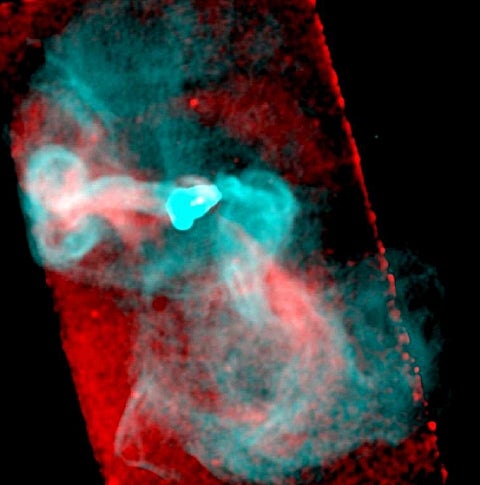

Exploding cigar

Situated about 10 million light-years away, M82 is a popular starburst galaxy possessing extremely intense clusters of young stars. A team of astronomers from the United States and United Kingdom used land and space-based observatories to grab images that show explosive gas clouds shooting into the surrounding area.

Combining images from the Hubble Space Telescope and the WIYN Telescope (a consortium consisting of the University of Wisconsin, Indiana University, Yale University, and the National Optical Astronomy Observatories), astronomers from University College London and the University of Wisconsin-Madison have traced the origin of the massive jets of hot gas into the starburst heart of M82, also known as the Cigar Galaxy. According to the team, these winds were generated by a close call with its neighboring spiral galaxy, M81. That near impact set off an eruption of star formation.

“This powers plumes of hot gas that extend for tens of thousands of light-years above and below the disk of the galaxy,” explains University College London astronomer Linda Smith. “The jets of gas from this pulsating cosmic shower are traveling at more than a million miles an hour into intergalactic space.” — Jeremy McGovern

The shortest asteroid orbit

An asteroid designated 2004 JG6, discovered earlier this month, orbits the Sun in just 6 months — the shortest orbital period of any asteroid known.

On May 10, Brian Skiff of Lowell Observatory found an unusual asteroid as part of LONEOS, one of five NASA-funded efforts to discover near-Earth objects. The Minor Planet Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts, published a preliminary orbit for the asteroid on May 13.

Only planet Mercury orbits closer to the Sun than 2004 JG6. The object passes less than 30 million miles from the Sun every six months. It may pass as close as 3.5 million miles to Earth and 2 million miles of Mercury depending on the planets’ locations. Astronomers estimate that the object is between 0.3 and 0.6 miles (500 meters to 1 kilometer) across, but despite its proximity to Earth, it poses no threat.

Asteroids with orbits entirely within that of Earth have informally been called “apoheles,” from the Hawaiian word for orbit. Dynamicists believe such objects comprise just 2 percent of the near-Earth object population. As many as fifty apoheles comparable in size to 2004 JG6 may exist, but discovery is difficult because they stay in the daylight sky almost all the time. — Francis Reddy

It’s one big universe . . .

What is the shape of space? This is the question Neil Cornish (Montana State University) and colleagues have attempted to answer using the first year of data from the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP).

The idea that space might fold back on itself in some weird way dates back to speculations Karl Schwarzschild made in 1900. Suppose, for example, that our section of space-time is just one tile in a repeating mosaic, but that light wrapping around the edges gives us the illusion of infinitude. In such a topology, light from a single, distant object could reach Earth via more than one path. The result: multiple images and a hall-of-mirrors universe.

If the universe were finite and smaller than the apparent distance to the cosmic microwave background (CMB), then multiple images should show up in the CMB. Cornish and his colleagues looked for pairs of circles, in opposite sky directions, with similar CMB temperature patterns. They found none, which means that if the universe is finite, our tile cannot be smaller than 78 billion light-years across. In other words, their study rules out any finite-universe model smaller than this characteristic size.

With improved maps of the CMB, their results can be extended to exclude universes smaller than about 91 billion light-years. At larger scales, they say, the circle-statistic technique no longer constrains the size of the cosmos. The study will appear in a forthcoming issue of Physical Review Letters. — Francis Reddy

. . . and perhaps a bit older, too.

Deep under Italy’s Gran Sasso Mountain, an experiment designed to reproduce nuclear fusion reactions inside stars has determined that those reactions happen more slowly than anticipated. This implies that stars — and indeed the entire universe — are slightly older than previously thought.

The latest results from the Laboratory for Underground Nuclear Astrophysics (LUNA) indicate that the oldest globular clusters, which contain the universe’s most ancient stellar populations, are at least 14 billion years old. This is a bit older than recent estimates placing the age of the universe at 13.7 billion years, a number based on WMAP results.

The study will be published in Physics Letters B in June, and a second paper will appear in Astronomy & Astrophysics. — Pamela Zerbinos

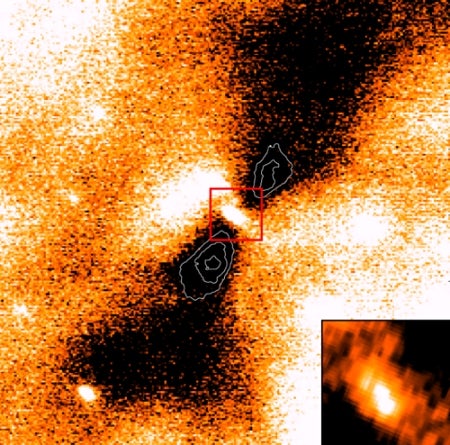

X-ray plumes in M87

NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory has revealed plumes, bubbles, and jets of gas spanning thousands of light-years in the heart of M87, a giant elliptical galaxy in the Virgo galaxy cluster. Gas falling toward the galaxy’s central black hole produces a magnetized jet that blasts high-energy particles into space at near the speed of light. The jet was first detected as a “spike” in photographs of the galaxy as far back as 1918. As the jet plows into surrounding gas, it creates a buoyant, magnetized bubble of particles. Some astronomers believe faint, ring-like features in the new Chandra image may be caused by an intense sound wave rushing ahead of these expanding bubbles. Curved plumes of X-ray emission extend more than 75,000 light-years from the galaxy’s center. Astronomers believe buoyant bubbles created by outbursts tens of millions of years ago pushed out the gas making up these features.

A growing body of evidence suggests that supermassive black holes in giant galaxies undergo episodic outbursts. Once the gas around the black hole cools, it flows inward and produces an outburst of energy that heats the gas. This again shuts down the inflow of matter to the black hole for a few million years, until the gas cools down. — Francis Reddy

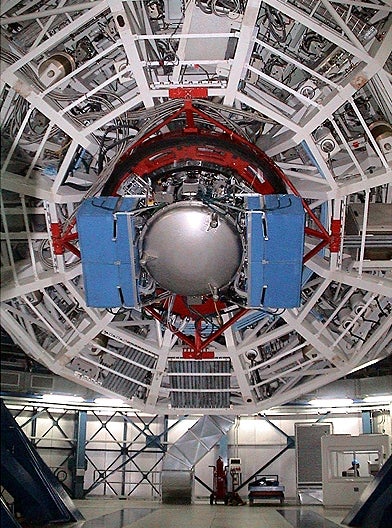

Transiting exoplanets

Following eight half-night observations in March with the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, a team of European astronomers has announced the discovery and study of two new exoplanets. Using the VLT’s FLAMES multi-fiber spectrograph, the astronomers surveyed the radial velocity of 41 stars, searching for a brief decline in brightness. This may indicate the transit of another body in front of the star. For two of the stars, OGLE-TR-113 and OGLE-TR-132, the calculated velocity changes showed the presence of planetary-mass companions in short-period orbits.

While the presence of a transit event alone does not reveal the type of transiting body, astronomers can use radial-velocity observations of the host star to determine the nature of the transiting object. The velocity-deviation sizes are directly related to the mass of the partner object, enabling astronomers to find out whether a star or planet is causing the brief dip in brightness. — Jeremy McGovern

Possible new method of finding extrasolar planets

For the first time, astronomers may have imaged a planet outside our solar system using a difficult method that enables them to find dim objects usually lost in the light of their stars. Researchers need to make follow-up observations before making a definitive claim of discovery, but if true, it would represent a significant breakthrough in the hunt for extrasolar planets. These planets, which scientists have been detecting since 1995, have mostly been photographed indirectly. But, according to John Debes of Pennsylvania State University, new observations made with the Hubble Space Telescope’s infrared NICMOS camera may reveal a different picture.

Aiming Hubble at areas around white dwarf stars, astronomers take two pictures — the second picture after rolling the telescope slightly in space. Comparing the two images allows astronomers to subtract scattered light caused by instrument imperfections and reduce the stars into more point-like sources. The remaining points of light then can be identified as orbiters or background objects.

Researchers expect to know for sure in six months whether this new method works. Debes presented his results last week at the annual symposium of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland. — Pamela Zerbinos

Astronomers at the European Southern Observatory’s Paranal Observatory in Chile reported “first light” — or, more accurately, “first heat” — for a new infrared instrument mounted on its 8.2-meter Very Large Telescope (VLT). The VLT Imager and Spectrometer in InfraRed (VISIR) can detect dust particles at temperatures of -200° to +300° C (-328° to 572° F). Many important astrophysical processes, including star formation and evolution, occur in regions obscured by dust, and infrared astronomy allows astronomers to peer into these otherwise hidden regions. Although NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope also sees in the infrared, the high cost of space-based instruments has limited its diameter to 0.85m, giving it a resolution only one-tenth that of the VLT’s.

— Pamela Zerbinos

A team of European astronomers led by Rolf Chini (Ruhr University, Bochum, Germany) has shown that high-mass stars can form in the same way as low-mass stars, that is, through accretion at the center of a circumstellar disk. Astronomers used infrared instruments to peer inside star-forming region M17. In association with an hourglass-shaped reflection nebula, they observed a silhouette resembling a flared disk seen almost edge-on. Astronomers interpret this system as a newly forming high-mass star surrounded by a huge accretion disk and accompanied by an energetic bipolar mass outflow. The disk is more than 20,000 AU across and has a mass estimated at 110 suns, making it the largest circumstellar disk ever detected. These observations corroborate recent theories that claim stars up to 40 times the mass of the Sun form through the same processes that create lower-mass stars.

— Pamela Zerbinos