The universe contains roughly 18 galaxies for every person on Earth. With such profusion, is there any reason why any of them should particularly catch our notice?

Halton Arp had the answer. Born in 1927, this Harvard and Caltech-trained astronomer always sought out the unusual while also questioning established paradigms. He even disbelieved the Big Bang theory right to his death in 2013. It’s no surprise, therefore, that his most famous work, published in 1966, goes by the title Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

Number 220 in that catalog is an odd 14th-magnitude galaxy in the constellation Serpens the Serpent. It doesn’t fit in, resembling neither a spiral nor an elliptical galaxy.

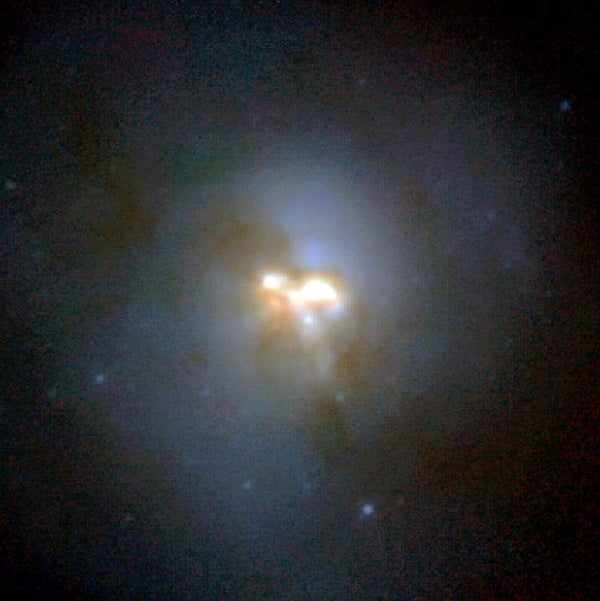

When radio telescopes and orbiting infrared observatories looked at Arp 220, its dimness vanished. In the far-infrared part of the spectrum, this is the brightest galaxy in the universe. Infrared, or heat energy, penetrates dusty gas the way visible light cannot, so what this intense infrared excess tells us is that bewilderingly hot happenings are hiding behind Arp 220’s dark molecular clouds.

All galaxies are sanctuaries of roasting heat. But to stand out so conspicuously in infrared, Arp 220 must have many millions of ultra-hot suns at the peak part of their lives shining simultaneously. Such luminous stars are always massive, with high core pressures that make them gobble up their fusion fuel in a frenzy. Thus, they soon run out of hydrogen and die young. But before they go, their starlight bakes the surrounding dust to produce that disproportionate infrared glow.

“The light that burns twice as bright burns half as long,” explained Eldon Tyrell to an impatient replicant in the sci-fi classic Blade Runner. So the crazy intensity lurking behind the swirling dark filaments in Arp 220 must be a transient phenomenon. It can’t go on. It’s happening right now only. But what would cause such a virtual explosion of new, massive, galaxy-wide star formation?

The strange shape of Arp 220 itself supplies a clue. We are looking at the result of two galaxies colliding and merging into a single entity. Such an event unfolds in slow motion so far as we short-lived humans are concerned. We merely observe a frozen portrait. If only we could have witnessed the billion-year approach of the two progenitor galaxies and their captured waltz as they whirled closer to each other. Next, we would have seen their penetration into each other’s personal space and the riotous tidal whoosh of gases merging and stars being born — only then could we understand everything that led to today’s Arp 220.

Fortunately for astronomers, with more than 125 billion other galaxies in the universe, we can view these earlier collision stages elsewhere. If you first study galaxy M82 (number 47 on our 50 Weirdest list), you will see the initial disruptive step. Here, a galaxy responds to a neighbor that came near to it but then temporarily retreated to a safe distance. Already, the symmetry of the galaxy is destroyed.

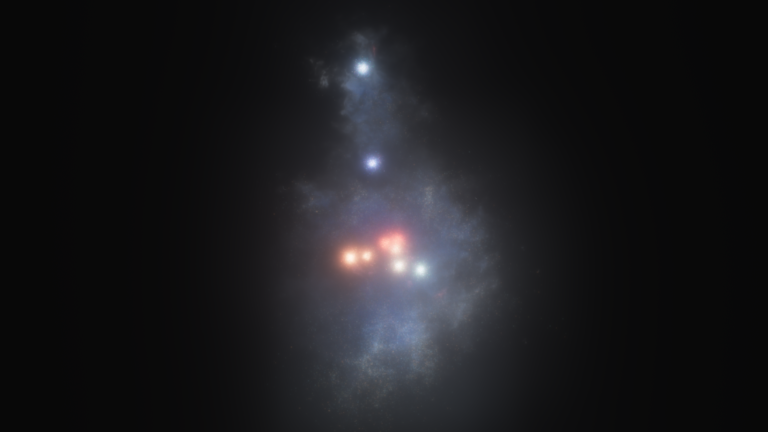

Next, the Antennae Galaxies, NGC 4038 and NGC 4039 (45 on our list), let us watch two galaxies in mid-collision.

Finally, Arp 220 reveals a further frame in the movie, a half-billion years later. The identities of the two original galaxies are now totally erased except for subtle radio features that indicate a pair of central blobs pinpointing the anemic remains of the galactic nuclei.

We can even jump ahead another half-billion years to the period after this frenzied massive star production has ended and the heavyweight stars have all died as supernovae. Now only the lower-mass yellow and orange stars still shine. The chaotic structure has settled into a ball-shaped galaxy where, like congressional study committees, nothing further will happen. To see this ultimate fate of eternal ennui, look at galaxy M87 (number 25 on our list), where the only remaining commotion comes from a supermassive black hole at its core, an entity Arp 220 is no doubt forming right now.

Arp 220 exhibits one of the most active periods in the galaxy-merger process. In its crowded, dusty center, within a region just 5,000 light-years across, the Hubble Space Telescope sees 200 colossal azure star clusters weighing as much as 10 million Suns apiece. They resemble globular clusters on steroids, like Omega Centauri (number 36 on our list). Here, in Arp 220’s center, the commotion of creation has even produced organic molecules, detected by the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico.

Spectral analysis shows that the many dazzling blue star clusters within Arp 220 were born in two flurries. One population is just 70 million years old. The other group formed a half-billion years earlier, when the galaxies first approached each other.

Such wildly active starbursts were common in the earlier universe, during an epoch of numerous galactic mergers. So galaxy Arp 220 shows us what those old Chicago gangland days were like, when the cosmos was not the well-behaved place it is today.

Astronomers now think all “ultra-luminous infrared galaxies” result from collisions and mergers. But number 220 in Halton Arp’s magnum opus is the brightest, hottest, and closest to Earth.