October nights bring long hours of dark skies punctuated by wandering planets, streaking meteors, and an exceptional occultation. Venus brightens the evening sky along with Mars and Saturn, while early risers get treated to views of Mercury and Jupiter. Uranus bridges the gap between evening and morning as it shines at its best all night long. For viewers who prefer more ephemeral events, the Orionid meteor shower lights up the predawn sky on the 21st and the Moon passes through the Hyades star cluster — and directly in front of Aldebaran — the night of October 18/19.

Planet watchers can start their night soon after sundown, when Venus appears low in the southwest. The “evening star” shines at magnitude –3.9 and jumps out of the bright twilight. The planet stands nearly 10° above the horizon a half-hour after sunset. A slender waxing crescent Moon passes 5° above Venus on October 3.

The view of Venus through a telescope doesn’t change much during October. On the 1st, its disk spans 12″ and appears 85 percent lit. By month’s end, the planet measures 14″ across and the Sun illuminates 78 percent of its Earth-facing hemisphere.

Venus calls three constellations home during October. It spends the first half of the month among the background stars of Libra. It then crosses into Scorpius on the 17th and Ophiuchus on the 24th. And on the 25th, the brilliant world stands 3° due north of Scorpius’ orange-red luminary, 1st-magnitude Antares.

That same evening, Saturn lies 5° east-northeast of Venus. The inner planet’s eastward motion relative to the background stars carries it 3° south of the ringed planet the evenings of October 29 and 30. Look for magnitude 0.5 Saturn to the upper right of Venus.

Saturn doesn’t look as spectacular through a telescope this month as it did during the spring and summer. Its lower altitude means that we view it through more of the distorting effects of our planet’s atmospheric turbulence, resulting in poor “seeing.” Still, the view is worth the effort. Saturn’s disk measures 16″ across in mid-October while the rings span 35″ and tilt 26° to our line of sight. The dark Cassini Division that separates the outer A ring from the brighter B ring should appear conspicuous in decent seeing.

You also should see several of Saturn’s satellites. The brightest, 8th-magnitude Titan, shows up easily through any scope. It orbits the planet in 16 days and slides due south of Saturn on October 2 and 18 and north of the planet on October 11 and 27. The ringed world’s three 10th-magnitude moons — Tethys, Dione, and Rhea — are a bit harder to see with the planet so low. Still, a 4-inch instrument with good optics should pick them up on most evenings.

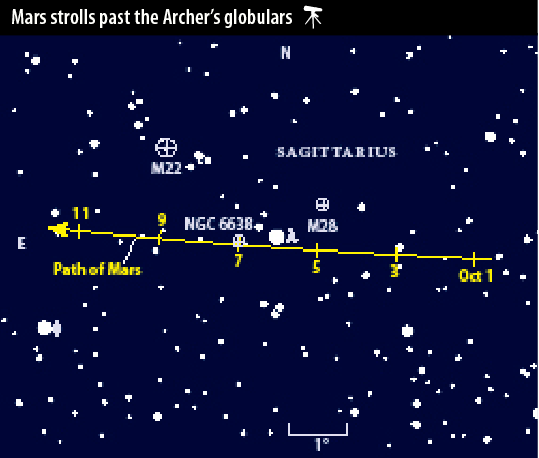

As Venus and Saturn dip toward the horizon, shift your focus up to Mars. The Red Planet lies among the rich star fields of Sagittarius. In early October, the magnitude 0.1 world is a magnificent sight posed against a stunning backdrop. On the 1st, it lies in the same binocular field as the Lagoon Nebula (M8), which stands 2.5° to the northwest.

The planet moves 0.8° south of 7th-magnitude globular cluster M28 on October 5. Lambda (λ) Sagittarii, the 3rd-magnitude red giant star that marks the top of Sagittarius’ Teapot asterism, resides in the same low-power telescopic field. The next evening, Mars passes 0.2° south of this star.

The planet skims 4′ south of the 9th-magnitude globular NGC 6638 on October 7. Mars rounds out its encounters with globulars on the 9th, when it appears 1.6° south of 5th-magnitude M22. You’ll want to view these vistas soon after the sky darkens while Sagittarius is still reasonably high.

The Red Planet stands out this month largely for the company it keeps. Its disk measures only 8″ across and won’t show the surface features it did a few months ago. You’ll likely need an 8-inch or larger scope with fine optics and good seeing conditions to spot any appreciable details.

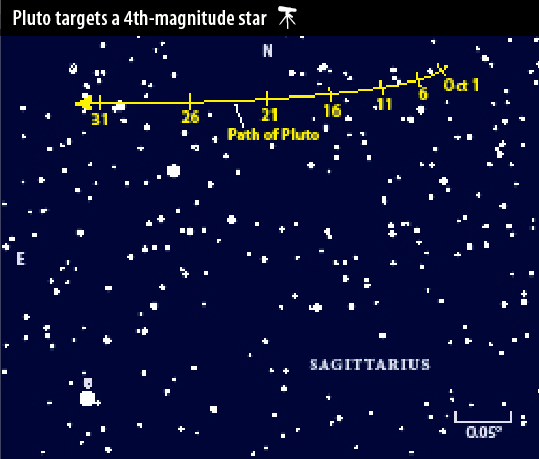

Sagittarius holds one other solar system world within reach of an 8-inch instrument under excellent conditions. Pluto normally would be a bear to track down against the Archer’s rich backdrop, but its proximity to magnitude 3.8 Omicron (ο) Sgr in northeastern Sagittarius makes the task a little easier. During October’s final week, Pluto lies 0.3° north and a touch west of Omicron. The dwarf planet passes 4′ due north of a 7th-magnitude field star on the 27th and just 8″ north of a 9th-magnitude star on the 30th. At magnitude 14.2, Pluto glows 100 times dimmer than the latter star. Use the finder chart on the opposite page to home in on the world.

Neptune resides among the background stars of Aquarius, which lies due south and at its highest in midevening. Glowing at magnitude 7.8, the eighth planet shows up quite easily through tripod-mounted 7×50 binoculars. Neptune begins October 2° southwest of 4th-magnitude Lambda Aquarii and slowly drifts away. By the month’s final week, it lies 2.5° from Lambda and just 0.1° north of a pair of 9th-magnitude stars. A telescope reveals Neptune’s 2.3″-diameter disk and subtle blue-gray color.

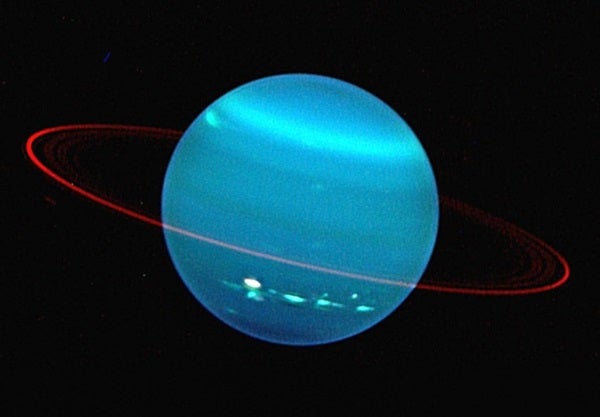

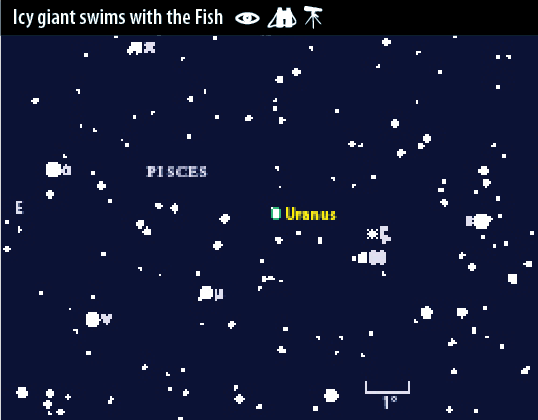

Shift your gaze one constellation east of Aquarius, to Pisces the Fish, and you’ll be staring at the current home of Uranus. This ice giant world reaches opposition and peak visibility on October 15, though the view hardly suffers during the rest of the month. The planet glows at magnitude 5.7 throughout October, which makes it bright enough to glimpse with the naked eye from under a dark sky.

Uranus climbs above 30° by 9 p.m. local daylight time in mid-October. To track it down, first find autumn’s most conspicuous star pattern, the Great Square of Pegasus. From magnitude 2.8 Algenib (Gamma [γ] Pegasi), the square’s southeastern corner, scan 12° southeast to find the 4th-magnitude suns Delta (δ) and Epsilon (ε) Piscium. Using binoculars, then look a few degrees east and south to locate 5th-magnitude Zeta (ζ) and Mu (μ) Psc. At opposition, Uranus lies midway between and a bit north of a line joining these two stars. A handful of stars occupies this region, but all glow fainter than the planet.

Once you find Uranus, put the binoculars aside and see if you can spot it with your naked eye. To confirm a planet sighting, point your telescope at the target. Only Uranus shows a disk, which measures 3.7″ across and has a distinctive blue-green color.

Dawn’s approach brings two more planets into view. Mercury reached greatest elongation in late September but continues to brighten in early October. On the 1st, the magnitude –0.8 planet rises 90 minutes before the Sun and climbs 10° high in the east a half-hour before sunup.

Although Jupiter is invisible on the 1st, it quickly pops into view. By the 10th, the giant planet appears 1.6° below Mercury. The next morning, they appear side by side and just 0.8° apart. Jupiter lies to the right and shines a bit brighter, at magnitude –1.7, than magnitude –1.1 Mercury.

Mercury disappears into the twilight soon after its conjunction with Jupiter, but the outer planet continues to climb higher each morning. A telescope reveals Mercury’s gibbous disk, which shrinks from 7″ in diameter on the 1st to 5″ across at the time of its Jupiter encounter. The giant planet’s disk spans 31″ throughout October.

The Moon occults Aldebaran on the night of October 18/19. Once Luna rises around 8:30 p.m. local daylight time on the 18th, you’ll see it crossing in front of the Hyades star cluster. Observers in eastern North America can see our satellite pass in front of Theta1 (θ1) and Theta2 (θ2) Tauri. Watch as the stars reappear from behind the dark limb around 11 p.m. EDT.

The main event starts more than two hours later. Observers south of a line that runs from Southern California to the western Great Lakes can see 1st-magnitude Aldebaran dip behind the Moon’s bright limb. (Viewers along this line will see a grazing occultation, in which the star peeks in and out of view behind lunar mountains.) To find the precise times when Aldebaran disappears and reappears, visit www.lunar-occultations.com/iota/bstar/bstar.

| WHEN TO VIEW THE PLANETS | ||

| Evening Sky | Midnight | Morning Sky |

| Venus (southwest) | Uranus (south) | Mercury (east) |

| Mars (south) | Neptune (southwest) | Jupiter (east) |

| Saturn (southwest) | Uranus (west) | |

| Uranus (east) | ||

| Neptune (southeast) | ||

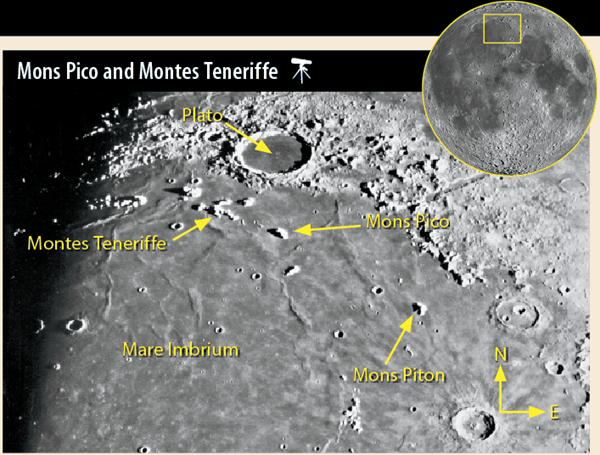

Poking through the Sea of Rains

One night after the Moon appears half-lit, at First Quarter phase on the evening of October 8, the Sun begins to rise over the lava fields of Mare Imbrium (the Sea of Rains). The returning sunlight illuminates a series of dramatic and mostly isolated mountain peaks just south of the large oval crater Plato.

One of the best examples is Mons Pico, which rises 1.5 miles above Imbrium’s floor. Throughout the evening of October 9, Pico’s shadow clearly shortens. Then, look a bit to the west and you’ll see the long triangular shadows cast by the peaks of Montes Teneriffe. Thanks to the lower Sun angle here, these shadows retreat even more quickly. You can notice changes in their lengths in as little as 15 minutes.

Astronomers used to think these mountains were volcanic, but unmanned missions in the 1960s brought a fresh perspective. Oddly enough, the breakthrough came not from close-up images of Mare Imbrium but from photos of Mare Orientale to the west. From Earth, we see only half of this feature at a steeply inclined angle.

The concentric rings of mountains surrounding Orientale were not disturbed by lava flows like Imbrium’s. Scientists inferred that only the tallest peaks of Imbrium’s original mountains — such as Mons Pico and Montes Teneriffe — survived the lava floods that filled the lowlands. Mons Piton to Pico’s southeast is another survivor.

The Hunter battles a bright Moon

October’s morning sky lights up as Earth’s atmosphere incinerates bits of comet debris. The Orionid meteor shower peaks before dawn on October 21. Unfortunately, a waning gibbous Moon shares the sky, likely cutting the observed number in half from an expected peak of 15 meteors per hour. But don’t give up. If you position yourself with the Moon at your back (preferably behind some trees or buildings), you’ll increase the chances for a good show.

Orionid meteors stem from debris left behind by Comet 1P/Halley during its regular visits to the inner solar system. Although Halley last visited 30 years ago, the debris spreads pretty evenly along the orbit. The Orionids appear to radiate from near the right elbow of Orion the Hunter.

October also features the minor Southern Taurid shower, which derives from Comet 2P/Encke. Its peak arrives on the 10th, when the Moon is absent from the prime observing hours after midnight. Observers under a dark sky can expect to see up to 5 meteors per hour.

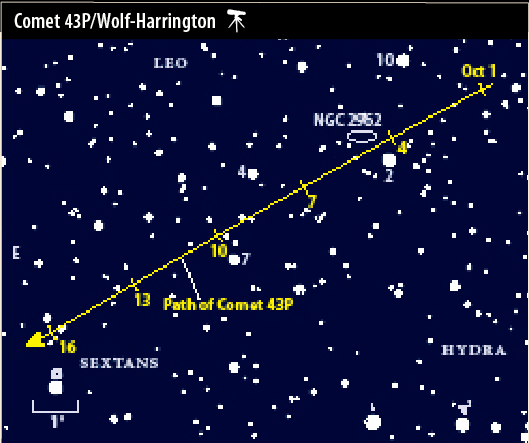

A periodic visitor on its final legs?

October’s magnificent predawn sky hosts a comet that should be a treat for observers using 8-inch or larger telescopes. With Orion and its sparkling luminaries riding high in the south, sweep east to Leo’s front paw near the Lion’s border with Hydra and Sextans to find 11th-magnitude Comet 43P/Wolf-Harrington. Head out to the country during October’s first two weeks to avoid both city lights and moonlight. The month’s last weekend will work too, as Jupiter clears the horizon and heralds the end of the night.

When viewed through a telescope, Wolf-Harrington should appear quite small and slightly out of round. Its eastern flank should be well-defined because this is where the solar wind pushes the comet’s dust away from the Sun. Compare it with the 12th-magnitude galaxy NGC 2962, which lies within a couple of degrees during October’s first week.

Wolf-Harrington’s proximity to Jupiter is not just a line-of-sight effect. The comet will swing near the gas giant in 2019, and the massive planet will fling the puny comet onto a slightly different path. Thereafter, 43P will orbit farther from the Sun and stay beyond the visual reach of 8-inch scopes.

Our current drought of decent telescopic comets should end in a few months with a deluge. Astronomers expect at least five of them to peak at 9th magnitude or brighter. The first to arrive, in December, will be 45P/Honda-Mrkos-Pajdusakova. It should reach 6th magnitude in February. And Comet 2P/Encke should brighten steadily during January and February evenings. These fine visitors will show more details if you polish your observing skills now.

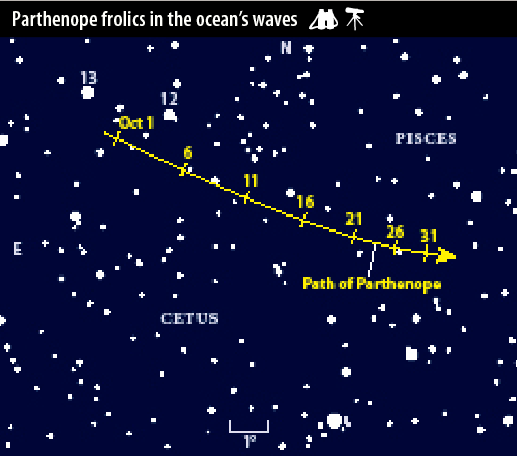

Listen to the Whale’s siren song

Astronomers used to describe asteroids as “vermin of the sky” because they interfered with more “important” observations of the universe beyond the solar system. Today, many astroimagers consider artificial Earth satellites equally pesky because they leave unwanted streaks in astrophotos. October’s sky offers a rare chance to view both a bright asteroid and some Earth-orbiting satellites at the same time.

Italian astronomer Annibale de Gasparis discovered asteroid 11 Parthenope in 1850. In Greek mythology, Parthenope was a siren of the sea who founded the city of the same name (now Naples). The asteroid lurks near the border between Pisces the Fish and Cetus the Whale, a region that climbs high in the southeast by midevening.

First locate magnitude 3.5 Iota (ι) Ceti, and then slide north to Parthenope. The 9th-magnitude asteroid will show up through tripod-mounted binoculars or a telescope.

While observing Parthenope, you also might see some objects closer to home. The asteroid lies near the band of geostationary satellites. Although these geosats orbit above Earth’s equator, our northern perspective makes them appear slightly south of the celestial equator — at a declination of about –5° for observers in the southern United States and at –7° from near the Canadian border. The Earth-satellite-Sun geometry in October gives us a direct reflection off the geosats’ solar panels, and the biggest ones can hit 4th magnitude at their peak. You can follow them by turning your telescope’s drive off — the satellites will remain stationary while the stars (and Parthenope) drift by.