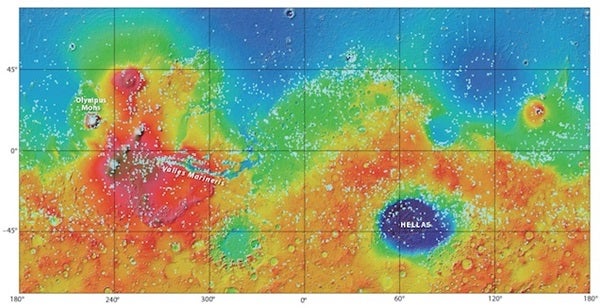

If you look at the global distribution of images acquired through the HiWish program (see p. 22), you’ll see only a smattering in Mars’ polar regions. This may be because the base maps people use to target the camera are incomplete or difficult to interpret at high latitudes. Away from the poles, the distribution is remarkably uniform in comparison to a map showing all HiRISE images, which concentrate strongly in certain locations. This happens because we commonly acquire HiWish images in regions that would otherwise have few science targets.

HiWish users include scientists who are not part of the HiRISE team, and as you might expect, they enter great science suggestions. University of Hawaii researcher Peter Mouginis-Mark proposed the first HiWish image we acquired: a view of ejecta flow from the 15.4-mile-wide (24.8 km) crater Arandas. Some of our favorite HiWish requests come from Ken Edgett of Malin Space Science Systems in San Diego. Edgett is the principal investigator for the Mars Hand Lens Imager on the Curiosity rover and was the top planner of photos captured by the Mars Orbiter Camera on the Mars Global Surveyor satellite from 1997 to 2006. Roughly 100 other Mars scientists have suggested targets, and the resulting images have contributed to hundreds of publications.

Still, you don’t need to be a Mars scientist to propose excellent targets. Although each proposal needs a science rationale, it can be something as simple as “This hill looks like a volcano in lower-resolution images or topography, but we need a better image,” or “This feature is especially bright in THEMIS nighttime infrared images — I wonder what it is.”

THEMIS — the Thermal Emission Imaging System aboard NASA’s Mars Odyssey spacecraft — photographs the martian surface at five visible-light wavelengths and 10 infrared wavelengths. Areas that appear bright in the infrared at night are warm and thus typically rocky, and bedrock makes a great subject for HiRISE. Regions that appear dark and featureless at night are cold and tend to be covered with dust. Such locations typically make less interesting targets for high-resolution photography, though with some important exceptions, like new impact sites.

Of the 5,483 HiWish images, retired schoolteacher James Secosky suggested 2,133 — nearly 40 percent of the total. He is also largely responsible for the excellent Wikipedia page about HiWish. The page includes many of his favorite HiWish images broken down into 35 categories. Secosky chooses his desired locations by first examining photos taken with MRO’s Context Camera (CTX), which provides a resolution of about 20 feet (6 meters) per pixel. Features that look interesting in a CTX image usually make great targets for HiRISE.

Many proposals come from students. Over the past decade, Ginny Gulick of NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, has helped students at Evergreen Middle School in Cottonwood, California, suggest and analyze HiRISE photos. And students taking my Mars class at the University of Arizona have been targeting and analyzing HiRISE images since 2007.

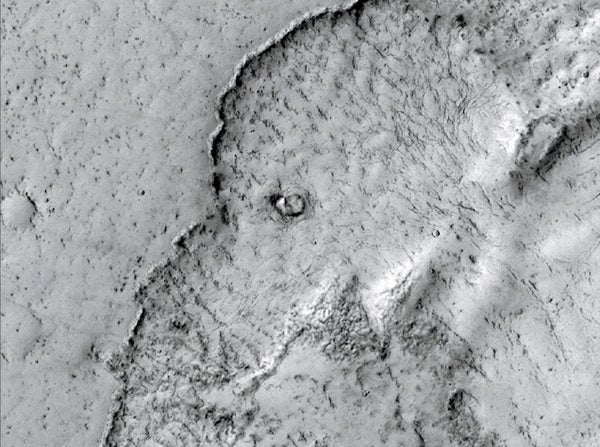

The greatest HiWish success stories are the probable discoveries of the Soviet Union’s 1971 Mars 3 lander and the United Kingdom’s 2003 Beagle 2 lander, which hitched a ride to the Red Planet on the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Mars Express mission.

Imaging successful landers is quite easy because we know exactly where to look for them and what pieces to find — typically a back shell and attached parachute, a heat shield, and the lander itself. But lander missions that failed to call home are much more difficult to find or recognize because they could lie within a large region of the planet and we don’t know for sure what to look for. If the spacecraft crashed, there might be only a small fresh crater. If the spacecraft’s parachute opened, it might create a bright target that would be relatively easy to see, and the other pieces may appear bluer, or at least less red, than a typical martian surface. Unfortunately, any such artifacts get covered by dust over time and may closely resemble natural features in HiRISE images.

Finding these lost landers requires someone — or a team — with dedication, who also understands the details of the probe’s landing system and the exact sizes of possible pieces. Russian journalist and space-exploration enthusiast Vitaliy Egorov led the Mars 3 discovery effort. In this case, at least, the spacecraft seekers had a bit of help: We know that Mars 3 landed mostly successfully because it returned a signal for about 15 seconds before going silent for still-unknown reasons. The team found an exceptional candidate for Mars 3’s parachute and more subtle features that could be the descent module, heat shield, and lander itself.

Meanwhile, Michael Croon, a retired ESA engineer who worked on the operations team for Mars Express, was searching the region more carefully. He entered a HiWish suggestion with this eye-catching science rationale: “I located Beagle 2 hardware candidates inside the 1-sigma landing ellipse, see my map … I suggest re-imaging the location (90.429E 11.526N) in color to check if the putative lander exhibits a color anomaly.”

After reading this, I made sure we acquired the requested image, which supported his interpretation. We also took additional photos, and the full set showed something remarkable: Bright spots appeared at the location of the suspected lander, but at slightly different locations in different images. We explained this as specular reflections — the type you get from a mirrorlike surface — off the solar arrays and the lander science package, each of which should be positioned on the ground at a slightly different angle.

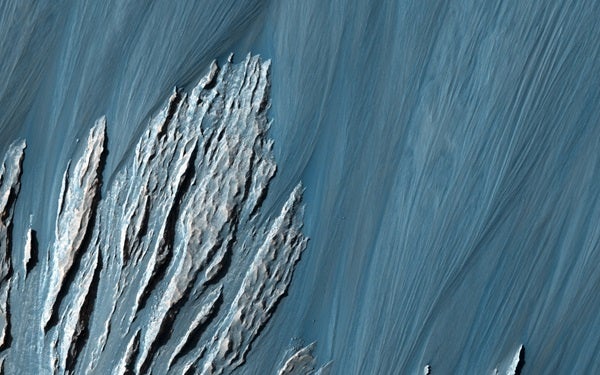

Aeolian (wind) processes: Looks at landforms sculpted by the fierce martian winds. Outside the polar regions, this is the planet’s most dynamic geological process.

Climate change: Focuses on evidence for ongoing changes in Mars’ climate by detecting signs that water and carbon dioxide are moving from one reservoir to another.

Composition and photometry: Uses the camera’s high resolution to map areas of different compositions at small scales.

Fluvial processes: Targets features carved by flowing water to learn how they formed and to better understand the history of water on Mars.

Future landing sites: Analyzes the surface and hunts for potential hazards in areas scientists are considering for upcoming landers and rovers.

Geologic contacts and stratigraphy: Looks at the way different kinds of layered rocks are arranged to determine their relative ages and how the rocks were deposited.

Glacial processes: Studies glaciers and their margins to learn about the distribution of water ice beneath Mars’ surface as well as the history of surface ice and climate.

Hydrothermal processes: Examines features and deposits that might have formed in the presence of water warmed, for example, by volcanic activity or an impact.

Landscape evolution: Seeks the subtle signatures that allow scientists to understand the processes that shape the planet’s diverse landscapes.

Mass wasting processes: Studies the downhill movement of rocks and debris, from massive landslides and debris avalanches to single boulders rolling down a hill.

Polar geology: Explores the layered deposits in both the north and south polar regions, to help unravel the planet’s climate history.

Rocks and regoliths: Examines rocks as well as the smaller rock pieces and dust (regolith) that make up the martian soil, to see what processes create this soil over time.

Seasonal processes: Studies the transient polar caps of carbon dioxide frost as they wax and wane (through condensation and sublimation, respectively) with the seasons.

Sedimentary/layering processes: Seeks insights into Mars’ layered rocks to learn when the layers formed and if they began as sediments in lakes, volcanic ash, or atmospheric dust.

Tectonic processes: Explores the forces within the planet’s interior that cause rock to slide, bend, and break, by measuring how much the rock has deformed.

Volcanic processes: Focuses on the planet’s huge volcanoes and extensive lava flows, in part to learn if the lava oozed from the ground or blasted out in massive explosions.

Other (non-themed): Any potentially interesting observation that doesn’t relate directly to one of the other 17 themes.

The scientists behind the HiWish program have developed tools to make it easy to plan your imaging adventures with HiRISE. Here are some websites to help you get started:

HiWish home page:

www.uahirise.org/hiwish

NASA’s initial announcement about the HiWish program: www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?release=2010-018

The first HiWish image acquired:

www.uahirise.org/ESP_016842_2225

HiView, a tool for viewing

full-resolution HiRISE images: www.uahirise.org/hiview

Help analyze HiRISE images:

www.planetfour.org

James Secosky’s Wikipedia page for the HiWish program:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HiWish_program

THEMIS images and background:

https://themis.asu.edu

The Mars 3 lander story:

https://tinyurl.com/yc6xlstj

The Beagle 2 discovery story:

https://tinyurl.com/m9tnwsn