On January 31, University of Hawaii at Manoa astronomers used the UH 2.2-meter telescope on Mauna Kea to take the first new images in more than 3 years of the potentially dangerous near-Earth asteroid Apophis as it emerged from behind the Sun.

The object became famous in late 2004, when it appeared to have a 1 in 37 chance of colliding with Earth in 2029, but additional data eventually ruled out that possibility.

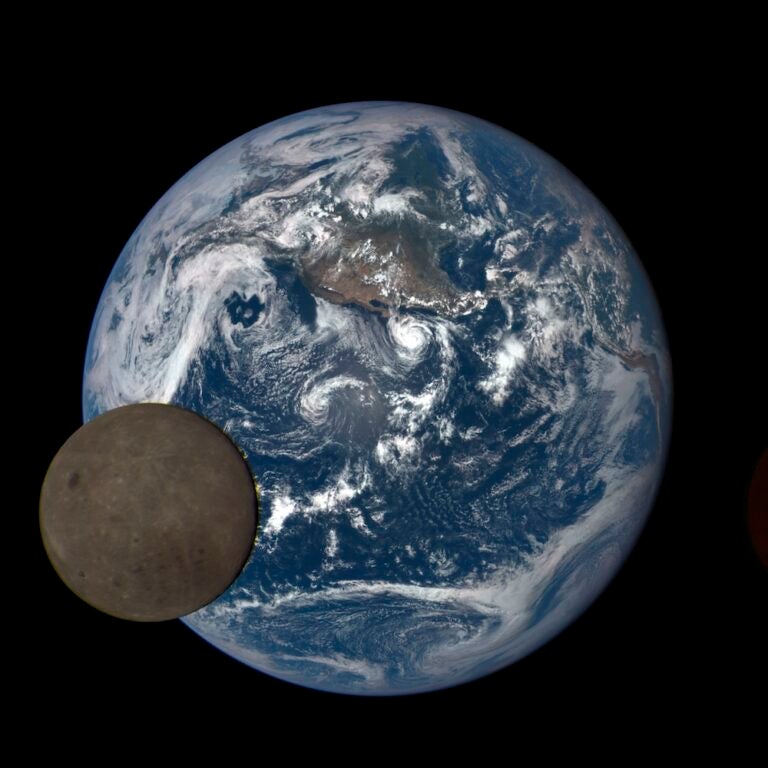

However, on April 13, 2029, the asteroid, which has a 900-foot (270m) diameter, will come closer to Earth than the geosynchronous communications satellites that orbit Earth at an altitude of about 22,000 miles (36,000 kilometers). Apophis will then be briefly visible to the naked eye as a fast-moving starlike object.

This close encounter with Earth will significantly change Apophis’s orbit, which could lead to a collision with Earth later this century. For that reason, astronomers have been eager to obtain new data to further refine the details of the 2029 encounter.

Astronomer David Tholen, one of the co-discoverers of Apophis, and graduate students Marco Micheli and Garrett Elliott obtained the new images when the asteroid was less than 44° from the Sun and about a million times fainter than the faintest star that the average human eye can see without optical aid.

“The superb observing conditions that are possible on Mauna Kea made the observations relatively easy,” said Tholen.

Astronomers measure the position of an asteroid by comparing the known positions of stars that appear in the same image as the asteroid. As a result, any tiny error in the catalog of star positions, due for example to the very slow motions of the stars around the center of our Milky Way Galaxy, can affect the measurement of the position of the asteroid.

“We will need to repeat the observation on several different nights using different stars to average out this source of imprecision before we will be able to significantly improve the orbit of Apophis and therefore the details of the 2029 close approach and future impact possibilities,” noted Tholen.

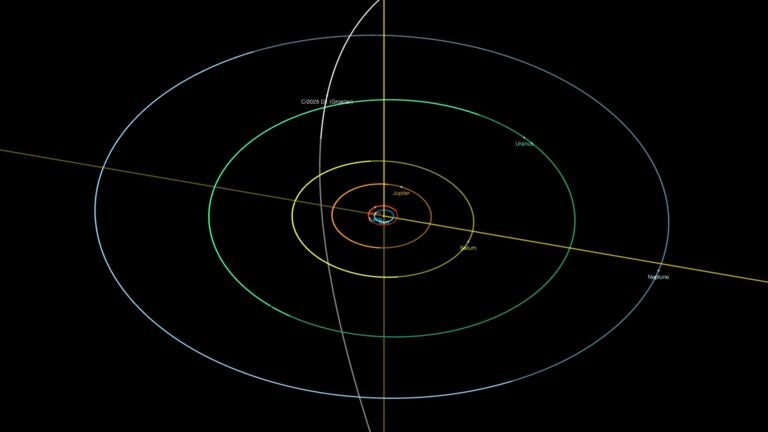

Apophis’s elliptical orbit around the Sun will take it back into the Sun’s glare this summer, inhibiting the acquisition of additional positions. However, in 2012, Apophis will again become observable for approximately nine months. In 2013, the asteroid will pass close enough to Earth for ultraprecise radar signals to be bounced off its surface.

On January 31, University of Hawaii at Manoa astronomers used the UH 2.2-meter telescope on Mauna Kea to take the first new images in more than 3 years of the potentially dangerous near-Earth asteroid Apophis as it emerged from behind the Sun.

The object became famous in late 2004, when it appeared to have a 1 in 37 chance of colliding with Earth in 2029, but additional data eventually ruled out that possibility.

However, on April 13, 2029, the asteroid, which has a 900-foot (270m) diameter, will come closer to Earth than the geosynchronous communications satellites that orbit Earth at an altitude of about 22,000 miles (36,000 kilometers). Apophis will then be briefly visible to the naked eye as a fast-moving starlike object.

This close encounter with Earth will significantly change Apophis’s orbit, which could lead to a collision with Earth later this century. For that reason, astronomers have been eager to obtain new data to further refine the details of the 2029 encounter.

Astronomer David Tholen, one of the co-discoverers of Apophis, and graduate students Marco Micheli and Garrett Elliott obtained the new images when the asteroid was less than 44° from the Sun and about a million times fainter than the faintest star that the average human eye can see without optical aid.

“The superb observing conditions that are possible on Mauna Kea made the observations relatively easy,” said Tholen.

Astronomers measure the position of an asteroid by comparing the known positions of stars that appear in the same image as the asteroid. As a result, any tiny error in the catalog of star positions, due for example to the very slow motions of the stars around the center of our Milky Way Galaxy, can affect the measurement of the position of the asteroid.

“We will need to repeat the observation on several different nights using different stars to average out this source of imprecision before we will be able to significantly improve the orbit of Apophis and therefore the details of the 2029 close approach and future impact possibilities,” noted Tholen.

Apophis’s elliptical orbit around the Sun will take it back into the Sun’s glare this summer, inhibiting the acquisition of additional positions. However, in 2012, Apophis will again become observable for approximately nine months. In 2013, the asteroid will pass close enough to Earth for ultraprecise radar signals to be bounced off its surface.