The Cassini spacecraft has begun a new phase of its Saturn mission, changing its orbit around the planet to get a better look at the magnificent ring system. The probe’s new angle paid off May 1 with the discovery of a new moon, provisionally named S/2005 S1, embedded in the rings’ Keeler Gap.

Wavemaker moon

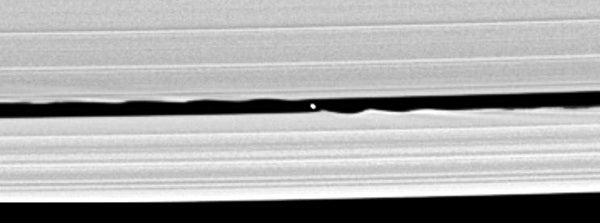

This week, mission scientists released a new image showing the tiny moon together with waves it raises at the gap’s edge. These waves precede and follow the moon as it orbits Saturn. The imaging team suspected the moon’s presence last July when they spotted wispy features in the Keeler Gap’s outer edge. Embedded moons create similar features in Saturn’s F ring and the Encke Gap, so scientists expected the Keeler Gap harbored one as well.

The Keeler Gap is about 155 miles (250 kilometers) inside the outer edge of the bright A ring. The moonlet lies about 84,820 miles (136,505 km) from Saturn’s center and completes an orbit in a little over 14 hours. It’s about 4 miles (7 km) across and reflects about half the light falling on it, which is typical of nearby ring particles.

“We anticipate that many of the gaps in Saturn’s rings have embedded moons, and we’ll be in search of them from here on,” says Carolyn Porco, imaging team leader at the Space Science Institute.

“The obvious effect of this moon on the surrounding ring material will allow us to determine its mass and test our understanding of how rings and moons affect one another,” says Carl Murray, an imaging team member from Queen Mary College at the University of London.

S/2005 S1 is the second moon known to exist within Saturn’s main rings. The other, Pan, is more than 3 times larger and orbits in the Encke Gap. The “shepherd” moons Prometheus and Pandora interact with particles in the faint, outer F ring.

Ring job

During the summer, Cassini’s main task involves studying Saturn’s rings in great detail. Much of Cassini’s flight path has been along the ring plane, which allows the spacecraft to see them only edge-on. Cassini’s orbit now tips 24º, initiating the first of three planned ring-observation periods. By the time this first ring watch ends in early September, Cassini will have completed 7 orbits, imaged the rings over a wide range of angles and illumination, and given scientists their best-ever views of the complex interplay of particles in the system.

It doesn’t end there. A second set of orbits, scheduled to begin after summer 2006, will provide views of the ring system from angles as high as 53º. Then, in the fall of 2007, controllers will increase Cassini’s inclination slowly until it reaches nearly 80º by mission’s end in summer 2008.

Phoebe crowned a KBO

Meanwhile, mission scientists continue to mine results from the spacecraft’s earlier encounters. On June 11, 2004, just 19 days before entering orbit, Cassini swept past Phoebe, Saturn’s outermost large satellite, and gave scientists their first close-up look at the battered moon. Two papers in the May 5 issue of the journal Nature detail what Cassini found.

Data from the Voyager missions, which flew past Saturn in the 1980s, led scientists to suspect Phoebe was a very primitive object. “All previous indications suggest that it may be a captured Kuiper Belt object, one of the millions of asteroid-like bodies from outside the orbit of Pluto,” said Bonnie Buratti, a Cassini scientist, shortly after the Phoebe encounter.

Cassini’s imaging spectroscope detected iron, water, carbon dioxide, organic and cyanide compounds, and more. “Detection of these compounds on Phoebe makes it one of the most compositionally diverse objects yet observed in our solar system,” reports a team led by Roger Clark of the U.S. Geological Survey. “It is likely that Phoebe’s surface contains primitive materials from the outer solar system, indicating a surface of cometary origin” much like those of Pluto and Neptune’s moon Triton, which planetary scientists believe formed in the Kuiper Belt.

Phoebe’s density, determined from knowledge of its mass and estimates of its volume from images, is about 58 percent denser than pure frozen water and similar to that of ice/rock mixtures characteristic of Pluto and Triton. “Cassini is showing us that Phoebe is quite different from Saturn’s other icy satellites, not just in its orbit but in the relative proportions of rock and ice,” says Jonathan Lunine, a Cassini scientist from the University of Arizona and co-author of one of the Nature papers. “It resembles Pluto in this regard much more than it does the other saturnian satellites.”

Not everyone agrees. University of Hawaii astronomer David Jewitt, an expert in the “irregular” moons of Jupiter and Saturn, thinks there is too little evidence for scientists to be so confident about Phoebe’s origin.

“One [of the Nature papers] states that the density of Phoebe is 1.6 grams per cubic centimeter and that this is similar to the density of Pluto, therefore Phoebe is an ex-Kuiper Belt object,” Jewitt told Astronomy. “I have rocks in my back yard that have a density of 1.6 g/cm3 but I’m pretty sure they don’t come from the Kuiper Belt. The point is that density is not a useful indicator of formation location in the way implied,” he said. “I don’t understand this paper.”

And the Clark team’s report, which details the compositional evidence, also contains a caveat: “Without information about its deep internal composition, it is not possible to conclude that Phoebe has an outer solar system origin.”

“That statement is very fair,” says Jewitt, “and is the one the press should have picked up but did not.”