First envisioned in 1783, black holes epitomize mystery and danger like no other object ever known. The singularities at their cores are utterly inexpiable by science — prowlers in the inaccessible alleyways beyond our comprehension.

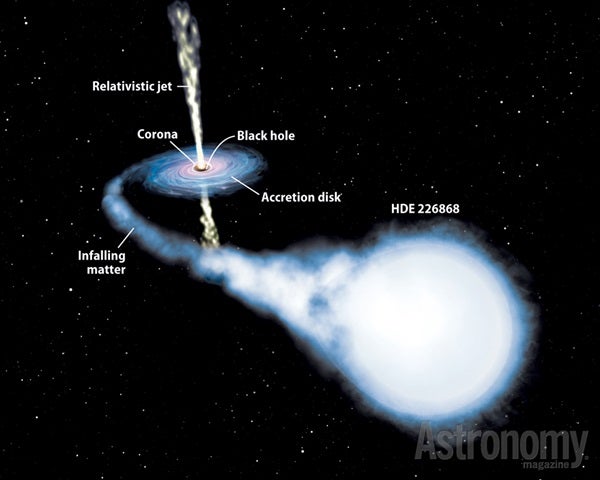

We can ease our way into this shaky realm by exploring the surest black hole in the heavens. In the lovely constellation Cygnus, the star Eta (η) Cygni dimly marks the Swan’s neck. A Moon-width to Eta’s northeast sits a blue star just bright enough to appear in binoculars. Going by the catchy name HDE 226868, it weighs somewhere between 10 and 20 Suns.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

Something fishy is going on here. First off, this bloated blue star whirls in a circle every 5.6 days, as if caught in the gravitational grasp of an immense object. Spectroscopic orbital analysis proves its companion must weigh 8.7 solar masses and lie about 20 million miles (30 million kilometers) away from it — fairly close. Yet the celestial sumo wrestler twirling HDE 226868 around like a puppet remains strangely invisible. Massive stars are always extremely bright; this star-hurler should be brilliant. Instead, our most powerful telescopes reveal no trace of anything there. Thus, we have exhibit A: a heavy, under-luminous object.

Next, this spot of sky emits an intense beam of X-rays, a powerful type of energy that’s always a sign of violence. Physics tells us that anything spiraling toward a black hole should be whipped to speeds frenzied enough to cause X-rays. Sure enough, this is the most brilliant, high-energy X-ray source in the sky, forming exhibit B. In fact, this clue is so important that this entity is universally known by its name in X-ray catalogs: Cygnus X-1.

Finally, tremendous changes in the X-ray intensity occur in a millisecond, a thousandth of a second — faster than an eye blink. Such near-instantaneous variations prove Cygnus X-1 is no larger than 1/20 the size of the Moon, exhibit C. Put all the evidence together, and you’ve got a nearly ironclad case for a black hole.

The dimension into which black holes take us is as bewildering as downtown Guatemala City. Yet many of their features are simple. They can have no magnetic field, for example, nor a reachable surface. We use these facts to eliminate other tempting candidates like neutron stars (which must always weigh less than three Suns, in any case). If infalling material headed toward a neutron star, it would release energy upon impact. But a black hole’s infalling atoms only create X-rays while in orbit; they never terminate with any sort of decisive bang.

Black holes, undeniably, have had bad press. People distrust them, suspecting they’ll gobble up the universe if given the chance. But while the phrase “black hole” suggests a poorly lit piece of emptiness, they’re not holes at all. They’re places where matter is intensely present and crushed. Any object could become a black hole if squeezed enough for gravity to grow so strong that a speed greater than light’s is needed to escape. Mount Everest would become a black hole, for instance, if all of its material were crammed into the size of an atomic nucleus.

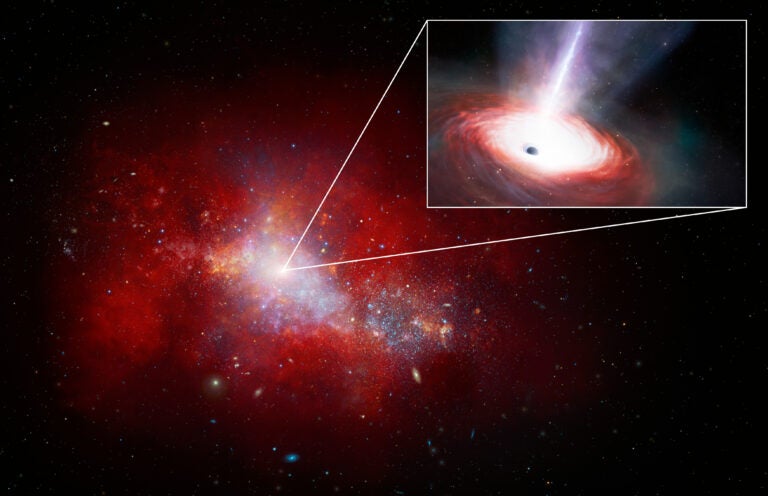

Yet black holes are scarce because matter normally does not voluntarily pack itself so firmly. The simplest mechanism involves obese stars — those more than 3½ times heavier than the Sun — going through a late-life crisis. When their nuclear furnaces no longer emit enough outward-pushing energy, such stars cannot resist the gravitational urge to collapse. The smaller they get, the smaller they want to be, until their gravitational escape velocity reaches 186,282 miles (299,792km) per second. Light itself, then, cannot leave, and the stars effectively disappear.

In a way, nothing really changes at that instant. Such a star continues shrinking, unaware that the outside world now calls it a black hole. Cygnus X-1’s singularity — the collapsed star at its center — achieved black hole density when it became 3.7 miles (6.0km) wide. Yet the star shriveled still further, to the size of a beach ball, and then an apple seed. It continued to collapse until it occupied zero volume and achieved infinite density. Well, maybe. Our laws of science cannot deal with this, and some theorists think an unknown process halts the collapse. No one knows.

If the star rotates, certain angles of approach permit hypothetical paths into other places or times. Enter exactly the right way, and you’re suddenly at the senior prom on the planet Maltese.

Surrounding the singularity is the “event horizon,” an invisible no-trespassing zone, which in Cygnus X-1’s case is 16 miles (26km) away. Step across it, and you’re doomed. When we detect this black hole’s X-rays, we hear the final frantic yelps coming to us from the visible star’s stellar wind particles caught spiraling in the accretion disk — on their way to the unknown.