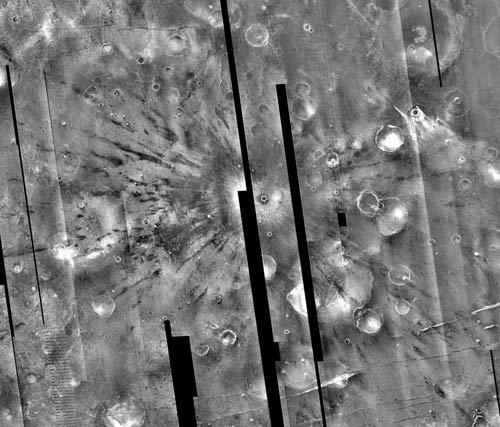

Researchers using the Mars Odyssey spacecraft have discovered a handful of small craters on Mars surrounded by far-flung patterns of rays. Ray craters are common on the Moon, but they are quite rare on Mars, where the atmosphere stops the flying jets of shattered rock that make rays after an impact.

Prior to the discovery, announced this week at the 36th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in Texas, only one ray crater had been identified on Mars. Named Zunil and spanning 6 miles (10 kilometers), the crater lies in Cerberus Planum in southern Elysium. Now a team of researchers led by Livio Tornabene of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, reports finding an additional four martian ray craters plus three probables.

“It’s fascinating we’re seeing ray craters on Mars,” Tornabene says, noting the discovery used the THEMIS infrared imager aboard Mars Odyssey.

“We didn’t find ray craters before because we were looking in visible light,” he says. “But martian ray craters don’t have the bright rays that you see on the Moon or Mercury. On Mars, rays show up in the thermal infrared.”

The ray craters cluster in two groups. A pair of them lies south of Tharsis, while the others, plus the probables, join Zunil in Elysium. The ray craters range in diameter from 1 to 4.3 miles (1.5 to 7 km), and most lie on volcanic plains dating from the most recent period in martian geological history, the Amazonian.

That suggested a link to the martian meteorites — 34 pieces (latest count) of the Red Planet that were ejected from Mars between 700,000 and 20 million years ago through impacts and which eventually fell to Earth. Their extraterrestrial origin is considered proven because the rocks contain gases matching the atmosphere of Mars as sampled by the Viking landers in the 1970s. But the meteorites’ source locations on Mars have remained stubbornly unknown.

“We’ve done incredibly exhaustive studies of these meteorites,” says Jeff Moersch, a team member also at the University of Tennessee. Adds Tornabene, “We’ve inferred an entire geological history of Mars from these meteorites, yet we don’t know where they’re from.”

“Most martian meteorite ages are young,” says Tornabene. “So most of them should come from Amazonian-age terrains — and most of our ray craters occur in Amazonian-age terrains.”

Getting rocks launched from Mars without being destroyed in the process may be a unique feature of ray craters, says Tornabene. The key is a process called spallation.

“In spallation,” Tornabene explains, “material on top of the surface close to the impact is ejected at high speed without being greatly shocked. Spallation can throw debris to great distances — or potentially off Mars.” Escape velocity from Mars is 3 miles (5 km) per second.

Impacts that hit the ground at an angle of 30° to 45° are most effective in generating spallation and ejecting lots of ray material. The craters from these moderately oblique impacts typically have asymmetric shapes and ray patterns, just as the researchers find.

Says Tornabene, “If we could send a rover to one of these sites, we could confirm the idea — or disprove it.”