Key Takeaways:

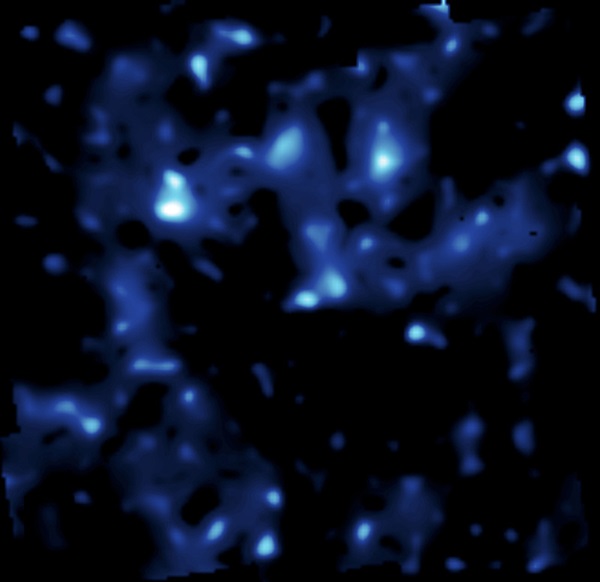

An international team of astronomers has created the first three-dimensional map of dark matter. The project, the largest ever undertaken with the Hubble Space Telescope, provides the first direct look at the large-scale distribution of dark matter in the universe.

“For the first time, we’ve been able to map out this invisible and mysterious dark matter,” says Caltech’s Richard Massey. Dark matter — a substance known only by its gravitational effect on normal matter, like stars, planets, and galaxies — accounts for most of the universe’s mass.

The milestone study required nearly 1,000 hours of Hubble time over 2 years, 400 hours of observations with the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton X-ray satellite, and galaxy color data from the Subaru, Keck, and CFHT telescopes in Hawaii and the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile.

XMM-Newton mapped the hot gas in the survey region’s galaxy clusters. This X-ray-emitting gas constitutes about 4 times the mass of a galaxy cluster’s stars. Ground-based telescopes provide the color information that allowed astronomers to determine how distant the galaxies are.

But the detailed Hubble images allowed the team to glimpse weak gravitational lensing — distortions in the shapes of background galaxies caused by intervening dark matter.

“This is the first clear view of the cosmic web,” says team member Richard Ellis of Caltech. The largest visible structures are filaments spanning 60 million light-years and containing some 2 trillion times our Sun’s mass. But because the COSMOS map includes information about the distance of objects, it’s also the first direct measure of the growth of galaxies in dark matter over time.

More distant “slices” of the map show the state of the universe at earlier times. The astronomers termed this “cosmopaleontology.”

“Dark matter collapsed first,” says Massey. “Without it, the universe as we know it today wouldn’t exist.” The map shows visible galaxies then formed within the framework established by dark matter.

“This is a tremendously exciting time,” says Ellis, noting that the weak-lensing technique is only about 6 years old. “This is now a fundamental tool of cosmologists.”

The astronomers presented their findings yesterday at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Seattle.