Some of life’s greatest experiences need no narration. They are stand-alone glories. Rent a houseboat on the Southwest’s Lake Powell, and lose yourself in a random side canyon. A tour guide with knowledge of geology could enhance the experience, but you’ll be in heaven even if no one says a word.

Same with the sky. Even if your Aunt Betty doesn’t know the difference between an asteroid and a hemorrhoid, she’ll still “ooh and aah” at the gibbous Moon through your eyepiece. She doesn’t have to know the big terraced crater is named Copernicus. It’s gorgeous even in anonymity.

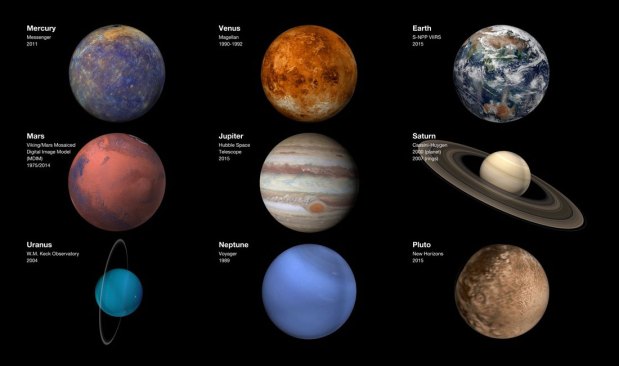

Saturn, its rings displayed better than they’ve appeared for the past nine years, is another winner these nights. You can boost someone’s intellectual enjoyment by mentioning that those rings are so thin relative to their length that they’re analogous to a sheet of paper the size of a city block. But even if you offer your visitor only a soundtrack of silence, they’ll be swept away. Like the Taj Mahal, the apparition alone says it all.

But why do some celestial objects pack a punch while others don’t? In some cases, it’s a matter of visibility. A view of the Milky Way has been absent from city skies for nearly a century. Most people today have never seen it, or perhaps barely so. When vacationing urbanites venture into less populated regions where the Milky Way does manage to appear, it’s still often subtle.

But take these people to truly dark skies, like the Sonoran Desert of the American Southwest, the Chilean Andes, or Egypt’s White Desert. Get them there on a moonless night, preferably between August and October. Now the Milky Way dominates everything. Its mottled structure ambles insanely across the sky like modern art. Its rich detail is so bright that it actually casts shadows. Instantly, you grasp why some early cultures like the Maya regarded it as the night’s focal point. All the discoveries scientists have made about our home galaxy become mere afterthoughts.

In a truly natural setting, the Milky Way dominates the night with an ineffable beauty and powerful presence that ranks it among life’s best visual experiences. Yet it remains a mere concept in today’s light-polluted universe — a textbook item.

THE PERCEPTION OF BEAUTY AND THE HUMAN REACTION TO CELESTIAL OBJECTS ARE RATHER MYSTERIOUS TOPICS.

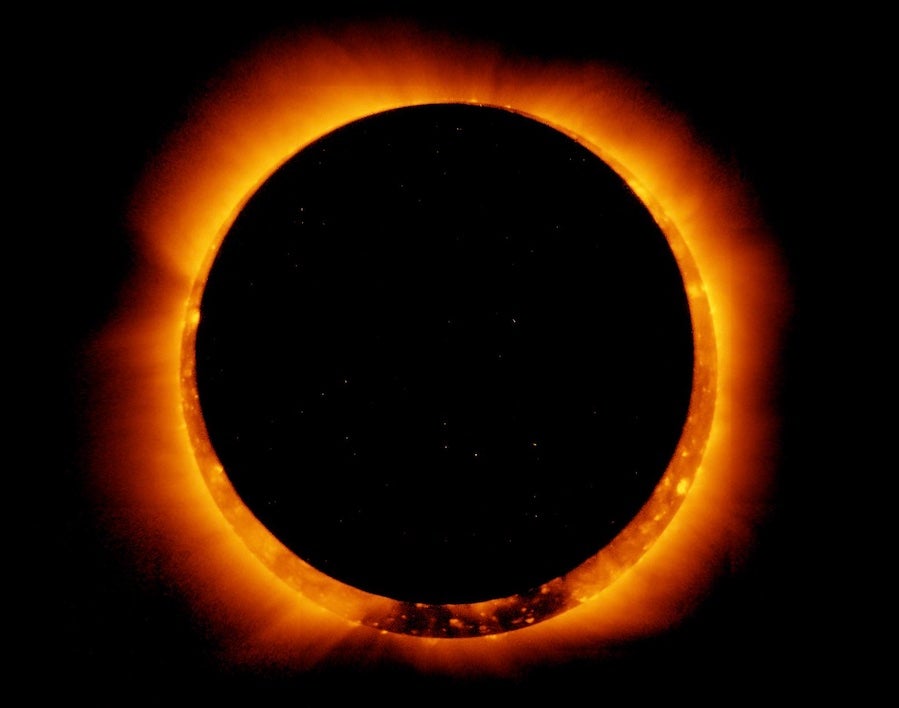

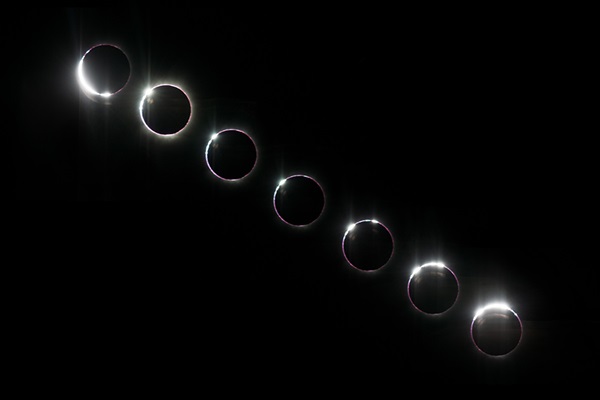

A total solar eclipse provides another case of beauty trumping science. Relatively few have seen one, as such events occur just once every 360 years for any given place on Earth. Most people assume that they are merely another eclipse variety, in the same coolness pool as lunar eclipses or partial solar events, which unfold periodically and are interesting but certainly not life-altering. When an observer raves about her solar totality encounter, relating how animals go nuts and people weep and how it’s the most sacred, soul-touching event of her life, the listener assumes exaggeration is at play. In our ubiquitous camera era, not everyone gets that some things in life must be experienced in person.

But why should the Moon covering the Sun make anyone weep? Why should the rings of Saturn evoke gasps? What is it about these celestial spectacles that so deeply touches the spirit? There’s no logic to it.

This is not to belittle the intellectual side of space. Serious backyard astronomers enjoy the smudgy streaks of spring’s myriad galaxies. When casual visitors see the same thing, however, their reaction is a scientific fascination but rarely a visceral response.

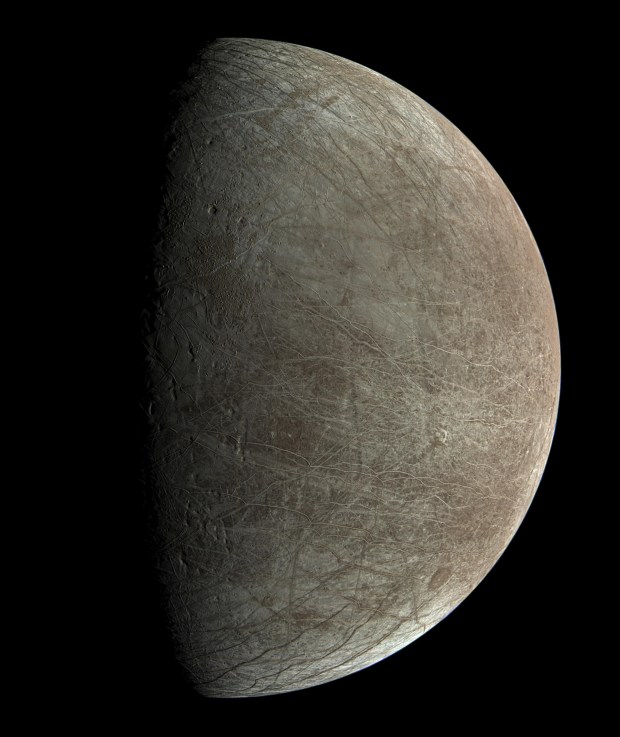

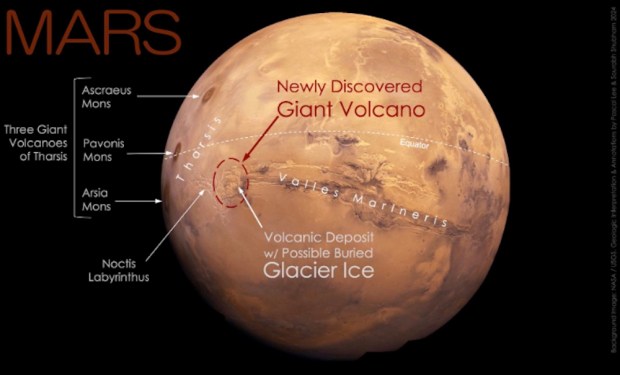

But the problem is not faintness. Brilliant Mars, now at its best of the year, similarly fails to evoke awe at the eyepiece. (Of course, I’m generalizing and also excluding serious astronomers, who basically love everything.)

Here the culprits are familiarity and heightened expectations. Everyone’s seen sharp Hubble Space Telescope images of the Red Planet. Folks are aware of how Mars is “supposed” to look, so your blurry 15-arcsecond-wide wiggly disk cannot compete. By contrast, your guest likely has not heard of M13 — nor even seen a globular cluster — so an 8-inch instrument on a dark May night creates a reliable thrill when pointed toward Hercules. Oddly, a dense star concentration against a black background reliably awakens our sense of awe.

That’s why plain binoculars are sometimes all you need, as with the Pleiades. Other times, the naked eye provides the ticket to glory. Aurorae and great comets always have been trustworthy portals to splendor. With telescopes, only a dozen targets elicit consistent gasps, and if you’ve been at this awhile, you know what they are.

The perception of beauty and the human reaction to celestial objects are rather mysterious topics that lie outside scientific analysis. But by learning where and how they work their magic, you can gain a powerful tool for making new friends for astronomy.

And on a personal greedy level, it’s no small satisfaction to spoon-feed a bit of heaven to your favorite companions. You say, “Open wide!” and give them treats not for their minds, but for an inner place that’s older and more enigmatic.

Contact me about my strange universe by visiting http://skymanbob.com.