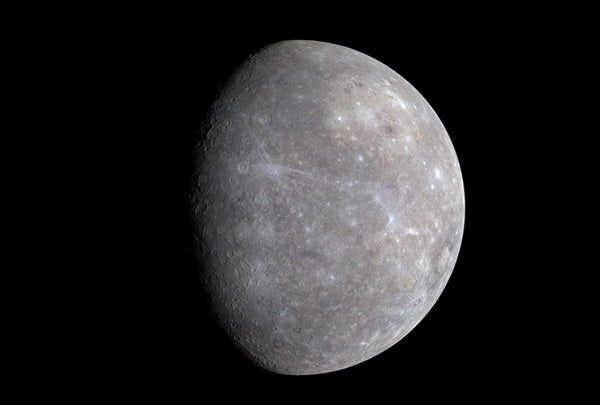

The innermost planet in our solar system is unique and odd in so many ways that it’s hard to find aspects that aren’t strange. The way it moves, the way it looks, its features, and other newly discovered oddities all conspire to create a carnival of curiosities.

For centuries, observers fighting solar glare caught fleeting glimpses of the planet’s blotchy surface markings, leading them to conclude that one of Mercury’s hemispheres always faces sunward — the way the Moon forever aims one side at Earth. This made sense. With the nearby Sun pulling on it with 10 times the gravitational force we experience here, why shouldn’t its spin have wound down, syncing its rotation to its 88-day orbital period?

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

But radar pulses in the 1960s showed that the innermost planet actually spins in 58.6 days. This means that three of its rotations — 3 Mercury days (58.6 x 3) — happen in the same interval as two of its years (88 x 2). This 3:2 resonance between its day and its year means we see the same face of Mercury every second time it orbits the Sun. So those venerable observers weren’t quite wrong. They did observe repeating patterns — but on alternate orbits. No doubt they just shrugged off the observations when the markings didn’t fit.

Mercury also has the most lopsided, out-of-round orbit of any planet in the solar system. Its Sun distance mutates from 28.5 to 43 million miles (46 to 69 million kilometers). This is huge because its solar intensity thereby varies from six to 14 times versus what we experience on Earth. Around the mercurian perihelion, its closest approach to our star, be sure to use SPF 2 billion sunblock instead of your usual 1 billion.

The innermost planet’s eccentric orbit also makes this crater-covered world speed up and slow down more than any other in our solar system, a variation that sometimes makes a sunrise on Mercury stop in its tracks and reverse itself. The Sun comes up, goes back down, and then rises a second time. Its orbital “ovalness” makes Mercury sometimes pull 18° away from the Sun from our perspective, when it reaches the “edge” of its orbit. But at other times, it can venture 27° out. This geometry lets us see the planet more easily from our Southern Hemisphere and explains why the great astronomer Copernicus supposedly never observed Mercury, confined as he was to northern Europe.

Mercury’s brightness also changes more than that of any other planet, varying by an astonishing 7.5 magnitudes. In 2015, it will go from magnitude 5.3, fainter than the “Seven Sisters” of the Pleiades, to –2.2, nearly twice the brilliance of the Dog Star Sirius, the brightest in our sky. And while Venus looks brightest when it’s near to us and appears as a crescent, Mercury shines most brilliantly when it’s farthest from us because it then displays a nearly full phase.

As if jealously resenting Venus’ greater dazzle, Mercury might actually smash our sister planet to pieces sometime in the next 5 billion years. Thanks to perturbations caused by the Sun and especially Jupiter, Mercury’s orbit wildly changes shape. It goes from circular to having an eccentricity of 0.46 — more than twice as lopsided as it is at present. Squashed like this, its orbit could actually reach innocent Venus, the planet with the most perfectly circular orbit of all.

Earth, Mars, and Saturn all tilt 20-something degrees as they spin, but Mercury alone rotates straight up and down — not even 1/10° offset from perfectly vertical. This means that at its poles, half the solar disk always sits below the horizon. Standing within the slightest polar depression or crater on Mercury, you’d never see the Sun at all. Result: permanently dark places, filled with ice. Yes, strangely enough, the nearest planet to the Sun has ice deposits extensive enough to be detectable from Earth. They offer winter sports on a world badly needing it.

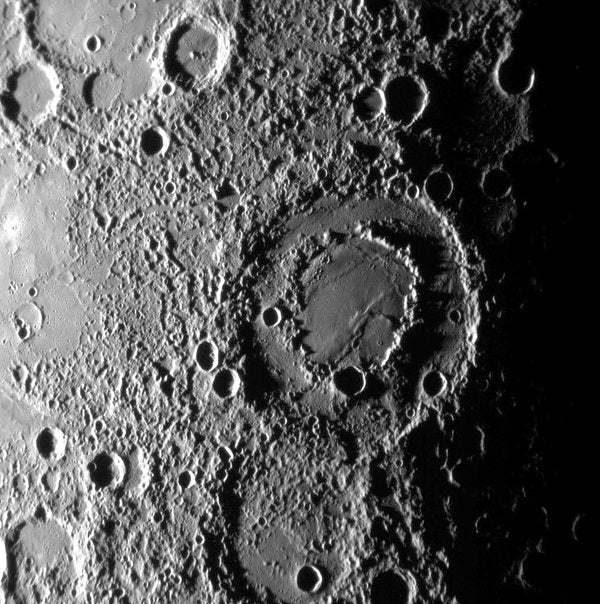

And even that isn’t the end of mercurian strangeness. One of its two largest impact features, and its most visually striking by far, is the enormous Caloris Basin. At its antipodal point — the spot on Mercury’s other side precisely opposite this basin — is the so-called Weird Terrain. This hilly region is unlike anything else on the planet. Apparently, shock waves or possibly debris from the colossal meteor impact that formed Caloris traveled around the planet’s surface and then collided at the antipodal point, wreaking havoc there.

Mercury continued to surprise scientists when the MESSENGER spacecraft entered orbit around the planet in 2011. For instance, according to Deputy Principal Investigator Larry Nittler, geochemical measurements have revealed a surface poor in iron, but rich in moderately volatile elements such as sulfur and sodium. MESSENGER observations also have shown that Mercury’s surface was shaped by volcanic activity, identified unique landforms shaped by loss of volatile materials, and confirmed that not only does the planet have ice, but that’s there is large amounts of it — all protected from the Sun’s heat within permanently shadowed impact craters near the planet’s poles.

This year, MESSENGER faces impact with the planet it was sent to investigate as the spacecraft runs out of fuel. But its results confirm that Mercury is one of a kind — an anomaly innermost world.