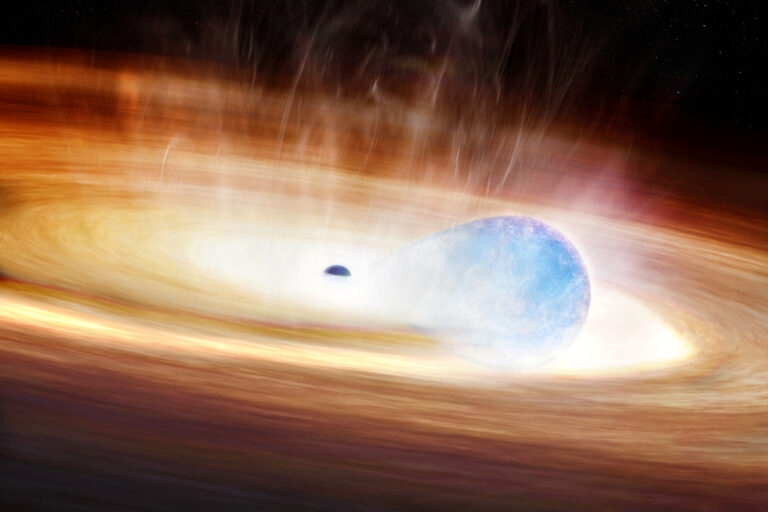

Venus is blanketed in sulfuric acid clouds that block our view of the surface. The clouds form at altitudes of 30–45 miles (50–70 kilometers) when sulfur dioxide from volcanoes combines with water vapor to make sulfuric acid droplets. Any remaining sulfur dioxide should be destroyed rapidly by the intense solar radiation above 45 miles (70 km).

So the detection of a sulfur dioxide layer at 55–70 miles (90–110 km) by ESA’s Venus Express orbiter in 2008 posed a complete mystery. Where did that sulfur dioxide come from?

Now, computer simulations by Xi Zhang from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena and colleagues from America, France, and Taiwan show that some sulfuric acid droplets may evaporate at high altitudes, freeing gaseous sulfuric acid that is then broken apart by sunlight, releasing sulfur dioxide gas.

“We had not expected the high-altitude sulfur layer, but now we can explain our measurements,” said Hakan Svedhem from ESA. “However, the new findings also mean that the atmospheric sulfur cycle is more complicated than we thought.”

As well as adding to our knowledge of Venus, this new understanding may be warning us that proposed ways of mitigating climate change on Earth may not be as effective as originally thought.

Nobel prize winner Paul Crutzen has recently advocated injecting artificially large quantities of sulfur dioxide into Earth’s atmosphere at around 12 miles (20 km) to counteract global warming resulting from increased greenhouse gases.

The proposal stems from observations of powerful volcanic eruptions, in particular the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines that shot sulfur dioxide up into Earth’s atmosphere. Reaching 12 miles (20 km) in altitude, the gas formed small droplets of concentrated sulfuric acid, like those found in Venus’ clouds, which then spread around Earth. The droplets created a haze layer that reflected some of the Sun’s rays back into space, cooling the whole planet by about 1° Fahrenheit (0.5° Celsius).

However, the new work on the evaporation of sulfuric acid on Venus suggests that such attempts at cooling our planet may not be as successful as first thought. We do not know how quickly the initially protective haze will be converted back into gaseous sulfuric acid — this is transparent and so allows all the Sun’s rays through.

“We must study in great detail the potential consequences of such an artificial sulfur layer in the atmosphere of Earth,” said Jean-Loup Bertaux from the University of Versailles-Saint-Quentin, France. “Venus has an enormous layer of such droplets, so anything that we learn about those clouds is likely to be relevant to any geo-engineering of our own planet.”

In effect, nature is doing the experiment for us, and Venus Express allows us to learn the lessons before experimenting with our own world.

Venus is blanketed in sulfuric acid clouds that block our view of the surface. The clouds form at altitudes of 30–45 miles (50–70 kilometers) when sulfur dioxide from volcanoes combines with water vapor to make sulfuric acid droplets. Any remaining sulfur dioxide should be destroyed rapidly by the intense solar radiation above 45 miles (70 km).

So the detection of a sulfur dioxide layer at 55–70 miles (90–110 km) by ESA’s Venus Express orbiter in 2008 posed a complete mystery. Where did that sulfur dioxide come from?

Now, computer simulations by Xi Zhang from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena and colleagues from America, France, and Taiwan show that some sulfuric acid droplets may evaporate at high altitudes, freeing gaseous sulfuric acid that is then broken apart by sunlight, releasing sulfur dioxide gas.

“We had not expected the high-altitude sulfur layer, but now we can explain our measurements,” said Hakan Svedhem from ESA. “However, the new findings also mean that the atmospheric sulfur cycle is more complicated than we thought.”

As well as adding to our knowledge of Venus, this new understanding may be warning us that proposed ways of mitigating climate change on Earth may not be as effective as originally thought.

Nobel prize winner Paul Crutzen has recently advocated injecting artificially large quantities of sulfur dioxide into Earth’s atmosphere at around 12 miles (20 km) to counteract global warming resulting from increased greenhouse gases.

The proposal stems from observations of powerful volcanic eruptions, in particular the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines that shot sulfur dioxide up into Earth’s atmosphere. Reaching 12 miles (20 km) in altitude, the gas formed small droplets of concentrated sulfuric acid, like those found in Venus’ clouds, which then spread around Earth. The droplets created a haze layer that reflected some of the Sun’s rays back into space, cooling the whole planet by about 1° Fahrenheit (0.5° Celsius).

However, the new work on the evaporation of sulfuric acid on Venus suggests that such attempts at cooling our planet may not be as successful as first thought. We do not know how quickly the initially protective haze will be converted back into gaseous sulfuric acid — this is transparent and so allows all the Sun’s rays through.

“We must study in great detail the potential consequences of such an artificial sulfur layer in the atmosphere of Earth,” said Jean-Loup Bertaux from the University of Versailles-Saint-Quentin, France. “Venus has an enormous layer of such droplets, so anything that we learn about those clouds is likely to be relevant to any geo-engineering of our own planet.”

In effect, nature is doing the experiment for us, and Venus Express allows us to learn the lessons before experimenting with our own world.