Located on the western edge of Oceanus Procellarum, this trio of craters makes a striking chain one day before Full Moon or two days before New Moon. Lohrmann and Hevelius both are from the Nectarian geological period (3.92 to 3.85 billion years ago) while Cavalerius formed during the Eratosthenian period (3.2 to 1.1 billion years ago). Nearby attractions include the lunar basin Grimaldi just south of Lohrmann, the landing sites of Moon probes Luna 8 and 9 northeast of Cavalerius, and Reiner Gamma, an area of highly concentrated magnetism known as a “bright swirl.”

Lohrmann, at 19 miles (31 kilometers) across, is the smallest of the three. You can observe it, however, through a 4-inch telescope using moderate magnification. Hevelius is the largest with a diameter of 66 miles (106km), so it’s easy to spot the crater’s central mountain and craterlets. If you use a 12-inch scope at 225x, you’ll also be able to observe Rimae Hevelius, a rille system within and to the south of this crater. Finally, Cavalerius is 36 miles (58km) wide with steep terraced walls, a flat floor, and a small central mountain.

To sketch these three craters, focus on rendering highlights along the terminator first and then work outward. Shadows will evolve naturally in your drawing, although you can use a charcoal pencil to accentuate them if needed. You’ll need a white pastel pencil and black paper for this white-on-black sketching technique.

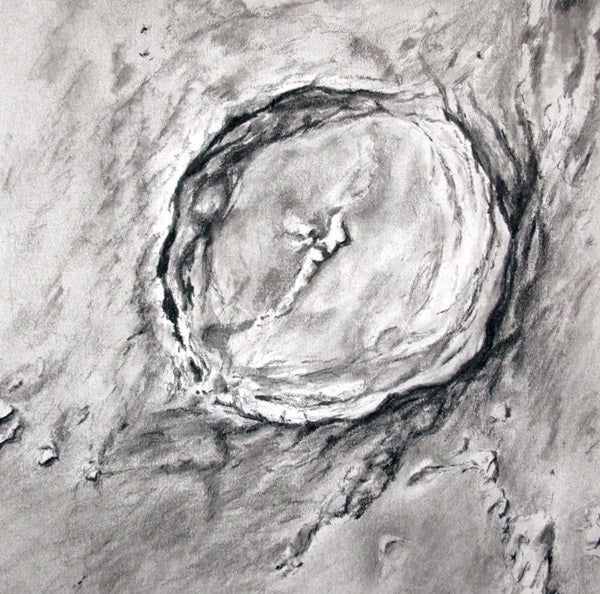

Time is less of a concern when you’re sketching features far from the terminator. Let’s use Eratosthenes Crater as an example. This feature measures 37 miles (60km) across and nestles in the lower arm of Montes Apenninus on the northern edge of Sinus Aestuum. It has a distinct mountain range to the southwest.

Eratosthenes, not surprisingly, formed during the Eratosthenian period when low-lying areas flooded with lava. It appears best one day after either First Quarter or Last Quarter. Pretty much any size telescope will do. As you observe it, increase the magnification to enjoy the details within its tormented walls and elongated central mountain.

The rich tonal range of charcoal on white paper is perfect for detailed sunlit areas, such as the terraced walls of such a complex crater as Eratosthenes. This black-on-white technique is different because you sketch the crater outline and shadows first, followed by the surrounding terrain. Highlighted areas remain untouched.

The Moon has more visible features than any other celestial object. So it’s only fitting, I suppose, that observers have developed several ways to observe — and sketch — its varied terrain. Good luck!