New images from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft reveal a giant cyclone at Saturn’s north pole and show that earthlike storm patterns powered a similarly monstrous cyclone churning at Saturn’s south pole.

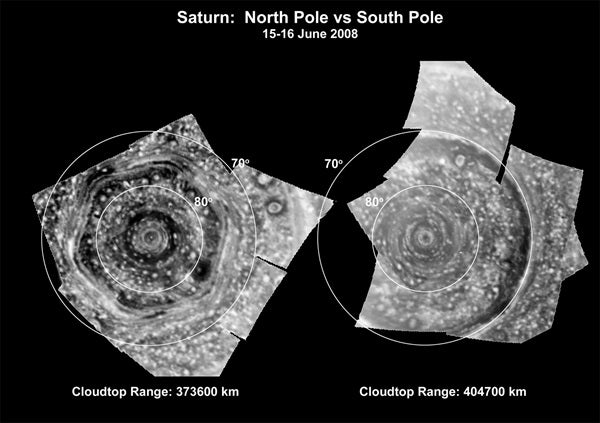

The new-found cyclone at Saturn’s north pole is only visible in the near-infrared wavelengths because the north pole is in winter, thus in darkness to visible-light cameras. At these wavelengths, about 7 times greater than light seen by the human eye, the clouds deep inside Saturn’s atmosphere are seen in silhouette against the background glow of Saturn’s internal heat.

Saturn’s entire north pole is now mapped in detail in infrared, with features as small as 75 miles (120 kilometers) visible in the images. Time-lapse movies of the clouds circling the north pole show the region’s whirlpool-like cyclone is rotating at 325 mph (530 km/h), more than twice as fast as the highest winds measured in cyclonic features on Earth. An odd, honeycomb-shaped hexagon surrounds the cyclone. This feature does not seem to move while the clouds within it whip around at high speeds, also greater than 300 mph (500 km/h). Oddly, neither the fast-moving clouds inside the hexagon nor this new cyclone seems to disrupt the six-sided hexagon.

Unlike earthbound hurricanes, powered by the ocean’s heat and water, Saturn’s cyclones have no body of water at their bases, yet the eye-walls of Saturn’s and Earth’s storms look strikingly similar. The Ringed World’s hurricanes are locked to the planet’s poles, whereas terrestrial hurricanes drift across the ocean.

“These are truly massive cyclones, hundreds of times stronger than the most giant hurricanes on Earth,” said Kevin Baines, Cassini scientist on the visual and infrared mapping spectrometer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “Dozens of puffy, convectively formed cumulus clouds swirl around both poles, betraying the presence of giant thunderstorms lurking beneath. Thunderstorms are the likely engine for these giant weather systems,” Baines said.

Just as condensing water in clouds on Earth powers hurricane vortices, the heat released from the condensing water in saturnian thunderstorms deep down in the atmosphere may be the primary power source energizing the vortex.

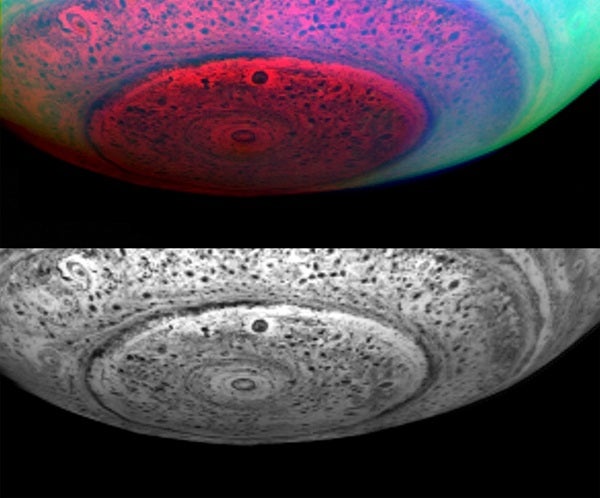

The new infrared images of the south pole, under the daylight conditions of southern summer, show that hundreds of dark cloud spots mark the entire. The clouds, similar to those at the north pole, are probably a manifestation of convective, thunderstorm-like processes extending some 62 miles (100 km) below the clouds. They are likely composed of ammonium hydrosulfide with possibly a mixture of materials dredged up from the depths. By contrast, planetary scientists suspect that ammonia — which condenses at high, visible altitudes — makes up most of Saturn’s hazes and clouds.

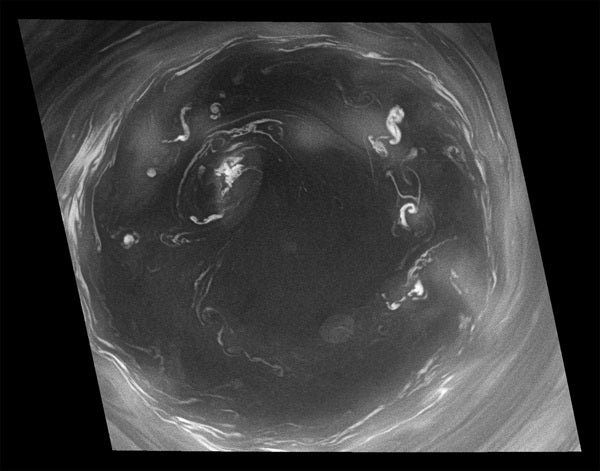

An outer ring of high clouds surrounds the “eye” of the vortex. The new images also hint at an inner ring of clouds about half the diameter of the main ring, and so the actual clear “eye” region is smaller than it appears in earlier low-resolution images.

“It’s like seeing into the eye of a hurricane,” said Andrew Ingersoll, a member of Cassini’s imaging team at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “It’s surprising. Convection is an important part of the planet’s energy budget because the warm upwelling air carries heat from the interior. In a terrestrial hurricane, the convection occurs in the eye-wall; the eye is a region of down-welling. Here convection seems to occur in the eye as well.”

Further observations are planned to see how the features at both poles evolve as the seasons change from southern summer to fall in August 2009.