“This was the first demonstration in practice of one of SOFIA’s major design capabilities,” said Bob Meyer, SOFIA’s program manager. “Pluto’s shadow traveled at 53,000 mph (85,300 km/h) across a mostly empty stretch of the Pacific Ocean. SOFIA flew more than 1,800 miles (2,900 kilometers) out over the Pacific Ocean from its base in Southern California to position itself in the center of the shadow’s path, and was the only observatory capable of doing so.”

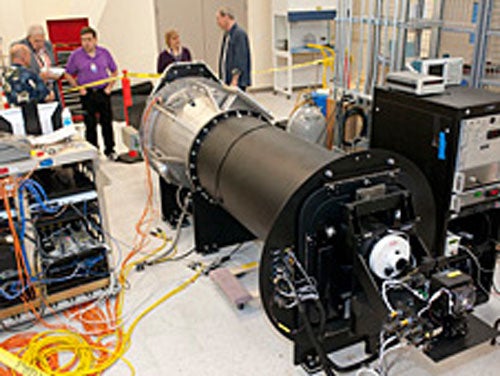

SOFIA is a highly modified Boeing 747SP aircraft that carries a telescope with a 100-inch (2.5 meters) reflecting mirror that conducts astronomy research not possible with ground-based telescopes. By operating in the stratosphere at altitudes up to 45,000 feet (13,700 meters), SOFIA can make observations above the water vapor in Earth’s lower atmosphere.

“Occultations give us the ability to measure pressure, density, and temperature profiles of Pluto’s atmosphere without leaving the Earth,” said Ted Dunham from Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona. “Because we were able to maneuver SOFIA so close to the center of the occultation, we observed an extended, small, but distinct brightening near the middle of the occultation. This change will allow us to probe Pluto’s atmosphere at lower altitudes than is usually possible with stellar occultations.”

Dunham is the principal investigator for the High-Speed Imaging Photometer for Occultation (HIPO), essentially an extremely fast and accurate electronic light meter. He was a member of the group that originally discovered Pluto’s atmosphere by observing a stellar occultation from SOFIA’s predecessor, the Kuiper Airborne Observatory, in 1988. Pluto was discovered at Lowell Observatory in 1930.

A group of SOFIA German scientists and engineers were also aboard to monitor the performance of the German-built telescope and Fast Diagnostic Camera (FDC). That camera has been used on previous flights to measure the stability of SOFIA and its optical systems. On this flight, the FDC provided supplemental observations of the Pluto occultation.

There were some tense moments for SOFIA’s international science team in the minutes leading up to Thursday’s occultation. The precise position of Pluto in relation to Earth could not be sufficiently refined until a few hours before the event. That evening, a Lowell astronomer used facilities at the U.S. Naval Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, to take multiple photographs of Pluto and the star. That data was passed to collaborators at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, who refined their prediction of the exact position and timing of Pluto’s shadow track.

About 2 hours before the occultation, the MIT group contacted SOFIA in-flight with the news that the center of the shadow would cross 125 miles (200 km) north of the position on which the airborne observatory’s flight plan had been based. After recalculating and filing a revised flight plan, SOFIA’s flight crew and science team had to wait an anxious 20 minutes before receiving permission from air traffic control to alter the flight path accordingly.

“We have already shown that SOFIA is a first-rank international facility for infrared astronomy research. This successful occultation observation adds substantially to SOFIA’s ability to serve the world’s scientific community,” said Pamela Marcum, SOFIA project scientist.

“This was the first demonstration in practice of one of SOFIA’s major design capabilities,” said Bob Meyer, SOFIA’s program manager. “Pluto’s shadow traveled at 53,000 mph (85,300 km/h) across a mostly empty stretch of the Pacific Ocean. SOFIA flew more than 1,800 miles (2,900 kilometers) out over the Pacific Ocean from its base in Southern California to position itself in the center of the shadow’s path, and was the only observatory capable of doing so.”

SOFIA is a highly modified Boeing 747SP aircraft that carries a telescope with a 100-inch (2.5 meters) reflecting mirror that conducts astronomy research not possible with ground-based telescopes. By operating in the stratosphere at altitudes up to 45,000 feet (13,700 meters), SOFIA can make observations above the water vapor in Earth’s lower atmosphere.

“Occultations give us the ability to measure pressure, density, and temperature profiles of Pluto’s atmosphere without leaving the Earth,” said Ted Dunham from Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona. “Because we were able to maneuver SOFIA so close to the center of the occultation, we observed an extended, small, but distinct brightening near the middle of the occultation. This change will allow us to probe Pluto’s atmosphere at lower altitudes than is usually possible with stellar occultations.”

Dunham is the principal investigator for the High-Speed Imaging Photometer for Occultation (HIPO), essentially an extremely fast and accurate electronic light meter. He was a member of the group that originally discovered Pluto’s atmosphere by observing a stellar occultation from SOFIA’s predecessor, the Kuiper Airborne Observatory, in 1988. Pluto was discovered at Lowell Observatory in 1930.

A group of SOFIA German scientists and engineers were also aboard to monitor the performance of the German-built telescope and Fast Diagnostic Camera (FDC). That camera has been used on previous flights to measure the stability of SOFIA and its optical systems. On this flight, the FDC provided supplemental observations of the Pluto occultation.

There were some tense moments for SOFIA’s international science team in the minutes leading up to Thursday’s occultation. The precise position of Pluto in relation to Earth could not be sufficiently refined until a few hours before the event. That evening, a Lowell astronomer used facilities at the U.S. Naval Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, to take multiple photographs of Pluto and the star. That data was passed to collaborators at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, who refined their prediction of the exact position and timing of Pluto’s shadow track.

About 2 hours before the occultation, the MIT group contacted SOFIA in-flight with the news that the center of the shadow would cross 125 miles (200 km) north of the position on which the airborne observatory’s flight plan had been based. After recalculating and filing a revised flight plan, SOFIA’s flight crew and science team had to wait an anxious 20 minutes before receiving permission from air traffic control to alter the flight path accordingly.

“We have already shown that SOFIA is a first-rank international facility for infrared astronomy research. This successful occultation observation adds substantially to SOFIA’s ability to serve the world’s scientific community,” said Pamela Marcum, SOFIA project scientist.