Key Takeaways:

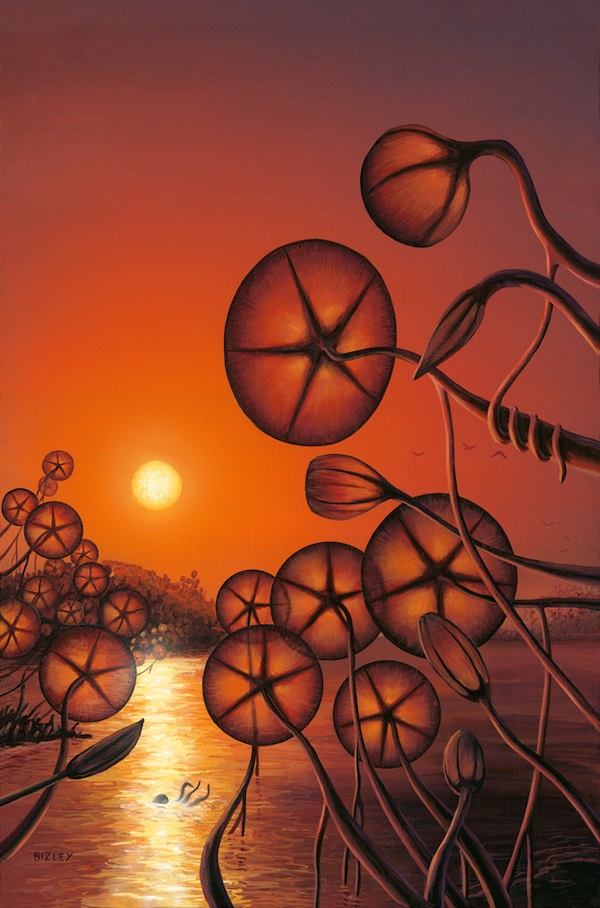

Life on a Tidally-Locked World, Acrylic

In this scene on a tidally locked world, the parent star of the imagined planet never rises or sets. The world’s plants are all seen facing the same direction, competing with each other to reach toward the light. Something is disturbing the waters … possibly an intelligent animal.

The Milky Way and its countless stars, nebulae, and exoplanets were latecomers to space art. The reason is pretty simple: No one knew very much about what lay beyond the limits of our own solar system until the past century or so.

There were depictions of the Milky Way, of course, and the stars and Moon appear in petroglyphs and on seals and decorative objects dating as far back as 1600 B.C. By the 19th century, entire atlases of the sky were being published. They were as scientifically accurate as possible for the time, but often beautifully embellished by imaginative illustrations of the mythologically-inspired constellations.

However, there is a fundamental difference between recording something for science — or even just plain curiosity — and creating a unique work of art because the subject inspires you. It is the difference, say, between an academic treatise on cetology and Moby-Dick. It’s one thing to accurately place a star in its proper position on a chart of the night sky, and another to wonder what that star might look like if you were to visit it or stand on one of its planets.

It wasn’t until 1923 that “spiral nebulae” such as the Andromeda Galaxy were found to be island universes separate from our own galaxy. And until astronomers understood the true nature of stars and the Milky Way, little inspiration existed for artists to paint them.

Probably the first artist to wonder what it might be like to stand under a different star than the Sun was the French artist-astronomer Lucien Rudaux (1874–1947). Like the great American space artist Chesley Bonestell (1888–1986), Rudaux had been a commercial illustrator who developed a serious interest in astronomy. So serious was he that a crater on Mars is named for him, not for his work as a space artist but for his contributions to science.

In the mid-1930s, Rudaux wrote and illustrated a series of astronomy articles for American Weekly magazine. These included “Other Suns With Worlds of Their Own Like Ours?” In this story, nine color paintings depicted scenes on planets orbiting a white dwarf, a red giant, and binary stars; planets within a star cluster; and others. The illustrations speculated not only on the appearance of the stars in the sky, but on how they would affect conditions on the accompanying planets.

Knowing that double stars existed with stars of different colors, Rudaux wondered what visual effects that might produce, and what it might be like to stand on a planet orbiting a binary star system. The result was a simple painting, but the first of its kind. The piece depicted a barren landscape dominated by large rocks casting colored shadows. Rudaux speculated on “the incomparable spectacle of a two-colored moon, created by the light it receives on either side from each of the two suns.”

As astronomers probed ever deeper into our galaxy and learned more about how it came to be and how it functions, every new scrap of knowledge was an inspiration for space artists. Yes, we know what pulsars and black holes are, but how would one look? That is what inspires space artists, and sometimes it’s not an easy question to answer.

I recall an instance when I needed to do an illustration of the Milky Way as it might appear from a planet orbiting a star far outside the galaxy. How bright would it be, I wondered? How might the Milky Way look to the naked eye if we could see the entire galaxy? After all, we live inside it and the band of the Milky Way arching overhead is pretty dim. So, I decided to ask the great astronomer Bart Bok, a leading authority on the Milky Way, who ought to know everything there was to know about our galaxy. “Well,” he said, “you know, I never really thought about that.”

Therein lies, I think, one of the most important contributions space art can make to the science of astronomy. Many astronomers face two limitations in visualizing whatever it is they may be studying. One is that all too often, all that is known about an object is contained in pages of figures and graphs. It can be hard to translate that into something real.

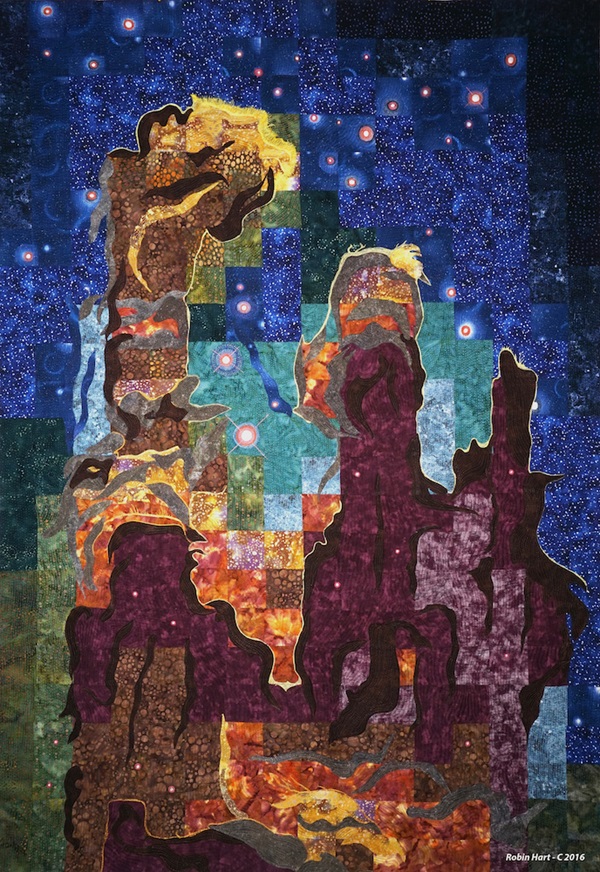

The Pillars of Creation, Fabric

A Hubble deep space photo was the inspiration for this patchwork piece of the Pillars of Creation in the Eagle Nebula. To re-create the stellar nursery, fabrics were applied in a grid pattern (to represent digital data). Applique and intricate threadwork help create the illusion of glowing gases, stars, and dust clouds.

Another is specialization. Focusing on just one narrow area of study can get in the way of visualizing something as a whole. A planetary scientist who is an expert on the climate of Mars may have only a general knowledge of the planet’s geology. The space artist by necessity must draw from every possible source when creating an image, just as a paleontological artist needs to know everything about a dinosaur, from the shape of its teeth to the climate it lived in.

Possibly the most fruitful, and certainly the most exciting, new discoveries for space artists have been exoplanets. Exoplanets have long been a staple of science fiction, from Forbidden Planet’s Altair IV to Star Wars’ Tatooine. Bonestell had assumed that such planets might exist. He created dozens of paintings of stars seen from the landscape of “a hypothetical planet.” But these were the result of aesthetic decisions and not because Bonestell was inspired by any real places.

When the existence of exoplanets was confirmed with the discovery of the first in 1992, whole new vistas opened for space artists. Eventually, a regular menagerie of unusual and outright weird worlds appeared: super-Jupiters and brown dwarfs, planets with ring systems that dwarf Saturn’s, worlds where it rains molten iron, eyeball planets with one frozen and one hot side, ocean and ice worlds, and even planets much like our own — or better.

With every new discovery comes new inspiration for the enthusiastic, curious crowd of space artists.

TRAPPIST-1 Planetary System Viewed From the Surface, Digital

A hypothetical view of the TRAPPIST-1 system, as seen from the surface of one of its numerous planets.

Fireball, Sculpture

Fireball sculptures represent glowing hot meteorites as they explode upon entering Earth’s atmosphere. This example is made of mixed media including iron, bronze, and copper, and is presented on a manzanita branch.

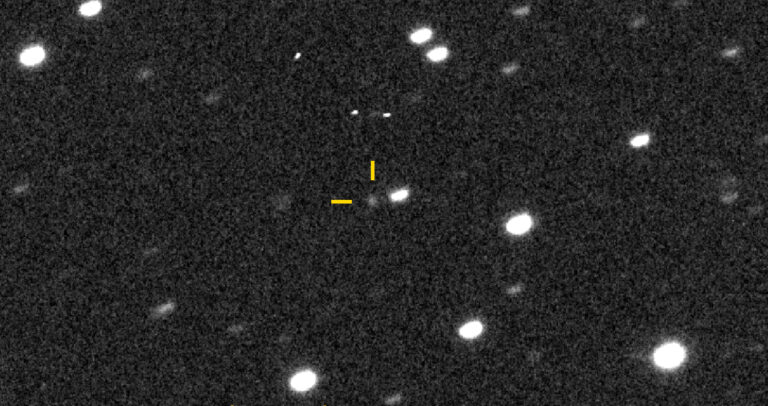

The Rogue, Watercolor/acrylic/digital

We catch a brief glimpse of the hypervelocity star S5–HVS1, the fastest star known, as it flees the galaxy at a rate of nearly 4 million mph (6.4 million km/h).

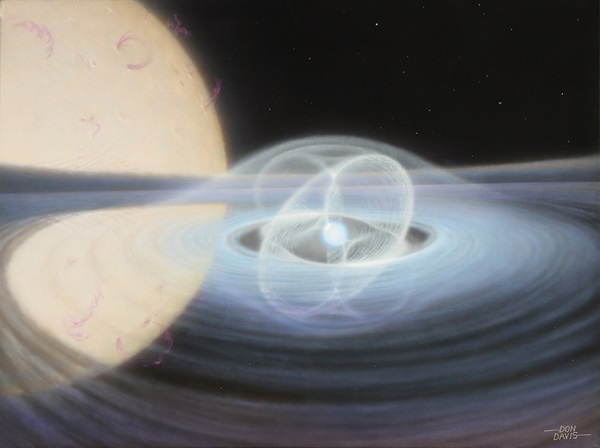

Red and Blue, Oil

Two young binary stars, born from the same cosmic cloud of material but of different mass, temperature, and luminosity, won’t be tangoing for too long. The blue-white star will ultimately collapse into a black hole. Then it will start tearing away the red-orange star’s outer layers, consuming the cooler partner’s material. Asteroids in eccentric orbits — and maybe space tourists passing by while visiting the system — will bear witness to the impending drama.

The Pillars of Creation, Watercolor

The Pillars of Creation became iconic after Hubble’s image of the towering dust clouds was reproduced all around the globe. This artistic take on the Pillars shows us a dramatic look at star formation.