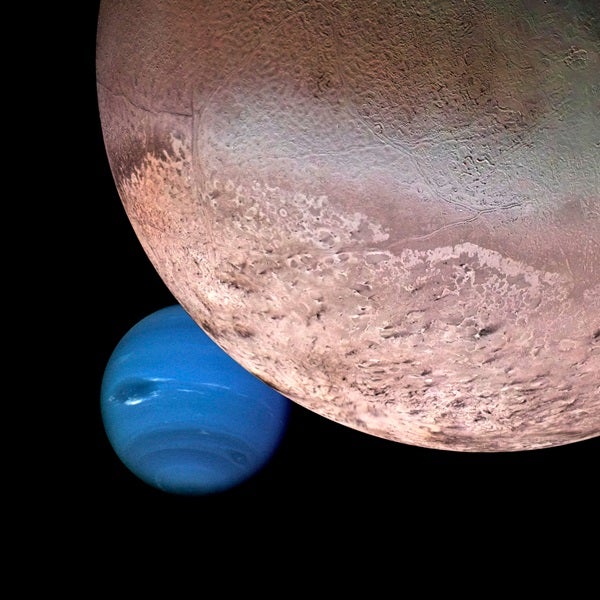

A celestial body can be weird because of how it moves. Or how it looks. Or because it embodies mysteries no one can solve. Neptune’s moon Triton possesses all three qualities.

Triton is the most distant of the solar system’s major moons — and the word “major” is important. Satellites in our solar system naturally arrange themselves into two distinct families. The major group includes those that are spherical, have a hefty mass, and follow a round orbit, suggesting an original and ancient connection with their respective planet. They are all at least 1,500 miles (2,400 kilometers) in diameter. There are only seven of these: our Moon, Jupiter’s four Galilean satellites, Saturn’s Titan, and Neptune’s Triton. Some might include an additional eight medium-sized round moons — the ones at least 600 miles (1,000km) wide: Saturn’s Tethys, Dione, Rhea, and Iapetus, and Uranus’ Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

Obviously, then, the rest of the solar system’s 158 remaining moons (not counting those orbiting asteroids or Kuiper Belt objects) are of a very different class. Typically just 10 to 20 miles (16 to 32 km) across, they’re the street dogs of the neighborhood. All are irregularly shaped, often quite far from their host planet, and fly in lopsided orbits. They should perhaps be called “moonlets.” They’re all chunks of stone or ice pulled in and captured at some point by the planet’s gravity. In other words, they did not start off where they are now.

What’s weird is if a moon of one class has some characteristic of the other. Happily for those who prize normality, only two major moons misbehave. The first is our own, the nearest satellite to the Sun, for the simple reason that it does not orbit our equator. Instead, it ignores our planet’s tilt and circles us in the same plane in which the planets orbit the Sun. The other major oddball is the farthest major moon from the Sun, Triton. Although it’s enormous and enjoys a perfectly circular orbit, it flies around Neptune backward.

This alone proves it didn’t form near Neptune during the time when the planets were born. Instead, despite its size, it was captured. Almost identical in size to former-planet Pluto, it was apparently sucked in by Neptune’s tremendous gravity.

Figuring out how this scenario could result in such a circular and well-behaved orbit requires some mathematical gymnastics. The model that works best is that Triton was once a giant double-body roaming the outer solar system. Passing Neptune, Triton lost enough energy to be captured, while its companion gained energy and was expelled. Odd indeed. This pinball game made Triton the only major moon in our solar system that orbits clockwise, as seen from above all the planets’ north poles.

Its distance from Neptune closely matches our Moon’s separation from Earth. But whereas our satellite takes nearly a month to complete an orbit, Triton finishes a circuit in just 5.88 Earth days, yanked violently by Neptune’s gravity, which is 17 times greater than ours. Like our Moon, it keeps one side permanently facing its blue parent planet.

Weirdness number two: geysers. Triton is the fourth object we know of to harbor active, ongoing eruptions. Like Saturn’s moon Enceladus, the material vented from below is not hot, but cold. This was obvious during the brief time the one-and-only spacecraft to ever visit Triton shot photographs — the amazing Voyager 2 in August 1989. The venting gas appears to be nitrogen mixed with a little dust, which then freezes onto the ground.

Voyager 2 saw a reddish surface that is young, not old, since it has very few craters. Nor was this youth caused by tectonic shifts or regions crashing together to push up mountains. Indeed, unlike the Everest-sized peaks on our Moon and Saturn’s Iapetus, nothing on Triton is higher than 3,000 feet (900 meters). Rather, its surface seems entirely created by material seeping from below and spreading out. And not hot things like lava, but cold stuff, like a water-ammonia mix that oozes from volcanoes and freezes solid. Triton is the second-coldest place any spacecraft has visited, after the Pluto system thanks to the 2015 New Horizons flyby.

The source of the heat for its volcanoes and vents remains a puzzle. Our Moon, about 28 percent larger than Triton, has only a cold core. The best guess is that its relatively high density, twice that of water, indicates it harbors a large rocky core with maybe enough radioactive material to maintain the warmth.

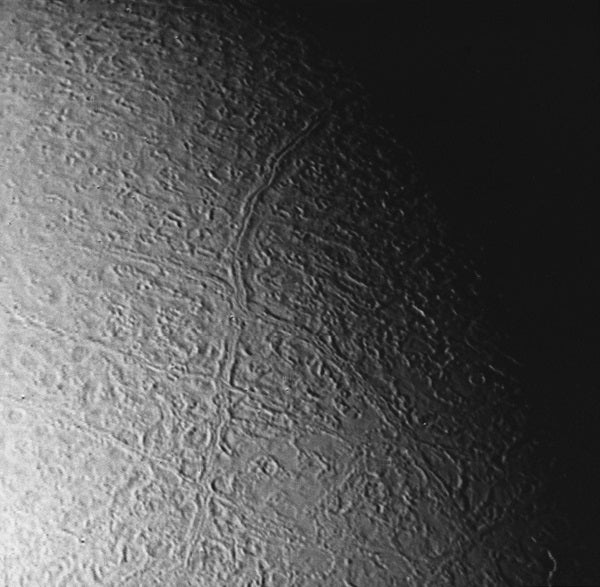

Weirdness number three: Triton looks like a cantaloupe. Bizarre depressions and fissures each 20 miles (30km) across dominate its western hemisphere. We call it “cantaloupe terrain” because it perfectly resembles the skin of that tasty melon.

Where else do we see cantaloupe terrain? Nowhere in the universe. Maybe the cause is “diapirism” — bubbles of light material rising up through denser surface stuff. But the truth is, nobody knows. Triton is unique.

Nitrogen geysers, volcanoes of watery ammonia, a cantaloupe surface, and the whole shebang orbits backward. Anyone think Triton doesn’t belong on our list?