Key Takeaways:

- Jupiter is the largest planet in our solar system, 2.5 times more massive than all other planets combined.

- Jupiter is a gas giant with no solid surface, composed mainly of hydrogen and helium.

- Many spacecraft have explored Jupiter, revealing details about its atmosphere, moons, and magnetic field.

- While very large, Jupiter lacks the mass to become a star.

The brilliant planet Jupiter dazzles anyone with a clear sky. Roman observers named Jupiter after the patron deity of the Roman state following Greek mythology, which associated it with the supreme god, Zeus. But when Galileo turned his telescope skyward in 1610, Jupiter took on new significance. Galileo discovered the planet’s four principal moons — and witnessed the first clear observation of celestial motions centered on a body other than Earth.

Astronomers recognized Jupiter as the largest planet in the solar system long before any spacecraft provided detailed exploration. The planet’s mammoth size — 88,846 miles (142,984 kilometers) at the equator — holds 2.5 times the mass of all the other planets combined. This makes Jupiter the most dominant body in the solar system after the Sun. The planet’s volume is so great that 1,321 Earths could fit inside it.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

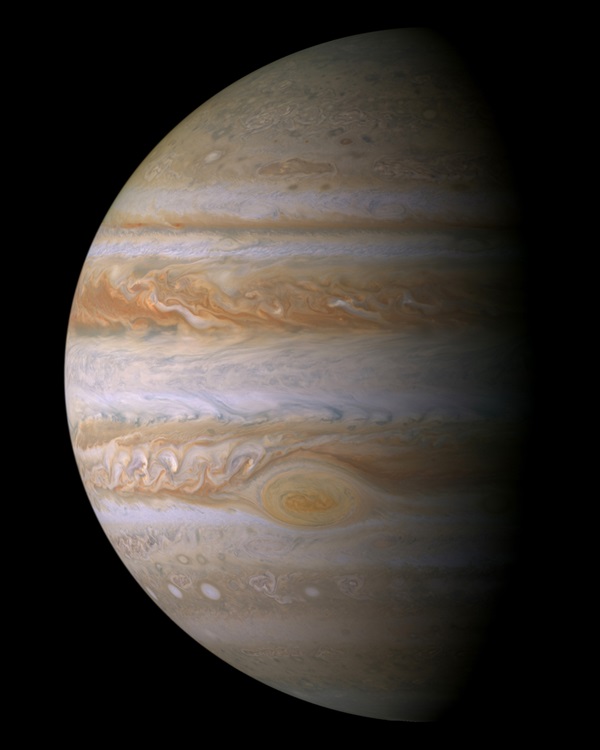

Jupiter is a magnificent example of a gas giant planet. It has no solid surface and is composed of a small rocky core enclosed in a shell of metallic hydrogen, which is surrounded by liquid hydrogen, which, in turn, is blanketed by hydrogen gas. By count of atoms, the atmosphere is about 90 percent hydrogen and 10 percent helium.

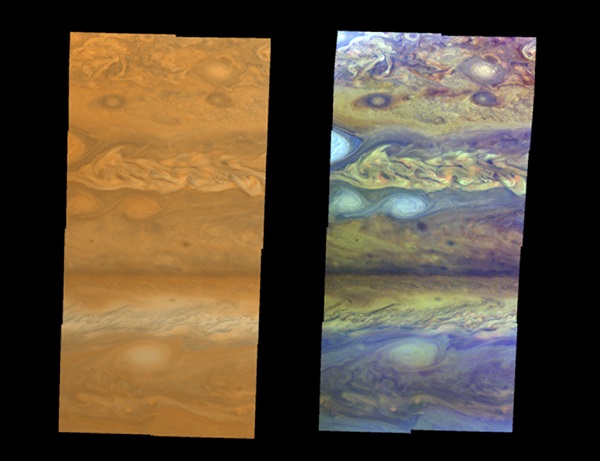

Voyager 1 and 2 increased our jovian knowledge immensely. They mapped the planet’s moons, took detailed images of Jupiter’s complex atmosphere, and even discovered a faint set of rings.

NASA’s Galileo mission, which entered jovian orbit in 1995, gave scientists another windfall. Even as it approached Jupiter in 1994, Galileo witnessed one of the greatest events in solar system history — Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9’s spectacular crash into the giant planet. Galileo sent a probe plummeting into Jupiter’s atmosphere. The probe sampled the atmosphere directly and returned much information before immense pressure deep below Jupiter’s clouds crushed it. In 2003, at mission end, Galileo itself met the same fate.

In July 2016, NASA’s Juno spacecraft entered orbit around Jupiter to begin a new round of scientific observations. With Juno, researchers have precisely mapped Jupiter’s gravitational and magnetic fields, learned a great deal about the planet’s cluster of polar cyclones, and discovered that the gas giant surprisingly rotates like a solid body just below its chaotic cloud tops. Although Juno was initially slated to cease scientific operations in February 2018, the mission was recently extended and is now expected to run through July 2021.

Jupiter’s size and compositional similarity to brown dwarfs and small stars have led some to label it a “failed star.” Had the planet formed with more mass, they claim, Jupiter would have ignited nuclear fusion and the solar system would have been a double-star system. Life might never have evolved on Earth because the temperature would have been too high and its atmospheric characteristics all wrong.

But although Jupiter is large as planets go, it would need to be about 75 times its current mass to ignite nuclear fusion in its core and become a star. Astronomers have found other stars orbited by planets with masses far greater than Jupiter’s.

What about substellar brown dwarfs? Our largest planet still doesn’t come close to these “almost stars.” Astronomers define brown dwarfs as bodies with at least 13 times Jupiter’s mass. At this point, a hydrogen isotope called deuterium can undergo fusion early in a brown dwarf’s life.

So, while Jupiter is a planetary giant, its mass falls far short of the mark for considering it a failed star.