At a press conference held this morning at the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Paris headquarters, members of the Huygens spacecraft science team showed that Titan is just as alien — just as weird — as scientists first guessed it might be.

“The early speculation was pretty good,” said Tobias Owen of Hawaii’s Institute of Astronomy. “We see seas of liquid methane. … It’s a flammable world — quite extraordinary.”

Sniffing Titan’s atmosphere

After a 7-year journey from Earth and a 3-week cruise from its mother ship, NASA’s Cassini orbiter, the European Space Agency’s Huygens probe plummeted through Titan’s thick atmosphere to a successful landing last week. Cassini served as the “middleman” in getting the precious information back to Earth. It pointed its antenna at Huygens throughout the descent, then turned toward Earth to relay the data.

Huygens deployed a sequence of three parachutes to slow down and sample the atmosphere in exquisite detail. During the 2.5-hour-long descent, the onboard instruments studied the atmosphere’s temperature, pressure, density, wind speed, and composition.

One surprise: No evidence of primordial argon or krypton, inert gases inherited from the solar nebula at the time Titan formed. Huygens was capable of detecting primordial argon at levels 1,000 times lower than Earth’s. Even more surprising was the discovery of argon 40, which can only form by radioactive decay inside Titan. This is the chemical fingerprint of volcanic activity — except on Titan, the lava is melted ice instead of molten rock.

Seeing the surface

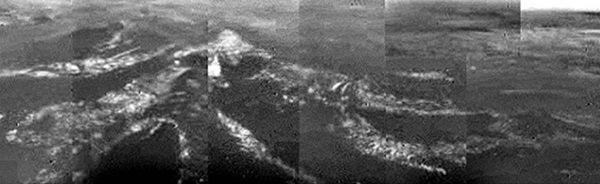

“We now have the key to understanding what shapes Titan’s landscape,” said the University of Arizona’s Martin Tomasko, principal investigator for the instrument. “Geological evidence for precipitation, erosion, mechanical abrasion, and other fluvial activity says that the physical processes shaping Titan are much the same as those shaping Earth.”

“Methane plays the same role on Titan as water does on Earth,” said Jean-Pierre Lebreton, ESA’s Huygens project scientist and mission manager.

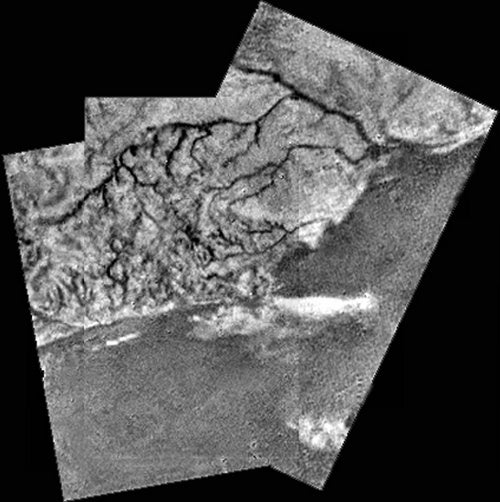

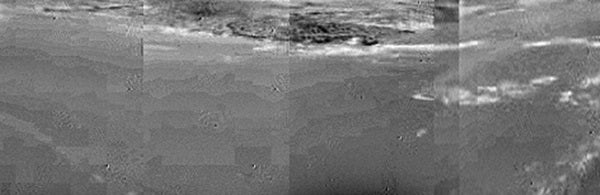

Images show complex networks of narrow drainage channels running from brighter highlands to lower, flatter, dark regions. By combining images into stereo pairs, scientists found the highlands rise as much as about 330 feet (100 meters) above the flatter regions. Channels merge into river systems that empty into the dark lowlands. Elliptical features there strongly suggest the pooling of liquid.

Dark, organic particulate matter formed in the atmosphere settles on highland ridges. Methane rainfall washes this material down the slopes and into channels that empty into temporary methane lakes.

In some places, the channels appear short and stubby. Tomasko said these features probably correspond to erosion from “springs” of liquid methane, rather than rain.

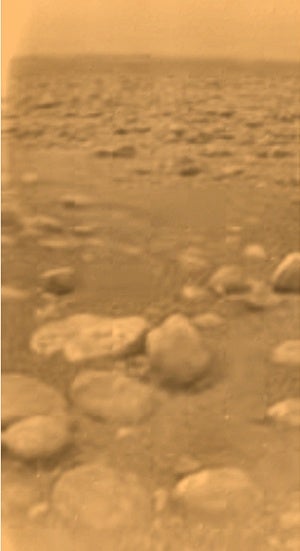

An image from the surface shows Huygens landed in an area strewn with icy pebbles, which can be seen extending to the horizon. Some of the pebbles appear to be embedded in and eroding out of the surface. The undersides of some pebbles also appear eroded — another sign of surface fluids.

Taking these images, said Tomasko, was like photographing “an asphalt parking lot at dusk.” Even the bright highlands reflect only 12 percent of the available sunlight.

Touching Titan

After descending by parachute for 2.5 hours, the probe struck Titan at a speed of 10 mph (16 km/h) and jolted to a stop with a deceleration of 15 Gs.

The temperature of the landing site: –291° F (–180° C). Despite the cold, Huygens continued transmitting data for more than one hour after landing — far longer than scientists had hoped for.

The landing thrust a penetrometer on the bottom of the saucer-shaped probe about 6 inches (15 centimeters) into the moon’s surface. According to John Zarnecki of Open University, London, the sensor initially registered a high force as it “touched the face of Titan,” but this decreased quickly, indicating the instrument had punched through a thin crust. Once through this crust, the probe pushed into soil about the consistency of wet sand.

“Already, results from Huygens are causing us to go back to the laboratory,” said Zarnecki. Scientists have been testing various materials with a duplicate version of the probe in order to determine what gives Titan’s soil its structure. The team’s best guess at the moment: finely crushed ice covered by a crust of organic material.

Huygens actually warmed Titan’s surface so much that part of it boiled away, giving the probe’s mass spectrometer a whiff of what lies beneath. “Methane is coming from the surface,” said Owen. “It’s really there in the liquid state. It might have rained yesterday.”

“Liquid methane was within a few centimeters of the surface,” noted Tomasko. “It must rain fairly frequently where we landed.”

After Huygens

Although Huygens is now a frozen part of the landscape it was sent to observe, scientists agree that the probe gave them material to study for years to come. Also, Huygens played a crucial role in further investigation of Titan by Cassini. “Huygens is providing ‘ground truth’ for Cassini’s mission, which will go on for years,” said Lebreton.

Still, the team agreed that mobility would be the next feature to bring to Titan. Possible future missions might include a balloon or a rover.

Yet Huygens stands as one of the most astonishing successes in the history of space exploration. Still buoyed by the event, ESA director of science David Southwood gushed, “Hello, America. We’re in the exploration business now, too.”