A new study of an unusual, elongated hydrogen cloud shows it’s on a collision course with the Milky Way. “The leading edge of this cloud is already interacting with gas from our galaxy,” said Felix “Jay” Lockman of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in Green Bank, West Virginia. He presented the findings today at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Austin, Texas.

Smith’s Cloud — named for astronomer Gail Smith, who discovered it in 1963 — showed up as an elongated source clearly separated from the Milky Way’s plane in early radio maps of neutral hydrogen. It lies south of the galactic center and spans 15° — about 30 times the apparent width of a Full Moon. “If you could see this cloud with your eyes, it would be a very impressive sight in the night sky,” Lockman said. “From tip to tail, it would cover almost as much sky as Orion.”

The cloud measures 11,000 light-years long and 2,500 light-years wide. It lies 8,000 light-years from the Milky Way’s disk and contains enough hydrogen to make a million stars like the Sun.

Until Lockman’s study, there had been little agreement about its nature. “What’s peculiar is its location and, to a lesser extent, its velocity,” he explained. “It’s out of place. If it’s part of the Milky Way, gravity should be pulling it into the plane. On the other hand, it could have been expelled — it’s pointing right at a region of star formation.” Recent studies usually class the object as one of the many so-called high-velocity clouds that surround the Milky Way. Generally just wisps of gas, these clouds fill more than a third of the sky.

Because Smith’s Cloud spans such a large patch of sky, Lockman reasoned he could determine its true space motion using the unprecedented angular resolution of NRAO’s 310-foot (100 meters) Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope (GBT). “The analogy I use is a railroad train,” he explained. If you’re standing at a crossing, train cars would show no Doppler shift because they’re moving across your line of sight. But by turning in either direction, you can see cars moving toward or away from you.

Such radial motion would produce a Doppler shift indicating which parts of the train are approaching or moving away. “So, if the thing is big enough that you can get different angles on it, you really can get the complete space motion of the object,” Lockman said. With GBT, the researchers collected data on nearly 40,000 separate locations within the cloud and were able to determine where it’s headed.

Smith’s Cloud is speeding toward the Milky Way at more than half a million miles per hour (870,000 km/h) and will impact the galaxy in less than 40 million years “When it hits, it could set off a tremendous burst of star formation,” Lockman said. Over a few million years, the impact zone will look like a celestial fireworks display, complete with many supernova “blockbusters.” The team believes the cloud impact will occur about 90 ° ahead of the Sun and slightly farther away from the galaxy’s center.

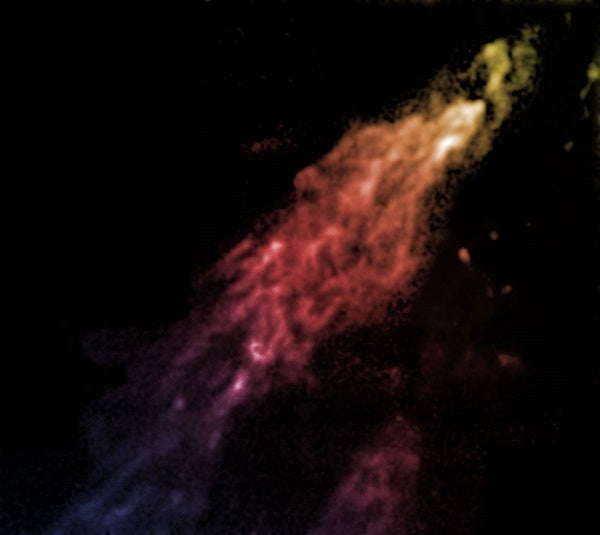

What looked like an elongated blob on early surveys becomes a structured cometary nebula under GBT’s high-resolution gaze. “It’s such a beautiful object,” Lockman said. The shape is telling: It indicates Smith’s Cloud already is hitting gas in our galaxy’s outskirts.

So, where did the cloud come from? “This has such a low total velocity that it’s absolutely bound to the galaxy. There’s no question of it being some intergalactic object,” Lockman explained. “One of the most attractive theories of high-velocity clouds is that they’re the remnants of galaxy formation.” Smith’s Cloud, he suggests, is a straggler from the Milky Way’s early days that only now is reaching the construction site.