It’s a busy month in Earth’s sky. At the top of everyone’s mind is Comet ISON (C/2012 S1), which could be magnificent both after dusk and before dawn. But don’t pass on the many bright planets visible these long nights. Venus outshines every object except the Sun and Moon, making it impossible to miss on December evenings. Jupiter gleams almost all night as it approaches its peak in early January. And mornings favorably show off Mercury, Mars, and Saturn.

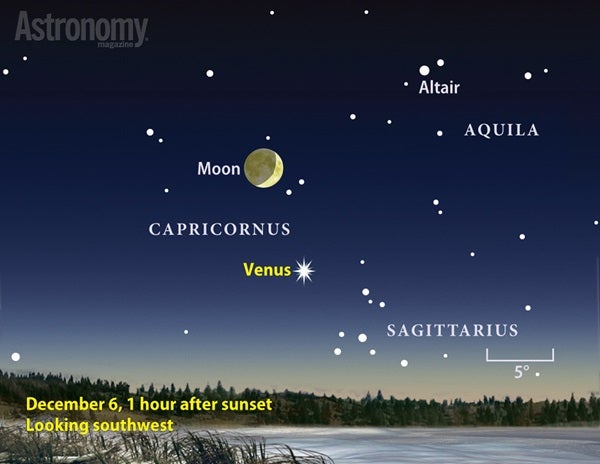

Venus commands your attention as darkness falls. It shines at magnitude –4.9 — the brightest it ever gets — throughout December’s first half. (Greatest brilliancy occurs officially on the 6th, but you won’t notice any brightness change until after midmonth.) If you have a carpet of fresh snow, wave your hand a foot or so above the ground under a dark sky, and you should see the planet casting a shadow. Venus fades to a still impressive magnitude –4.5 by month’s end.

This world also lies highest in the southwestern sky in early December. It stands 15° above the horizon an hour after the Sun goes down and doesn’t set until nearly two hours later. A waxing crescent Moon passes 8° north of Venus on December 5. By the 31st, the planet lies just 4° high an hour after sunset.

Any telescope shows the remarkable changes Venus undergoes. On December 1, the planet appears 37″ across and 31 percent lit. New Year’s Eve reveals a 59″-diameter disk, but the Sun illuminates only 5 percent of it.

You’ll have to wait for twilight to fade completely before hunting for Uranus and Neptune through binoculars. Look for Neptune around 7 p.m. local time, when it lies 30° high in the southwest. First find Theta (θ) and Iota (ι) Aquarii, a pair of 4th-magnitude stars near Aquarius’ border with Capricornus. With 7×50 binoculars, place Iota at the bottom of your field of view; Theta will appear at the top right. Then locate 5th-magnitude 38 Aqr, the brightest star on the line joining these two.

Neptune lies about 2° northeast of 38 but appears 10 times fainter, at magnitude 7.9. The handful of 7th- and 8th-magnitude stars that dot this area will complicate your search. To confirm a sighting, target the object with a telescope at high power and look for a blue-gray disk measuring 2.3″ across.

Uranus stands more than halfway to the zenith in the southern sky after darkness settles in. It’s easier to locate than Neptune because it shines at magnitude 5.8, more than two magnitudes brighter than its planetary sibling. Uranus rests on the Pisces-Cetus border, so use 4th-magnitude Delta (δ) Piscium as a guide star. The planet lies 6° southwest of Delta, or slightly less than the field of view in 7×50 binoculars.

As with Neptune, a telescope provides proof that you’re viewing a planet. At medium magnification, you’ll quickly recognize Uranus’ distinctive blue-green hue and see its 3.6″-diameter disk.

Giant Jupiter rises shortly after 7 p.m. local time December 1 and around sunset on the 31st, when it remains visible all night. With opposition and peak visibility arriving during January’s first week, the gas giant appears stunning this month. It shines at magnitude –2.7 New Year’s Eve, when it dominates the sky after Venus sets.

Jupiter lies against the backdrop of Gemini, approximately 10° southwest of that constellation’s brightest stars, Castor and Pollux. It resides much closer to magnitude 3.5 Delta Geminorum, however. On December 10, the planet skims just 15′ — half the Full Moon’s diameter — north of the star.

You’ll want to spend a lot of time at the telescope viewing details in Jupiter’s atmosphere. The planet is almost perfectly placed for late-evening and after-midnight viewing during December. It climbs higher than 60° for more than three hours every night. The great altitude means you don’t have to look through as much of Earth’s image-distorting atmosphere.

The planet’s feature-laden disk grows from 45″ to 47″ across this month. At first glance, you’ll see two dark stripes, one on either side of the planet’s brighter equator. These two belts initially may appear featureless, but close inspection reveals subtle dark spots and turbulent edges. These features move quickly in response to Jupiter’s rapid spin — it completes a rotation once every 10 hours or so.

The four Galilean moons of Jupiter — Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto — orbit the planet in 1.8, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. They change relative positions from night to night and often from hour to hour. Observers particularly enjoy watching when a moon passes in front of, or transits, the planet’s disk shortly after its shadow transits the jovian cloud tops.

With the long December nights and Jupiter’s near-optimal position, plenty of satellite events take place this month. But perhaps the most interesting sequence occurs December 17/18 and involves Callisto and Io. The pitch-black shadow of Callisto, which shows up easily through even small telescopes, starts to transit Jupiter’s disk at 10:04 p.m. EST. The dark dot takes more than three hours to cross the planet’s southern hemisphere.

As the shadow exits the disk at 1:17 a.m. EST, the moon itself appears 8″ off Jupiter’s southeastern limb. The gap closes quickly, however, and by 2:20 a.m. EST the moon begins its own transit. This journey doesn’t conclude until 5:46 a.m. EST.

Some 20 minutes before Callisto reaches the planet’s southwestern limb, Io’s shadow begins a transit on the opposite side, at 5:27 a.m. EST. Nearly 30 minutes later, Io commences its own transit. Although observers on North America’s East Coast will have to watch the moon and its shadow march in lock step across the cloud tops during twilight, West Coast viewers will see it in a dark sky.

Although Mars hasn’t offered amateur astronomers much all year, that’s starting to change. The Red Planet rises around 1 a.m. local time in early December and an hour earlier by month’s end. During this period, Mars brightens from magnitude 1.2 to 0.9, the brightest it has been since 2012.

Earth’s neighbor passes several modest stars in the constellation Virgo during December. On the 2nd, Mars treks just 1.2° north of magnitude 3.6 Beta (β) Virginis. On the 17th, the planet slides 0.7° north of magnitude 3.9 Eta (η) Vir, and it stands a similar distance south of magnitude 2.7 Gamma (γ) Vir on the 29th.

Although the ruddy world looks nice with naked eyes and binoculars, the telescopic view still leaves something to be desired. Even by month’s end, Mars spans only 7″ and shows few details beyond its white north polar cap. The planet grows significantly larger in early 2014, however, and should show many dusky surface markings.

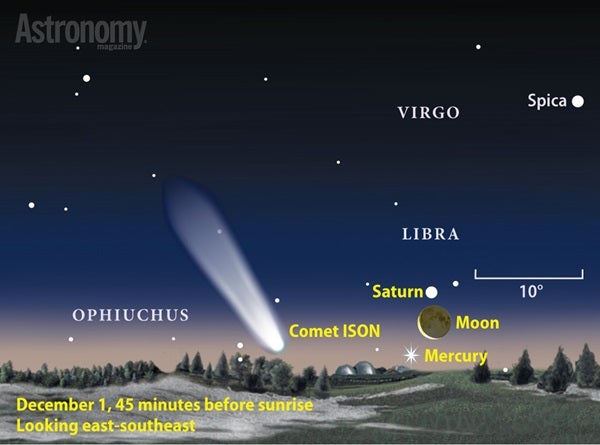

December’s first morning promises a fine sight. A slender crescent Moon rises around the beginning of twilight and climbs nearly 10° high in the southeast by 45 minutes before sunrise. Mercury, which shines at magnitude –0.6, lies 5° east of the Moon while Saturn (magnitude 0.6) appears 2° above our satellite.

Binoculars will provide the best views of this scene and should reveal a bonus object: Comet ISON. Assuming that this long-awaited visitor survived its brush with the Sun in late November, ISON will quickly improve before dawn. Although the comet’s nucleus lies on the horizon 45 minutes before sunup on the 1st, the tail angles above the horizon and ought to be easier to see. If predictions hold, ISON should shine at 1st magnitude this morning.

Of the four morning objects on display December 1, the Moon disappears first. It succumbs to the Sun’s glow the next day when it reaches its New phase. Mercury exits from the stage next. Just a week into December, the innermost planet sits only 4° high 30 minutes before sunrise. It becomes lost in the dawn glow a few days later.

Saturn fares much better. By the end of the year, it rises four hours before the Sun and appears 20° high in the southeast as twilight begins. Any telescope shows the planet’s 16″-diameter disk and beautiful ring system, which spans 36″ and tilts 22° to our line of sight.

But Comet ISON likely will draw the lion’s share of attention. The comet tracks northward rapidly and climbs higher into a darker morning sky. Still, astronomers expect it to dim by five magnitudes this month, so the best views should come during December’s first two weeks. For more details on viewing this cosmic visitor, see “Comet ISON’s dazzling all-night show” on p. 56.

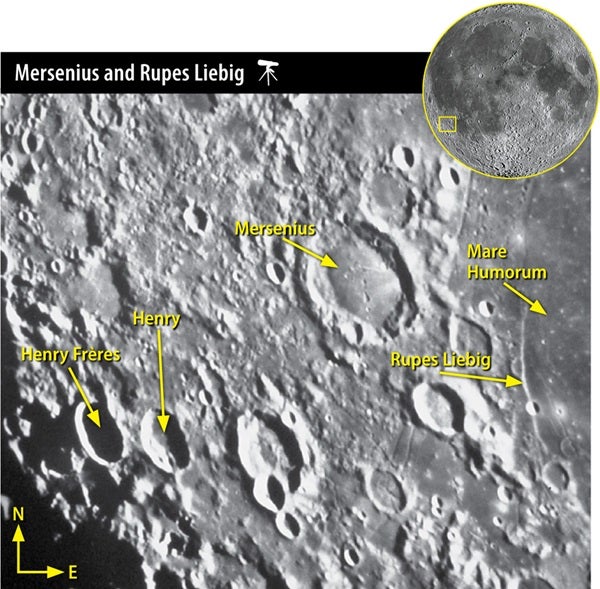

A CACOPHONY OF CRATERS AND CLIFFS

The evening of December 13 features a waxing gibbous Moon. While meteor observers wait for the bright light to set and clear the stage for Geminid viewing, Moon watchers will break out their telescopes and target the lunar southwest. Tucked along the western shores of Mare Humorum (Sea of Moisture) lies a curving scarp (or cliff) named Rupes Liebig. Centered on the impact that created the basin, the cliff appears as a white arc that changes by the hour as it catches the rising Sun. The scarp formed when Humorum sank under the weight of lava, cracking the floor and causing it to fall. A smaller impactor later punctuated the scarp with a diminutive crater.

Notice a few line segments on Rupes Liebig’s western side. They belong to a family of rilles on the lunar nearside that appear radial to a huge but now buried basin. The ancient impact that excavated this basin also created deep cracks. Later on, the walls slumped and impacts splashed material into them.

On the 14th, sunlight fully illuminates the modestly battered crater Mersenius. This 52-mile-wide crater should have a central peak, just like the similarly sized Tycho. It’s there, but it’s buried under lava that oozed through cracks in the floor. Scientists don’t know why the lava pushed upward in a broad dome instead of forming a flat pool. This bulge shows up best on the 13th when the Sun hangs low.

Can you see a dragon’s mouth tucked south of the pair of Henry craters? The play of light and shadows on peaks and crater rims there led observer Dave Gamble to imagine “a mouthful of very bright teeth.”

Similar conditions return between midnight and 3 a.m. EST December 15. They are nothing more than tricks of the terrain and the mind’s fancy, but it’s fun to observe them, especially when the illusion may come and go in a half-hour.

A MOON-FLECKED GEM

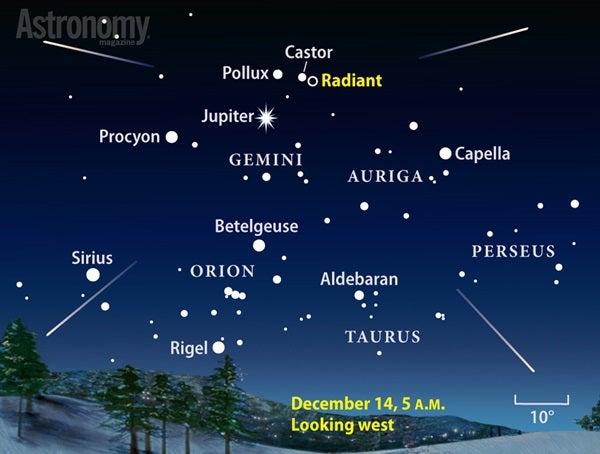

Moonlight affects the Geminid meteor shower this year, but it won’t wash the shower away. The Geminids peak the night of December 13/14, when a waxing gibbous Moon lights up the sky until it sets after 4 a.m. local time. Twilight starts about an hour later, giving observers a brief window.

The radiant, the point from which the meteors seem to emanate, then lies about halfway up in the western sky. This likely will cut the number of meteors you can expect to see by at least half from the theoretical maximum of about 120 per hour. Even so, this leaves the 2013 Geminids among the best of the year.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS |

||

| Evening Sky |

Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Venus (southwest) |

Jupiter (southeast) |

Mercury (southeast) |

| Uranus (southeast) |

Uranus (west) |

Mars (south) |

| Neptune (south) |

Jupiter (west) |

|

| Saturn (southeast) |

||

ISON MAKES A BEELINE TO THE NORTH

Greatness is fleeting. Comet ISON (C/2012 S1) will max out for just a week or so in late November and early December. Before and after this peak, most astronomers expect ISON to look like Comet PANSTARRS (C/2011 L4) did in March and April — a nice object for experienced observers but not as much for the general public.

You’ll need to be up by the crack of dawn to catch ISON’s tail above the eastern horizon before the rest of the comet climbs into view, followed too quickly by the Sun itself. Use binoculars and a telescope at a range of magnifications to see the most cometary detail.

As ISON retreats from the Sun’s radiation, its brightness and activity level will diminish, but its contrast against the darker background sky will surge. To naked eyes or through binoculars, the prettiest views may come a week or more into December.

No matter how much the comet flares or fizzles, it always will look better from under a dark sky. Search for an observing site east of your city or town to put the veil of light pollution behind you. But even if you must remain in town, observe at every opportunity — any night could provide the observation of a lifetime.

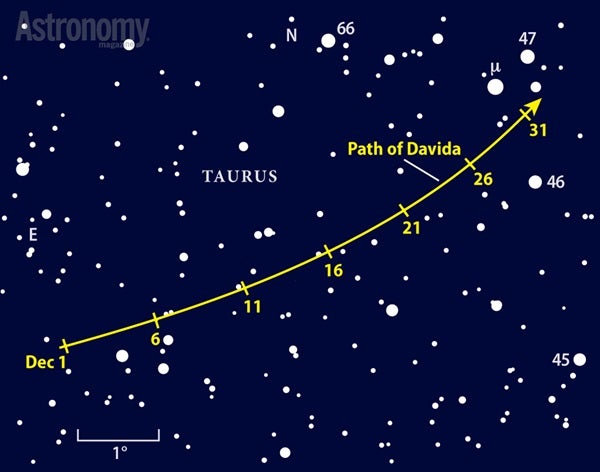

LOWLY DAVIDA RUNS WITH THE BULL

What’s the highest numbered asteroid you’ve ever seen? You could achieve a personal best this month with 511 Davida, whose elliptical orbit brings it about as close to Earth as it can get. This favorable alignment occurs only every 45 years.

Astronomers estimate that Davida spans a respectable 200 miles and ranks among the 10 most massive members of the main asteroid belt. American astronomer Raymond Dugan discovered the object photographically in 1903.

Despite the object’s high number, Davida peaks at 10th magnitude this month and shouldn’t be difficult to hunt down. Wait until mid-evening for Taurus to climb high. The asteroid lies in the southern part of this constellation, roughly 10° south of Aldebaran. The background sky has a nice range of star brightnesses to provide you with a recognizable pattern at the eyepiece. Magnitude 4.3 Mu (μ) Tauri serves as an anchor point near the end of Davida’s track.

If you want to see a solar system object move in just two or three hours, the evening of December 7 will work well. Davida then slides past two 9th-magnitude stars. The three form a triangle whose shape changes noticeably in a couple of hours. You need to draw only three dots on a sheet of paper and return to identify the one that shifted position.

Martin Ratcliffe provides planetarium development for Sky-Skan, Inc. from his home in Wichita, Kansas. Meteorologist Alister Ling works for Environment Canada in Edmonton, Alberta.