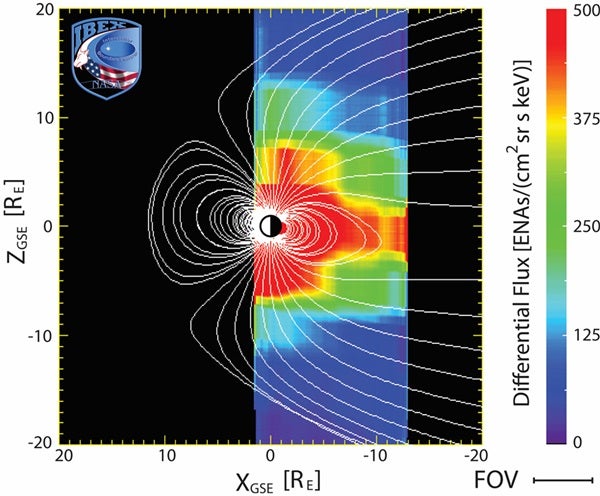

The data provide the first image of the plasma sheet, a component of the magnetosphere made up of magnetic field lines that attach to Earth at both ends, bottling up denser plasma — ionized gas — within the magnetotail, the trailing portion of the magnetosphere stretching backward away from the Sun by the force of the solar wind. The image shows the plasma sheet and magnetotail in profile.

“The image alone is remarkable and would have made a great paper in and of itself because it’s the first time we’ve imaged these important regions of the magnetosphere,” said David McComas from the Space Science and Engineering Division at Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas.

However, a closer look at the various images produced by multiple IBEX orbits revealed what appeared to be a piece of the plasma sheet being bitten off and ejected down the tail. This magnetic disconnection phenomenon — a dynamic event where the magnetic fields “reconnect” across the plasma sheet, producing what is known as a plasmoid — is one explanation for what could be occurring in the series of images, which has never been directly seen before.

“Imagine the magnetosphere as one of those balloons that people make animals out of. If you take your hands and squeeze the balloon, the pressure forces the air into another segment of the balloon,” said McComas. “Similarly, the solar wind at times increases the pressure around the magnetosphere, resulting in a portion of the plasma sheet being pinched away from the rest of the plasma sheet and forced down the magnetotail.”

Because researchers believe this phenomenon generally occurs deeper in the magnetotail, the IBEX team is considering other explanations for the event, as well. Other possibilities include acceleration of ions from compression of the plasma sheet or an injection of new plasma caused by a reconnection event farther back in the tail, with particles streaming back toward Earth.

“To actually be able to observe and image the plasma sheet and magnetotail for the first time, and especially to be able to see their dynamic variations, is extremely exciting,” McComas said.

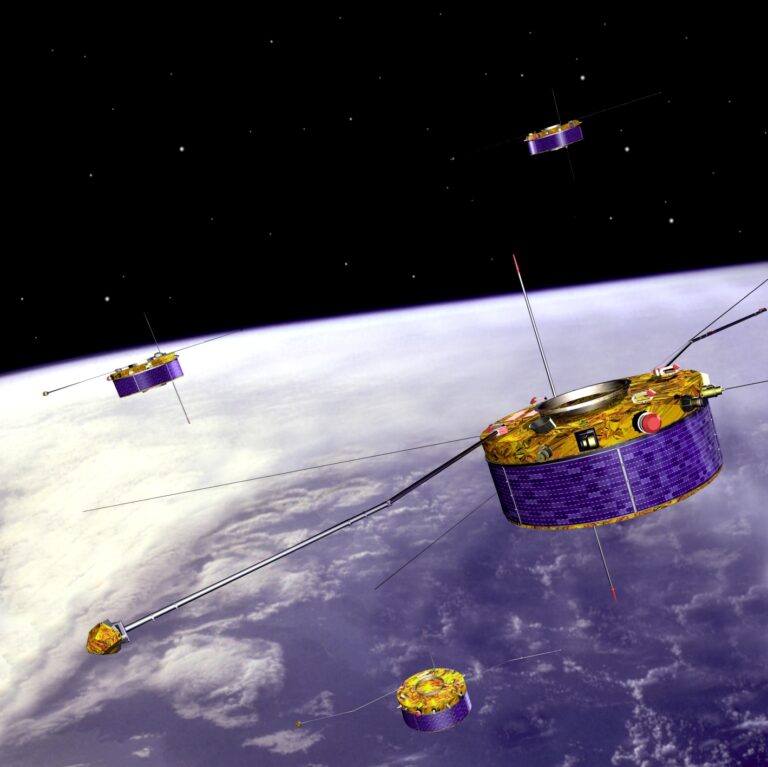

While not specifically designed to observe the magnetosphere, IBEX’s vantage point in space provides twice-yearly (spring and fall) seasons for viewing from outside the magnetosphere. Other satellites from within have taken previous images of the magnetosphere. Future IBEX images of the magnetosphere are expected to provide additional data to compare with local measurements inside the magnetosphere and build on current theories.

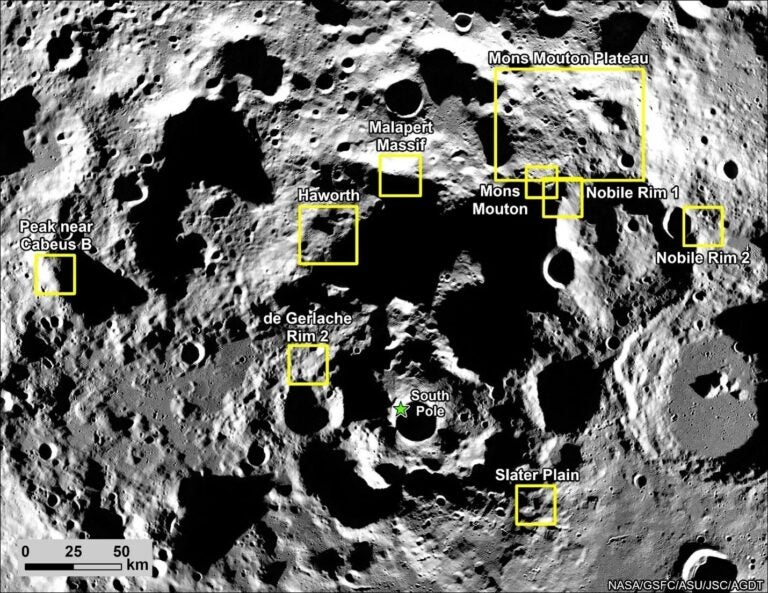

Since its October 2008 launch, the IBEX science mission has flourished into multiple research studies. In addition to studying the interstellar interaction at the edge of the solar system and doing magnetospheric science, the spacecraft has also directly collected hydrogen and oxygen from the interstellar medium for the first time and made the first observations of fast hydrogen atoms coming from the Moon, following decades of speculation and searching for their existence.

The data provide the first image of the plasma sheet, a component of the magnetosphere made up of magnetic field lines that attach to Earth at both ends, bottling up denser plasma — ionized gas — within the magnetotail, the trailing portion of the magnetosphere stretching backward away from the Sun by the force of the solar wind. The image shows the plasma sheet and magnetotail in profile.

“The image alone is remarkable and would have made a great paper in and of itself because it’s the first time we’ve imaged these important regions of the magnetosphere,” said David McComas from the Space Science and Engineering Division at Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas.

However, a closer look at the various images produced by multiple IBEX orbits revealed what appeared to be a piece of the plasma sheet being bitten off and ejected down the tail. This magnetic disconnection phenomenon — a dynamic event where the magnetic fields “reconnect” across the plasma sheet, producing what is known as a plasmoid — is one explanation for what could be occurring in the series of images, which has never been directly seen before.

“Imagine the magnetosphere as one of those balloons that people make animals out of. If you take your hands and squeeze the balloon, the pressure forces the air into another segment of the balloon,” said McComas. “Similarly, the solar wind at times increases the pressure around the magnetosphere, resulting in a portion of the plasma sheet being pinched away from the rest of the plasma sheet and forced down the magnetotail.”

Because researchers believe this phenomenon generally occurs deeper in the magnetotail, the IBEX team is considering other explanations for the event, as well. Other possibilities include acceleration of ions from compression of the plasma sheet or an injection of new plasma caused by a reconnection event farther back in the tail, with particles streaming back toward Earth.

“To actually be able to observe and image the plasma sheet and magnetotail for the first time, and especially to be able to see their dynamic variations, is extremely exciting,” McComas said.

While not specifically designed to observe the magnetosphere, IBEX’s vantage point in space provides twice-yearly (spring and fall) seasons for viewing from outside the magnetosphere. Other satellites from within have taken previous images of the magnetosphere. Future IBEX images of the magnetosphere are expected to provide additional data to compare with local measurements inside the magnetosphere and build on current theories.

Since its October 2008 launch, the IBEX science mission has flourished into multiple research studies. In addition to studying the interstellar interaction at the edge of the solar system and doing magnetospheric science, the spacecraft has also directly collected hydrogen and oxygen from the interstellar medium for the first time and made the first observations of fast hydrogen atoms coming from the Moon, following decades of speculation and searching for their existence.