History of Astronomy magazine

Learn the history of the world’s most popular magazine covering astronomy, observing, and spaceflight news.

Little did Steve Walther know that his brainchild, Astronomy magazine, would turn into the greatest magazine about astronomy in the world. At 29, the ambitious graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point launched a periodical about his first love, the stars. The first issue, August 1973, held 48 pages and five feature articles, plus information about what to see in the night sky that month.

Walther had grown up in the Milwaukee area and taken jobs in public relations after college, always dabbling in his beloved pursuit of astronomy. He worked part time as a planetarium lecturer at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and developed a keen interest in photographing constellations. His gift to the world would live on, but, sadly, he would not.

With the magazine catching on rapidly, Walther threw a party for contributing authors, photographers, and sponsors in the summer of 1976. Beside a pool, surrounded by drinks and hors d’oeuvres, talking his best game with his closest friends, Steve Walther collapsed, insensible. He died the following year, the victim of a brain tumor.

I never met Steve Walther. As he toiled through his illness, I was hundreds of miles away — a teenager — working on my own little publication, Deep Sky Monthly, a journal about observing galaxies and clusters with small telescopes. But I was fortunate to meet and make friends with many who knew him, many who had worked with him.

Astronomy magazine is reborn

Reeling from the loss of leadership, the company Walther had started — AstroMedia Corp. — brought in Richard Berry to become editor and Bob Maas to take the publisher’s helm. Together, Berry and Maas forged Astronomy into a solid, respectable, and exhilarating package showcasing the best astronomy had to offer throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Berry and his co-workers lorded over one of the most exciting periods in the history of modern astronomy, covering the Voyager missions to the planets in spectacular detail. They guided the magazine through the period in which it became the largest circulation astronomy publication in the world — larger than the long-established Sky & Telescope; larger than the Japanese leader, Tenmon Gaido. Berry also engineered the creation of an offshoot magazine, Odyssey, aimed at young minds, and the specialized quarterly publication Telescope Making, a significant force in the heyday of the Dobsonian revolution.

When I arrived in 1982, hired by Richard Berry, I brought my magazine, Deep Sky, now re-launched as a quarterly, and joined the Astronomy staff as the most junior of its members. AstroMedia had gone through several rented offices, and by now had its own distinctive stone building near Milwaukee’s lakefront — one that had been a bar prior to a publishing house, complete with mud wrestling matches.

A shared passion for astronomy

The 40 people who worked for AstroMedia consisted of a dozen or so editorial types and many other personnel — the marketing people, circulation gurus, advertising managers, and so forth. The whole place had the feel of an extended family, a kind of loose astronomy club that got together every morning to make a magazine.

Aside from the big hair and the Reagan revolution, the early ’80s were a quiet time in which the AstroMedia crowd excelled at producing and evolving its magazines’ content. At mid-decade, however, lightning struck when Kalmbach Publishing Co., a Milwaukee publisher famous for Model Railroader and Trains magazines, purchased AstroMedia and began publishing the four astronomy titles.

We left our bar building and were absorbed into the Kalmbach life, in another part of town, adjusting to corporate culture as we ramped up for the appearance of Halley’s Comet and lived through the sadness of the Challenger disaster. Former senior editor Rich Talcott, a formidable veteran among the magazine’s history, joined the staff at this time, serving as an engine of creativity until his retirement in 2020. (Talcott remains a frequent contributor to Astronomy magazine to this day.)

With the end of the 1980s came a move to Kalmbach’s new glass-and-steel headquarters in suburbia. Soon thereafter came transition: Richard Berry left the company and Kalmbach discontinued publishing Deep Sky and Telescope Making, and sold Odyssey.

Robert Burnham became the magazine’s editor, and we carried on as Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 slammed into Jupiter, reminding us of Earth’s vulnerability. We featured numerous breathtaking images captured with the newly repaired Hubble Space Telescope, a phenom rescued from failure.

The late 1990s gave us two spectacular comets, Hyakutake and Hale-Bopp, and we debated the potential existence of life on Mars as allegedly captured in a Red Planet meteorite. Astronomy also lost one of its best friends when Carl Sagan died well before his time.

Astronomy magazine enters a new millennium

After holding just about every other job one can have at Astronomy, I became its editor in 2002. In 2003, we relaunched the magazine with a sharper science focus and considerably expanded and improved coverage of the hobby of astronomy, with a special focus on telescopes and observing.

We had a melancholy start of 2003 with the Columbia tragedy; however, we then enjoyed the summer’s wonderful opposition of Mars. And 2004 brought the spectacular rover landings on Mars, two bright springtime comets, and the arrival of the Cassini spacecraft at Saturn. The year 2005 witnessed the Huygens spacecraft landing on Titan, the discovery of a “tenth planet,” and Deep Impact slamming into Comet 9P/Tempel 1.

In 2006 and 2007, exciting events continued apace, with Stardust returning comet material to Earth, WMAP giving us a glimpse of cosmic inflation, arguments over whether or not Pluto was really a planet, and a brief glimpse of Comet McNaught.

The following few years saw more amazing events. We learned that the Andromeda Galaxy and Milky Way will eventually merge. Astronomers discovered enormous numbers of exoplanets. Physicists found the Higgs boson. The supersized rover Curiosity landed on Mars.

The second decade of the new millennium also brought a vast number of astronomical discoveries. We realized, as did astronomy enthusiasts, that we were living in a golden age of scientific discovery. We were now getting answers, or at least getting closer to answers, about some of the longstanding “big questions” about the cosmos. What is its size? Shape? Origin? Eventual fate?

New rounds of rovers explored the surface of Mars in unprecedented detail. New spacecraft gave us a sharper picture of outer solar system planets and moons. The inventory of exoplanets, planets orbiting stars around us in the Milky Way, exploded in numbers. We saw the first evidence of the mergers of black holes and neutron stars, causing warping of space-time, and we captured the first images of the shadows of black holes.

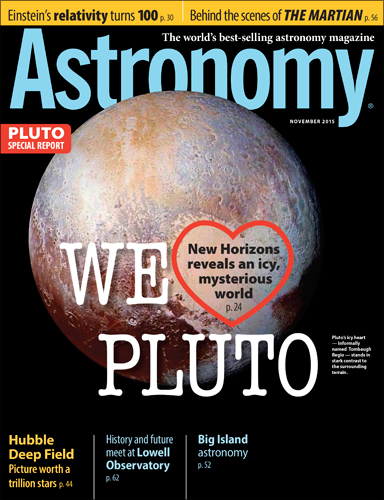

The pace only seemed to quicken. Spacecraft landed on the surface of a comet and gave us an unprecedented look at a strange new world. The New Horizons craft flew past Pluto and we had the final closeup look at the most distant big world in our solar system. Spacecraft also orbited and studied asteroids in close-up fashion. And we saw the beginning of an enormous effort to return humans to the Moon, 50 years after Apollo, and a new public-private partnership in future space exploration.

Full steam ahead

Astronomy magazine is really a story of the people behind it. Dedicated by an obsession with the subject of astronomy, they are driven to assemble the best, most-absorbing material relating to the world of astronomy with every page they have. Names such as Walther, Berry, Maas, and Burnham long ago established the magazine’s stable foundation; the future will expand on this terrific first 50 years.

Names you see in the magazine today will carry on this tradition of excellence. I am honored to work with each of our editors every day. Keep a close eye on their work in the pages of Astronomy; they are the stars of tomorrow. I think Steve Walther would be proud of them. I know that I am.

—David J. Eicher