On March 17, the MESSENGER probe entered orbit around Mercury, beginning a yearlong science mission. This is the first spacecraft to orbit our innermost planet, and one of its goals is to gather data about regions never-before-seen by spacecraft.

Prior to orbiting Mercury, the probe flew by the planet three times — January and October 2008 and September 2009 — to gather data and tweak its trajectory.

MESSENGER’s orbit around the innermost planet is highly elliptical, bringing it just 129 miles (207 kilometers) above the surface at the nearest point and about 9,300 miles (15,000 km) at farthest distance. It completes two orbits per day.

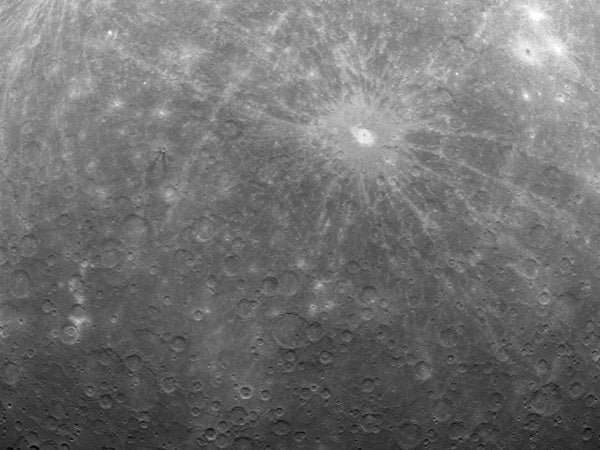

Scientists estimate the spacecraft will acquire some 80,000 images over its yearlong mission. They released the first image from MESSENGER’s new orbit March 29 and another nine March 30. Scientists expect that over the first 3 days of data (March 29 through the 31st), they will acquire 1,500 images from MESSENGER.

The spacecraft has other instruments, too, in addition to its imaging system. The other eight experiments will compile data over the next year. Scientists have already started acquiring topographic profiles of Mercury, which tell them about geological features at large scales down to individual craters. They’ve also started to map Mercury’s magnetic field. Scientists don’t understand why this planet has a magnetic field; it should have died out long ago, like that of Mars.

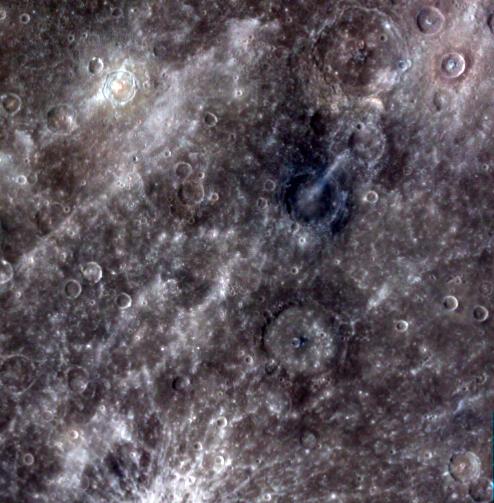

During a press teleconference, MESSENGER scientists expressed that they’re surprised how many secondary craters there are on Mercury’s surface, and how large these objects are. One of the first images they released shows a rich field of these secondary craters that come from ejecta of larger craters. This image is of a region in the extreme northern latitudes that has never been imaged by spacecraft before.

Visit NASA’s MESSENGER page to see more images.

On March 17, the MESSENGER probe entered orbit around Mercury, beginning a yearlong science mission. This is the first spacecraft to orbit our innermost planet, and one of its goals is to gather data about regions never-before-seen by spacecraft.

Prior to orbiting Mercury, the probe flew by the planet three times — January and October 2008 and September 2009 — to gather data and tweak its trajectory.

MESSENGER’s orbit around the innermost planet is highly elliptical, bringing it just 129 miles (207 kilometers) above the surface at the nearest point and about 9,300 miles (15,000 km) at farthest distance. It completes two orbits per day.

Scientists estimate the spacecraft will acquire some 80,000 images over its yearlong mission. They released the first image from MESSENGER’s new orbit March 29 and another nine March 30. Scientists expect that over the first 3 days of data (March 29 through the 31st), they will acquire 1,500 images from MESSENGER.

The spacecraft has other instruments, too, in addition to its imaging system. The other eight experiments will compile data over the next year. Scientists have already started acquiring topographic profiles of Mercury, which tell them about geological features at large scales down to individual craters. They’ve also started to map Mercury’s magnetic field. Scientists don’t understand why this planet has a magnetic field; it should have died out long ago, like that of Mars.

During a press teleconference, MESSENGER scientists expressed that they’re surprised how many secondary craters there are on Mercury’s surface, and how large these objects are. One of the first images they released shows a rich field of these secondary craters that come from ejecta of larger craters. This image is of a region in the extreme northern latitudes that has never been imaged by spacecraft before.

Visit NASA’s MESSENGER page to see more images.