Impact craters’ disappearing act

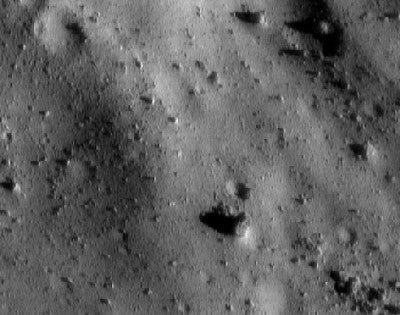

When the Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous (NEAR) mission orbited Eros between February 2000 and 2001, scientists expected to find a significant number of small craters pocking the asteroid’s surface. Instead of some 400 small craters per square kilometer, however, they found roughly 40. Why? Modeling by University of Arizona scientists indicates regolith, a loose layer of gravel that coats Eros’ body, has filled in the holes. Collisions with space debris create seismic vibrations that shake the gravel into the craters, erasing them. The team estimates this process has erased about 90 percent of Eros’ impact craters smaller than 328 feet (100 meters) in diameter.

Not only does this finding provide insight into the asteroid’s internal structure, which is critical knowledge if an asteroid sample-return mission is ever planned, but it also tells scientists about life in the asteroid belt. Earth-based telescopes have cataloged few small main-belt asteroids, so astronomers use cratering records on large asteroids to estimate the small-asteroid population. As team member James E. Richardson, Jr., notes, “We know the small asteroids — those between the size of a beach ball and a football stadium — are out there. It’s just that their ‘signature’ on asteroids such as Eros is being erased.” The team’s results were published in the November 26 issue of the journal Science.

— Laura Baird

Supermassive black hole formation curiosities

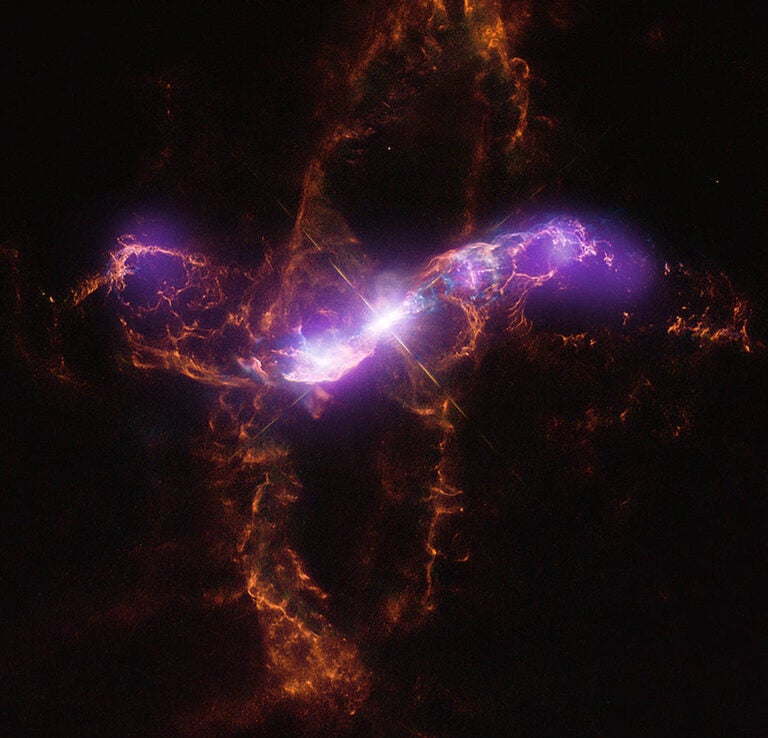

NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory recently obtained evidence that a fully-grown supermassive black hole generating energy at the rate of 20 trillion suns exists inside a quasar formed less than 1 billion years after the Big Bang. The discovery helps our understanding of the early development of supermassive black holes.

On November 19, 2003, astronomers Daniel Schwartz and Shanil Virani of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, observed the quasar, known as SDSSp J1306 (or J1306). Schwartz and Virani found J1306’s distribution of X rays with energy — or X-ray spectrum — is indistinguishable from that of nearby, older quasars. Likewise, J1306’s relative brightness at optical and X-ray wavelengths is similar to that of nearby quasars. Optical observations suggest the mass of the black hole is about 1 billion solar masses.

Although precise details of the X-ray production are not known, observations of numerous quasars — galaxies containing supermassive black holes — show many have similar X-ray spectra, especially at high X-ray energies. This discovery suggests the basic geometry and mechanism for these objects are the same.

The remarkable similarity of the X-ray spectra of the young and old supermassive black holes means supermassive black holes and their accretion disks were present less than 1 billion years after the Big Bang.

How this object formed remains a mystery. One possibility is that millions of 100-solar-mass black holes formed from the collapse of massive stars in the young galaxy. Subsequently, they built up a billion-solar-mass black hole in galaxy’s the center through mergers and accretion of gas.

To answer the question of how and when supermassive black holes were formed, astronomers plan to use the very deep Chandra exposures and other surveys to identify and study quasars at even earlier ages. — Matthew Quandt

Deep impact

A teacher at St. Matthew’s Roman Catholic School in Manchester, England, delivered some bad news at yesterday’s morning assembly. Scientists, she told hundreds of 13- and 14-year-old students, had informed the school that a meteor would strike Earth in 10 days, destroying everything in its path, so she was sending everyone home to say goodbye to loved ones. By the time she admitted she made the story up — to encourage students to “seize the day” — tears were flowing freely.

The story appears in today’s edition of The Sun, a London newspaper, and comes complete with a graphic of a flaming meteor poised to strike the school. In light of Astronomy‘s December cover story, “Killer impact,” the best quote comes from one complaining parent: “The school motto is ‘Seek ye first the kingdom of God,’ but perhaps it should be ‘Watch out for falling rocks.'” — Francis Reddy

Extraterrestrial digs

Is it time to start protecting space sites for future archaeologists? P. J. Capelotti, writing in the November/December issue of Archaeology, suggests it is. University of Hawaii anthropologist Ben Finney actually promoted this idea in 1993. Finney, who spent much of his career exploring the techniques used by Polynesians to colonize Pacific islands, suggested his future counterparts may one day similarly analyze Russian and American space sites on the Moon and Mars.

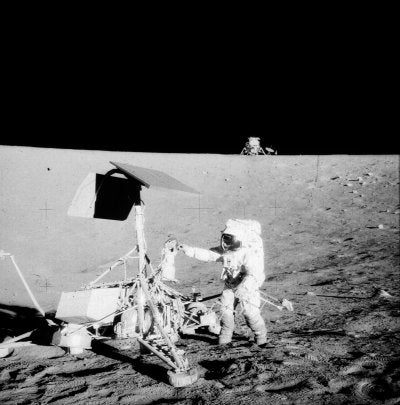

Capelotti, a senior lecturer in anthropology and American studies at Penn State University Abington College in Abington, reminds us that archaeological fieldwork has already occurred on the Moon. On November 19, 1969, astronauts Charles “Pete” Conrad and Alan Bean set down the Apollo 12 lunar module in the Moon’s Oceanus Procellarum (Ocean of Storms), just a few hundred feet from Surveyor 3, a probe that landed April 19, 1967. The astronauts cut off the probe’s television camera, remote sampling arm, and pieces of tubing. They bagged and labeled the pieces, and then returned the artifacts for multidisciplinary study on Earth.

Writes Capelotti: “As such, the mission of Apollo 12 provided the first example of aerospace archaeology, extraterrestrial archaeology and — perhaps more significant for the history of the discipline — formational archaeology, the study of environmental and cultural forces upon the life history of human artifacts in space.” — Francis Reddy

Tibet rising?

Spectacular rift valleys punctuate the Tibetan Plateau, Earth’s highest-elevation region. The valleys formed during the Indian subcontinent’s collision with Asia and, according to conventional geological wisdom, run straight north to south. To Paul Kapp, assistant professor of geosciences at the University of Arizona, Tucson, this description never seemed quite accurate, but he couldn’t put his finger on the problem.

When Kapp and doctoral candidate Jerome Guynn stripped away secondary faults from a digital elevation model of the region, they noticed the valleys clearly arc east and west from the point of India’s impact. In Tibet, he says, “We’re in a place where continents are slamming against each other. Instead of Tibet crumpling like an accordion, we see these rift valleys. The rifts are from the east-west stretching of the plateau.”

Digital elevation models developed from satellite imagery were so detailed they obscured the underlying structure. “It took me 8 years to recognize the pattern,” Kapp says. “It took me 2 days to come up with an explanation.”

Kapp and Guynn challenge leading theories, which suggest Tibet reached its zenith 8 million years ago and has been slowly deflating as it spreads out over India. Instead, they say, the head-on collision with India formed crustal rifts — geological stretch marks — curving from the line of impact, and the 3-mile-high (4.9 kilometer) Tibetan Plateau is getting even higher as the Indian subcontinent slides beneath it.

“I think there will be some serious arguing for probably the next 5 years,” Kapp says. The report appears in the November issue of the journal Geology. — Francis Reddy

Beta Centauri weighs in

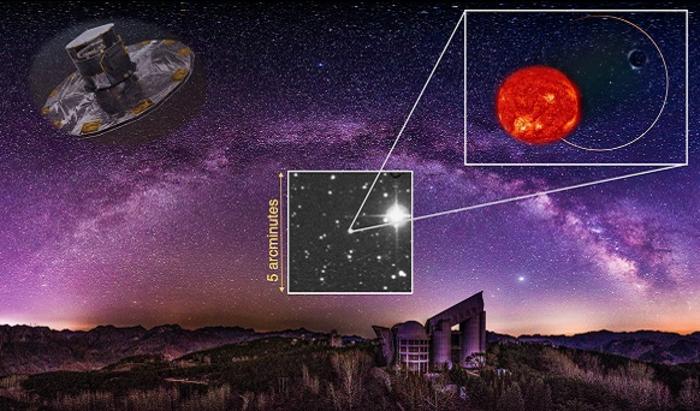

Although little known to most stargazers in the Northern Hemisphere, Beta Centauri is the 11th brightest star in the night. It’s just 4.5° west of Alpha Centauri, the Sun’s nearest neighbor. Now, astronomers have measured Beta Centauri’s mass and distance.

Knowing a star’s mass is crucial, because mass dictates how fast a star evolves and how it dies. Beta Centauri’s main star consists of two nearly identical blue giants that pulsate every few hours and orbit each other every 357 days. John Davis of the University of Sydney in Australia and his colleagues in Australia and Europe used interferometry and spectroscopy to establish that each blue giant has 9.1 solar masses.

Comparing the true and apparent sizes of the orbit yielded Beta Centauri’s distance: about 330 light-years, nearly 200 light-years less than the Hipparcos satellite determined. Hipparcos likely erred, say the scientists, because the blue giants’ orbital motion marred the parallax the spacecraft measured. A fainter star orbits the blue giants but probably didn’t affect the Hipparcos parallax.

The new distance means Beta Centauri is about as far from Earth as Alpha, Beta, and Delta Crucis, the three bright blue stars in the Southern Cross. They’re a few degrees west of Beta Centauri. — Ken Croswell

Serendipitous asteroid

Many amateur and professional astronomers invest countless hours observing, hoping to locate an asteroid. Others are fortunate enough to find an asteroid when not looking for one.

Simone Marchi, Yazan Momany, and Luigi Bedin of the University of Padova in Italy found a previously unknown asteroid while scouring August 2003 Hubble Space Telescope images of the Sagittarius dwarf irregular galaxy. The asteroid trail appears as 13 reddish arcs across the image. The camera’s shutter closed each time image data was transferred, interrupting the trail.

The new found asteroid was 169 million miles (272 million kilometers) from Earth at the time of the observation. Based on the object’s observed brightness, the team estimates its diameter at 1.5 miles (2.4 km). — Jeremy McGovern

One way to understand the K-T extinction, which eliminated 70 percent of species on Earth, is to study the animals that survived it. Reptiles like crocodiles and turtles, for example, were hardy enough to weather the “nuclear winter” thought to follow an asteroid impact 65 million years ago. Their survival provides insight into the post-impact environment.

The latest to bear witness is the tropical honeybee, Cretotrigona prisca. Amber-preserved specimens of this bee are almost indistinguishable from — and are probably the ancestors of — some modern tropical honeybees, according to Jacqueline Kozisek, a paleontology graduate student at the University of New Orleans. Looking at the survival requirements of modern species serves as a benchmark for the environment experienced by the fossil bees.

Although impact scenarios call for dust and sulfur-dioxide to have been thrown into the stratosphere, which would have cooled the planet by as much as 22° F (12° C), Kozisek finds that post-impact cooling could not have dropped temperatures more than 13° F (7° C) without wiping out the bees. The ideal temperature range for modern tropical honeybees — 88° to 93° F (31-34° C) — also happens to be the range that’s best for their food source: nectar-rich flowering plants.

“I’m not trying to say an asteroid impact didn’t happen,” says Kozisek, “I’m just trying to narrow down the effects.” She presented her work November 8 at the Geological Society of America’s annual meeting in Denver. — Francis Reddy

Oversize KBO

A Spitzer Space Telescope survey of 30 Kuiper Belt objects (KBOs) shows a very curious member. Survey scientists found 2002 AW197 to be more reflective than expected. Because size estimates for KBOs are based on how much light they reflect, the team’s results cut AW197’s size in half, to about 435 miles (700 kilometers) in diameter.

Previous estimates of the object’s size were based on the assumption that it reflected 4 percent of incident light, thought to be a reasonable estimate for KBOs and comets. Using this value, astronomers figured AW197 to be around 930 miles (1,500 km) wide – nearly two-thirds the size of Pluto. But Spitzer’s Multiband Imaging Photometer measured the object’s reflectivity, or albedo, at 18 percent. If AW197’s shinier surface is common among the KBO population, then current size estimates for these objects are way off.

“We’re finally starting to get data on the basic physical parameters of KBOs,” says University of Arizona astronomer John Stansberry, a member of the team that analyzed the Spitzer data. “That will help us determine what their compositions are, how they evolve, how massive they are, what their real size distributions and dynamics are, and how Pluto fits into the whole picture.”

Stansberry and his team will continue their study over the next year. — Jeremy McGovern

Which came first, black holes or giant galaxies?

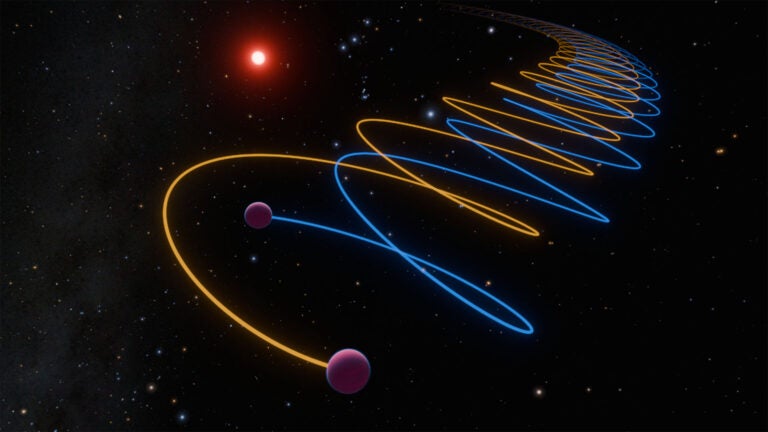

The bigger a galaxy’s central black hole is, the more stellar mass its central “bulge” component has. Astronomers have long noted this relationship, wondering whether the black hole or the stellar bulge forms first. Leading theories suggest these two structures arise at the same time, but new observations with the Very Large Array (VLA) radio telescope indicate that, for at least one giant galaxy, the black hole came first.

Chris Carilli of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory led the study, which looked at a quasar dubbed J1148+5251. Quasars are strong radio sources in the centers of distant galaxies. Discovered in 2003 by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, J1148+5251 is the most distant quasar yet found, at more than 12.8 billion light-years away.

“We found a large amount of gas in this young galaxy, and when we add the mass of this gas to that of the black hole, they add up to nearly the total mass of the entire system,” says Carilli. “The dynamics of the galaxy imply that there isn’t much mass left to make up the size of the stellar bulge predicted by current models.”

Not only could Carilli and colleagues tally the system’s molecular gas, they were able to measure gas motions, which indicate the galaxy’s total mass. Estimates of the black hole’s mass run from 1 to 5 billion suns. The researchers found about 10 billion solar masses of molecular gas in the system, with a stellar bulge of 40-50 billion suns. The trouble is, the bulge is grossly underweight — it should be trillions of suns — for theories that form the bulge and black hole at the same time.

“One example certainly doesn’t make the case, but in this object, we apparently have an example of a black hole without much of a stellar bulge,” Carilli says. “Now we need to make detailed studies of more such objects in the far-distant, early universe.”

— Francis Reddy

50,000 and counting

On September 25, NASA’s Mars Exploration Rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, reached a landmark: They’ve captured a total of 50,000 images of the martian terrain. The milestone image shows Spirit’s camera calibration target, the most-photographed subject on Mars.

Since January 2004, Spirit and Opportunity have provided images ranging from microscopic soil views to peeks of the martian horizon and the Red Planet’s moons, the Sun, and Earth. Both rovers have performed beyond expectations. After having successfully completed their initial 3-month missions and then their first mission extensions, Spirit and Opportunity began a second set of extended missions October 1. — Jeremy McGovern