One of the year’s best meteor showers makes its appearance in early May. The Eta Aquarid shower peaks the morning of May 6, although the number of “shooting stars” should be nearly as high a morning or two before and after. Observers under a dark sky can expect to see between 20 and 30 meteors per hour — an average of one every 2 or 3 minutes — at the Eta Aquarids’ peak.

And conditions should be close to perfect this year. According to Astronomy magazine Senior Editor Michael Bakich, “The waxing crescent Moon sets well before midnight, leaving the prime observing hours close to dawn Moon-free.” For the best views, find an observing site far removed from city lights.

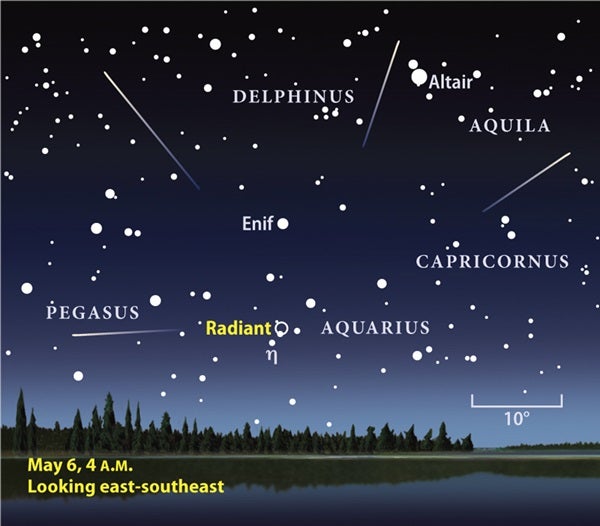

The meteors appear to radiate from a spot in the constellation Aquarius. For those who live near 40° north latitude, this radiant rises in the east around 2:30 a.m. local daylight time and climbs nearly 20° high by 4 a.m. Morning twilight begins to interfere soon thereafter, so the best views should come around 4 a.m. For observers closer to the equator or in the Southern Hemisphere, the radiant climbs much higher before dawn, so the shower could produce 50 meteors per hour.

These meteors began life as tiny specks of dust ejected by Halley’s Comet during its innumerable trips around the Sun. Over the eons, these particles spread out along the comet’s orbit. Every May, Earth runs through this stream of dust. The particles hit Earth’s atmosphere at 148,000 mph (238,000 km/h), vaporizing from friction with the air and leaving behind the streaks of light we call meteors. All the dust particles burn up high in the atmosphere, some 50 miles (80 km) above the surface. None of the particles in any meteor shower is big enough to survive its trip through our atmosphere and reach the ground.

Fast facts:

- At 148,000 mph (238,000 km/h), Eta Aquarid meteors are the second-fastest of any annual shower. Only the Leonids of November hit our atmosphere faster, at 159,000 mph (256,000 km/h).

- The Eta Aquarid meteor shower is one of two that derives from Comet Halley’s debris. The other is the Orionid shower, which peaks in October.

- Video: How to observe meteor showers, with Michael E. Bakich, senior editor

- Video: Easy-to-find objects in the 2011 spring sky, with Michael E. Bakich, senior editor

- StarDome: Locate constellation Aquarius the Water-bearer in your night sky before this meteor shower with our interactive star chart.

- Sign up for our free weekly e-mail newsletter.