Key Takeaways:

- Alnitak, the leftmost star in Orion's belt, is a type O star, characterized by its extreme heat, blue color, and high luminosity (equivalent to 10,000 Suns).

- Alnitak's high mass (28 times that of the Sun) and intense core pressure cause it to consume fuel at an exceptionally rapid rate, losing 200 million tons per second.

- Alnitak's intense ultraviolet radiation, particularly UVC, ionizes atoms and causes mutations, though this is blocked by Earth's ozone layer. Its short lifespan (a few million years) will culminate in a supernova.

- Alnitak's energetic radiation illuminates nearby nebulae, including the Flame Nebula (NGC 2024) and the Horsehead Nebula (Barnard 33), and is embedded within a star cluster near the Orion Nebula (M42).

For once, let’s not seek out the esoteric but do our exploring in one of the night’s most familiar places: the belt of Orion. Its leftmost star, Alnitak (pronounced ALL-nye-tack), is our focus this month.

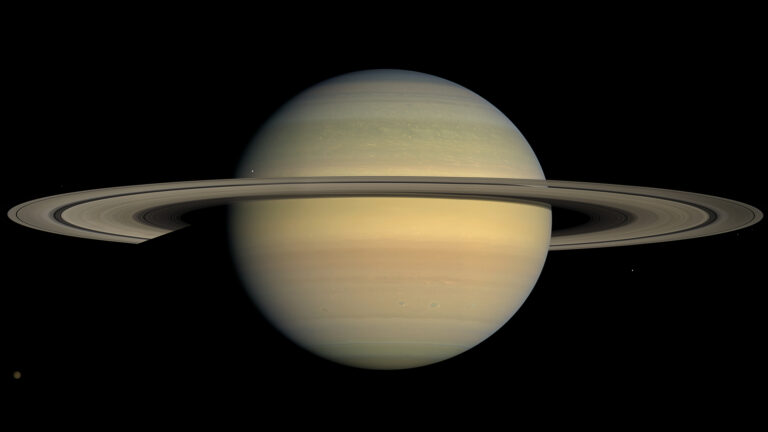

Alnitak is blue because it’s hotter than most stars. And boy, is it hot, shining at visible wavelengths with the light of 10,000 Suns! Can any of us imagine what 10,000 Suns would be like? Most of its energy isn’t even fiercely hot blue light, but instead deadly ultraviolet (UV), the stuff that punishes our beach vanity with a painful sunburn — except that Alnitak’s UV is largely the intense UVC radiation. The miniature wavelengths from UVC ionize atoms and cause worrisome mutations, but Earth’s ozone layer blocks them.

The star is ultrabright, blue, and super hot because it consumes its fuel incredibly fast. Our Sun loses 4 million tons of itself per second, but Alnitak weighs 200 million tons less each second. That’s because its core pressure is super high, and that is because the star is so heavy: Alnitak weighs as much as 28 times more than our Sun, which is the bottom-line explanation for the whole ferocious process.

Such heavy, blue, dazzling stars are classified as type O, and they’re as rare as silent kindergartens. Only 1 star in every 3 million is an O-type star. But Orion has a few all by itself.

Although Alnitak is 20 times wider than the Sun and has dozens of times more mass, its feeding frenzy ensures it won’t live long. Alnitak wasn’t even around when Earth’s first grasses appeared 55 million years ago. In less than a few million years more, it will have used up too much fuel and will expand, change color, and become a red supergiant like Betelgeuse. And it will detonate as a supernova soon thereafter.

That will certainly change the look of Orion’s Belt — a pattern of stars that has always been noticed. (It’s mentioned in the Bible. And in movies like Men in Black.) Zooming back in on Alnitak, the light that rushes out of this star is so energetic that the space around it is a very dangerous place. The Flame Nebula (NGC 2024) almost touches Alnitak’s eastern side, and a narrow streak of glowing gas as long as two Full Moons dangles south of it, illuminated and excited by its UV photons. Halfway along that streak is the famous Horsehead Nebula (Barnard 33).

That celestial chess piece may be the most challenging telescope object of them all. I’ve never seen it in a half-century of observing, even with my dark skies and 121/2-inch f/6 reflector. If, like me, you love cosmic challenges, you’ve probably observed the asteroid Vesta and the planet Uranus with just the naked eye. But the Horsehead? For most, it’s a mythical object that, like love, can be spoken of but not seen. And it would never even be photographed, were it not for the background glow supplied by Alnitak’s energy.

If you have dark conditions, notice all the little faint stars that richly surround Alnitak and the other belt stars. If it’s a moonless rural night, your naked eye is enough to see this nameless star cluster I’m obsessed with mentioning once a decade. Point binoculars at the belt, and this odd grouping in which it’s embedded becomes obvious and rich — even poetically inspiring, since Alnitak and its surrounding stars mark the closest nursery of copious star birth. They, and indeed most of Orion’s stars, are associated with the Orion Nebula (M42) a few degrees lower — the fairyland that reliably thrills lovers of the heavens and which looks red, blue, and purple when photographed, but only green through the eyepiece.

Hot, blue Alnitak is some 800 light-years away. In our own neighborhood, most stars are a mellow yellow or cooler orange, and their radiation is manageable and life-friendly. So, while we have the luxury of enjoying Alnitak from afar, it would be a much different story if it were closer. And it just goes to show that the stupendous and strange can hide within one of the most familiar star patterns in the night sky.