More experienced observers likely will turn their eyes to the morning sky. There, a faint but brightening Comet ISON (C/2012 S1) could approach naked-eye visibility. If it does, this visitor from the solar system’s depths will fuel anticipation of a spectacular show in November and December. But don’t think ISON is the only predawn attraction — Mars and Jupiter both make bold appearances this month.

Our monthly tour of the night sky begins low in the western sky after sunset. Mercury reaches greatest elongation from the Sun on October 9, when it lies 25° east of our star. Unfortunately, the planet doesn’t climb far above the horizon. From mid-northern latitudes, Mercury appears only 3° high in the west-southwest 30 minutes after sunset.

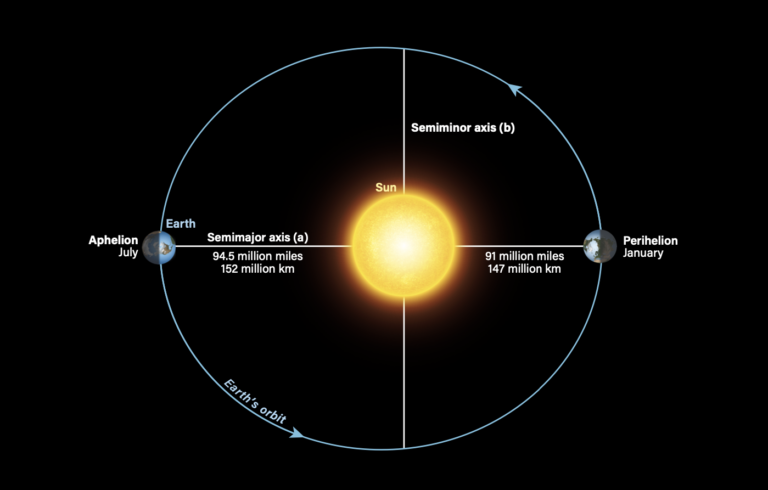

You can blame solar system geometry. In the Northern Hemisphere at this time of year, the ecliptic — the apparent path of the Sun across our sky — makes a shallow angle to the western horizon after sunset. Most of the 25° separation between the Sun and Mercury translates into distance along the horizon and not into altitude. Still, the planet shines brightly (magnitude –0.1) and should show up easily through binoculars if you have an unobstructed horizon.

Mercury doesn’t ply the bright twilight alone this month. Saturn appears 5° north (to the upper right) of the innermost planet October 9 and 10. At magnitude 0.6, the ringed planet will be just as hard to see as its lower but brighter companion.

October 6 provides the best opportunity to view this planetary duo. From North America that evening, a 2-day-old Moon lies in the same vicinity. Mercury appears 2° south (lower left) of the thin crescent while Saturn perches 3° northeast (directly above) of the Moon. Both planets succumb to the Sun’s glare during October’s third week.

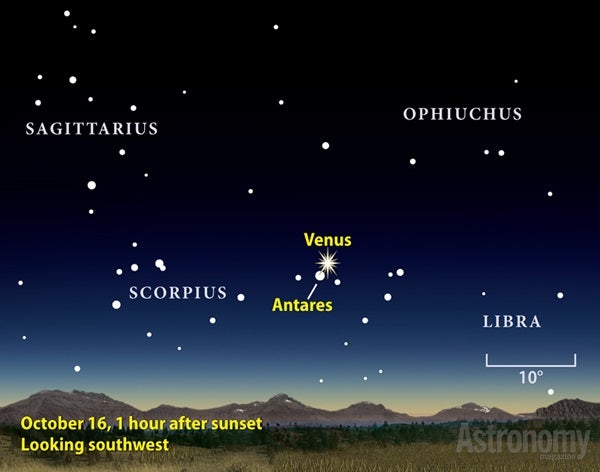

On October 16, Venus passes 1.6° north of Scorpius’ brightest star, 1st-magnitude Antares. At magnitude –4.4, the planet appears more than 100 times brighter than the star. Can you detect the color difference between the two objects? Venus reflects light from the slightly yellowish Sun whereas the red supergiant Antares shines with an orange hue. The pair stands 10° above the horizon 45 minutes after sunset.

You can track Venus’ changing phase through a telescope of any size. On October 1, the planet appears distinctly gibbous, with 63 percent of its disk illuminated. By month’s end, the phase has dwindled to half-lit. The planet’s apparent diameter grows from 18″ to 25″ during the same period.

Once darkness falls, shift your gaze to the opposite part of the sky to hunt for Neptune. The Roman god of the sea spends October wading across the cosmic ocean formed by the background stars of Aquarius the Water-bearer. This constellation appears in the southeast in early evening at midmonth and peaks in the south around 10 p.m. local daylight time.

During October’s first week, you can find Neptune midway between two 5th-magnitude stars: Sigma (σ) and 38 Aquarii. By the 31st, the planet’s slow westward drift has carried it noticeably closer to 38 Aqr.

You’ll need binoculars to see Neptune, which, at magnitude 7.8, glows roughly 10 times fainter than its neighbors. A telescope at high power reveals the planet’s 2.3″-diameter disk and subtle blue-gray color.

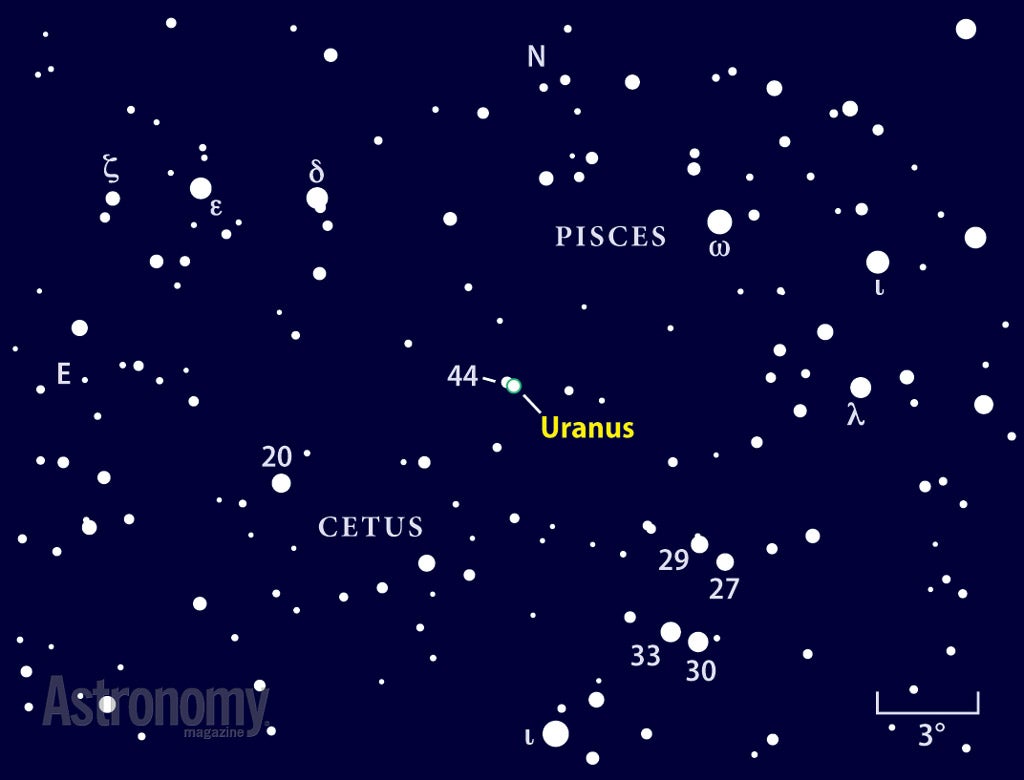

Although Uranus appears bright enough to see with naked eyes from a dark site, binoculars make the job of finding it easier. You’ll need to target a sparse region near the border between Pisces and Cetus. First, find Delta (δ) and Epsilon (ε) Piscium, a pair of 4th-magnitude stars separated by 3.5°. At opposition, Uranus lies 4.8° southwest of Delta. The space between the two grows to 5.7° by month’s end. Point a telescope at the planet to see its distinctly blue-green disk. For more details on observing Uranus, Neptune, and their faint moons, see “Prime time for Neptune and Uranus” in the August Astronomy.

Jupiter rises shortly after midnight local daylight time October 1 and in late evening by midmonth. The strikingly bright object resides high in the southeast by the time twilight commences. The planet appears against the backdrop of Gemini the Twins, a bit less than 10° southwest of that constellation’s brightest star, 1st-magnitude Pollux. At magnitude –2.3, however, Jupiter outshines the star by 25 times. On October 4, the giant planet passes 0.1° due north of magnitude 3.5 Delta Geminorum.

When viewed through a telescope, Jupiter’s disk measures 39″ across the equator and displays a vast wealth of atmospheric detail. Two dark belts, one on either side of a bright equatorial zone, show up through nearly any instrument. On mornings with good seeing conditions, larger scopes reveal a series of alternating belts and zones.

Jupiter’s four bright moons prove equally fascinating. Any telescope will show their elegant dance moves, all choreographed by Kepler’s laws of orbital motion.

Occasionally, these moves produce dramatic changes in a few hours. Target Jupiter the morning of October 10. At around 3 a.m. EDT, Io and Ganymede both appear east of the planet, with Io east of its sibling. The inner moon catches up with Ganymede by 7 a.m. EDT (around dawn on the East Coast), however, and starts to transit the giant world before its neighbor.

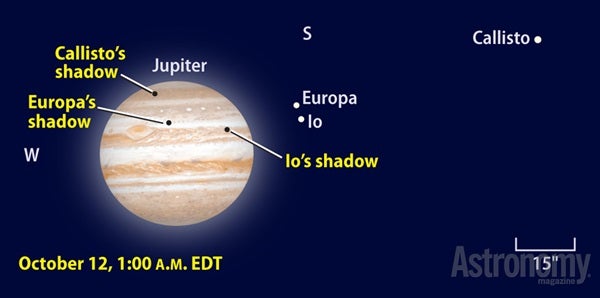

Callisto’s shadow appears on Jupiter’s disk starting at 11:12 p.m. EDT October 11, followed by Europa’s shadow at 11:24 p.m. and then Io’s shadow at 12:32 a.m. All three black dots pock the jovian cloud tops until Callisto’s shadow lifts back into space at 1:37 a.m. Io’s leaves next, at 1:48 a.m., while Europa is the last shadow standing until 2:01 a.m.

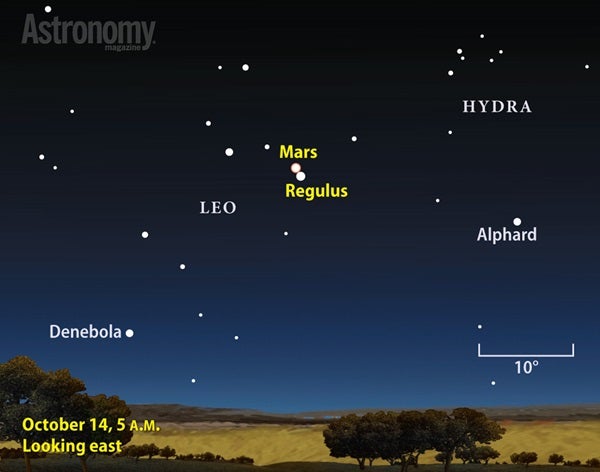

Several hours after Jupiter appears on the scene, Mars pokes above the eastern horizon. The Red Planet rises around 3 a.m. local daylight time October 1 and a half-hour earlier by month’s end. Glowing at magnitude 1.6, Mars appears slightly fainter than nearby Regulus, Leo the Lion’s brightest star. It will be easier to tell the two apart by their colors: The planet appears orange-red while the star has a slight bluish cast.

The eastward motion of Mars relative to the background stars carries it 1° north of Regulus on October 14. By October 31, Mars stands 2° south of M95 and M96, a pair of spiral galaxies in south-central Leo.

But Mars’ most impressive companion has to be Comet ISON (C/2012 S1). The two track together across the morning sky during the first half of October. On the 1st, the comet lies 2° north of Mars; the gap narrows to 1° by the 15th. Astronomers expect ISON to be within the range of small telescopes in early October and binoculars by month’s end. It may even approach naked-eye visibility under the darkest skies.

The comet’s brightness during October will be an important harbinger of things to come. If ISON falls well behind what astronomers are predicting for this month, the projected spectacle in November and December could evaporate as quickly as the ices on its nucleus. (Yes, we know the ices actually sublimate and don’t evaporate.) For complete observing information on this icy visitor, see “Comet ISON brightens before dawn” on p. 50.

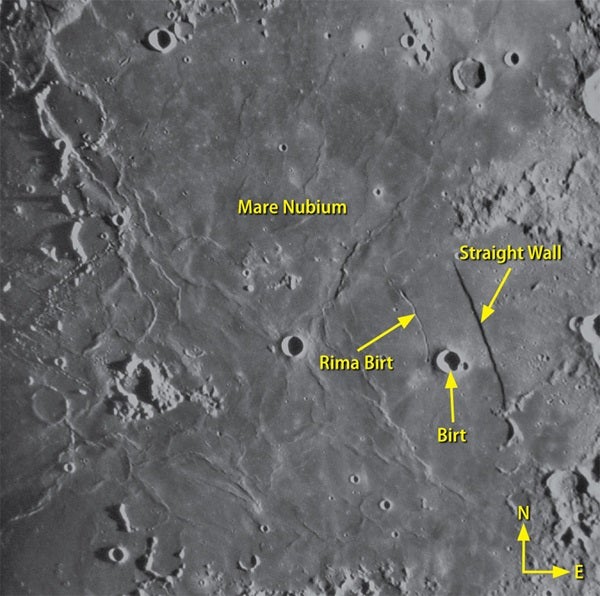

The Straight Wall is the Moon’s best-known scarp. This nearside treasure takes the form of a long black blade that extends outward from its hilt. It lies in the southern third of the Moon and is perfectly placed on a relatively flat lava plain near the eastern shore of Mare Nubium. The Sun rises over this region just after First Quarter phase, on the evening of October 12.

Although its name conjures images of a cliff, the Straight Wall has a slope between 12° and 20° — a decent grade for driving but not steep enough for good tobogganing. Officially labeled as Rupes Recta in many lunar atlases, the Wall stretches about 70 miles long and rises some 1,300 feet above the plain. The scarp likely formed at the end of the period when lava flooded Mare Nubium, when the terrain sank and pulled westward away from the older terrain to the east. You’ll see Mare Nubium better the following evening (October 13), once the Sun climbs higher in the lunar sky. By then, however, the shadows that make the Wall stand out will be gone.

The length of the shadows on the 12th, longer than those in the photo at right, should bring Rima Birt into view. This intriguing wormlike channel extends north from the 11-mile-wide crater Birt. To best see this groove, use high power and practice patience.

Traditionally, the Orionid meteor shower ranks as October’s top display. But this year, the shower peaks October 21, when a gibbous Moon shares the predawn sky. Its presence washes out fainter meteors and diminishes the impact of brighter ones.

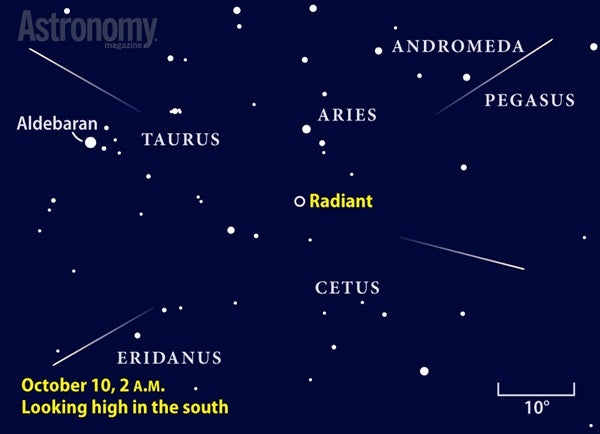

But October offers another shower, called the Southern Taurids, which peaks before dawn on the 10th. The crescent Moon sets the previous evening. The radiant — the point from where the meteors appear to emanate — climbs highest in the south around 2 a.m., when observers can expect to see up to 5 meteors per hour.

This radiant traverses an area of sky roughly 20° by 10° and, despite the shower’s name, lies in the northern part of Cetus at the time of the peak. Southern Taurid meteors tend to be bright and move more slowly than typical meteors, which make them good subjects for imaging as well as naked-eye viewing.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS |

||

| Evening Sky |

Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Mercury (southwest) |

Jupiter (northeast) |

Mars (east) |

| Venus (southwest) |

Uranus (south) |

Jupiter (southeast) |

| Saturn (west) |

Neptune (southwest) |

Uranus (west) |

| Uranus (east) | |

|

| Neptune (southeast) | |

|

The comet we’ve been waiting a year for is finally nearing its peak. Although our best views of ISON (C/2012 S1) will come in November and December, October should see it brighten to within the range of small telescopes and binoculars under a dark sky by month’s end. ISON lies in the east before dawn, where its path glides almost parallel to bright Mars. Avoid observing from sites east of a city so you won’t have to look through a veil of light pollution.

Any scope at low power should show that ISON is not a galaxy. Compare and contrast it with the nearby spirals M95 and M96. (The comet passes just south of this pair October 25.) Can you see ISON grow brighter week by week, as it should?

At medium magnification, notice how the galaxies have a mildly elliptical shape. Each shows a nearly pointlike core surrounded by a dimmer inner region wrapped in a halo that fades out quite uniformly. ISON’s light drops off, too, but in a much different way. The comet’s interaction with the solar wind and radiation compresses the eastern side into a fairly sharp boundary while the western flank appears noticeably more diffuse. Earth’s current position gives us a view of the comet halfway between edge-on and broadside, which means that the northern edge should appear sharp.

Now push the power up to 150x or more, and look for details in the comet’s core. Its true surface — the “dirty snowball” that creates the whole show — lies hidden beneath layers of dust. The nearly point source that glows brightly in the middle of the comet’s head is the so-called false nucleus. Also look for any elongation or uneven shading in the core. It might be a month early for ISON to display these characteristics, but it doesn’t hurt to look.

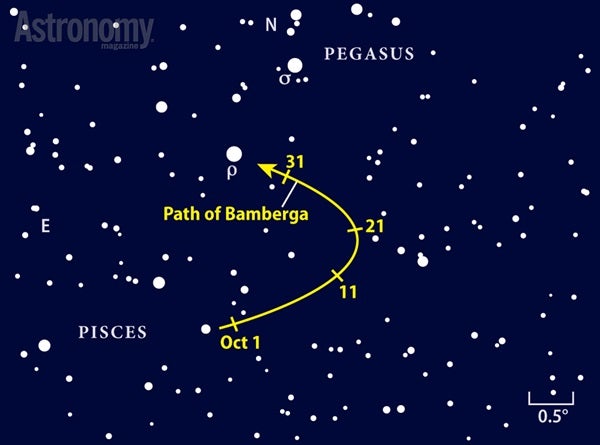

Competitive stargazing may not be common, but most amateur astronomers enjoy making observing lists and chalking up records of unusual sights. October offers you a chance to bag one of the latter: the high-numbered asteroid 324 Bamberga. Because the numbers reflect their order of discovery, and astronomers typically find bright objects before dim ones, we rarely feature asteroids with numbers greater than 30.

Start your search at the Great Square of Pegasus, which lies more than halfway up in the southeast at mid-evening. Imagine the Square as a giant clock with the lower right corner at the center and the upper right corner marking the big hand at 12. Our guide star for Bamberga is 5th-magnitude Rho (ρ) Pegasi, which lies where the small hand would point to 5 o’clock. The asteroid remains within 2° of Rho all month.

Few background stars here glow as bright as the magnitude 8.5 asteroid, so you should be able to identify the dot. Return to the same region another night to confirm that the object has moved and thus is the asteroid. Austrian astronomer Johann Palisa used this systematic approach to discover Bamberga in 1892.

Bamberga orbits on a highly elongated path — only six of the first 500 asteroids have orbits that deviate more from a circle. Although it completes a circuit of the Sun every 4.4 years, the geometry delivers a close approach to Earth only every fifth cycle. So, we likely won’t be featuring Bamberga again until 2035.

Martin Ratcliffe provides planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. from his home in Wichita, Kansas. Meteorologist Alister Ling works for Environment Canada in Edmonton, Alberta.