An international team of radio astronomers has discovered the secret explosion of a massive star, a new supernova, in the nearby galaxy M82. Despite being the closest supernova discovered in the last 5 years, the explosion is exclusively detectable at radio wavelengths because the dense gas and dust surrounding the exploding star leave it invisible in other wavebands. Without the obscuration, this explosion would have been visible even with amateur telescopes.

M82 is an irregular galaxy in a nearby galaxy group located 12 million light-years from Earth. Despite being smaller than the Milky Way, it harbors a vigorous central starburst in the inner few hundred light-years. In this stellar factory, more stars are presently born than in the entire Milky Way. M82 is often called an “exploding galaxy” because it looks as if being torn apart in optical and infrared images as the result of numerous supernova explosions from massive stars. Many remnants from previous supernovae are seen on radio images of M82 and a new supernova explosion was long overdue. For a quarter of a century, astronomers have tried to catch this cosmic catastrophe in the act and have started to wonder why the galaxy has been so silent in recent years.

The discovery was first made in April 2009 when Andreas Brunthaler from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn, Germany, examined data just taken (April 8, 2009) with the Very Large Array (VLA) of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, an interferometer of 27 identical 25-meter telescopes in New Mexico. “I then looked back into older data we had from March and May last year,” said Brunthaler, and there it was as well, outshining the entire galaxy!” Observations taken before 2008 showed neither pronounced radio nor X-ray emission at the position of this supernova.

On the other hand, observations of M82 taken last year with optical telescopes to search for new supernovae showed no signs of this explosion. Furthermore, the supernova is hidden on ultraviolet and X-ray images. The supernova exploded close to the center of the galaxy in a very dense interstellar environment. This could also reveal the mystery about the long silence of M82 — many of these events may actually be something like “underground explosions,” where the bright flash of light is covered under huge clouds of gas and dust and only radio waves can penetrate this dense material. “This cosmic catastrophe shows that by using our radio telescopes we have a front-row seat to observe the otherwise hidden universe,” said Heino Falcke from Radboud University Nijmegen, The Netherlands. If not obscured, the explosion could have been visible even in a medium-sized amateur telescope.

Radio emission can be detected only from core collapse supernovae, where the core of a massive star collapses and produces a black hole or a neutron star. It is produced when the shock wave of the explosion propagates into dense material surrounding the star, usually material that was shed from the massive progenitor star before it exploded.

By combining data from the 10 telescopes of the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA), the VLA, the Green Bank Telescope in the USA, and the Effelsberg 100-meter telescope in Germany, using the technique of Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI), the team was able to produce images that show a ring-like structure expanding at more than 25 million miles (40 million kilometers) per hour or 4 percent of the speed of light, typical for supernovae. “By extrapolating this expansion back in time, we can estimate the explosion date,” said Brunthaler. Our current data indicate that the star exploded in late January or early February 2008.”

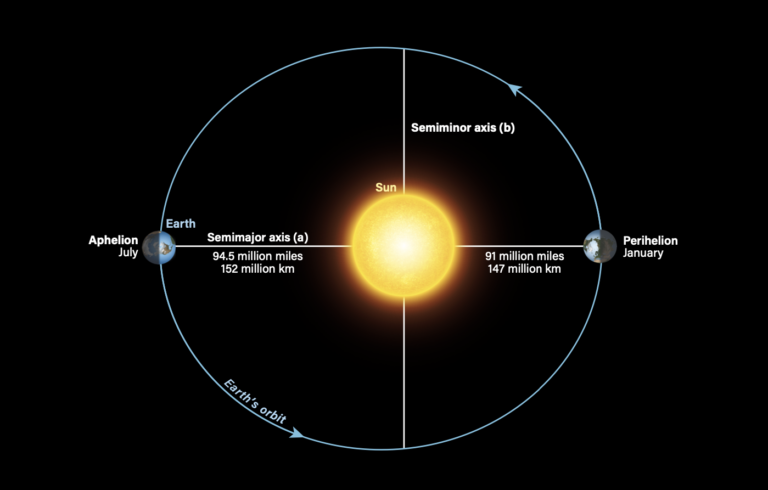

Only 3 months after the explosion, the ring was already 650 times larger than Earth’s orbit around the Sun. It takes the sharp view of the VLBI observations to resolve this structure which is as large as a 1 Euro coin seen from a distance of 8,000 miles (13,000 kilometers).

The asymmetric appearance of the supernova on the VLBI images indicates also that either the explosion was highly asymmetric or the surrounding material unevenly distributed. “Using the super sharp vision of the VLBI,” said Karl Menen, director at the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, “we can follow the supernova expanding into the dense interstellar medium of M82 over the coming years and gain more insight on it and the explosion itself.”