The birth of galaxies occurred more than 10 billion years ago in the ancient universe. Assembled under their own gravity, early galaxies formed into big clusters or small groups. During the process of assemblage, their properties changed in relation to their surrounding environments, just as human traits change in the contexts of their lives. For example, galaxies grouped in high-density environments such as clusters tend to be elliptical or lenticular while solitary ones tend to be spiral galaxies. How galaxies form and evolve is one of the biggest mysteries in recent extragalactic astronomy.

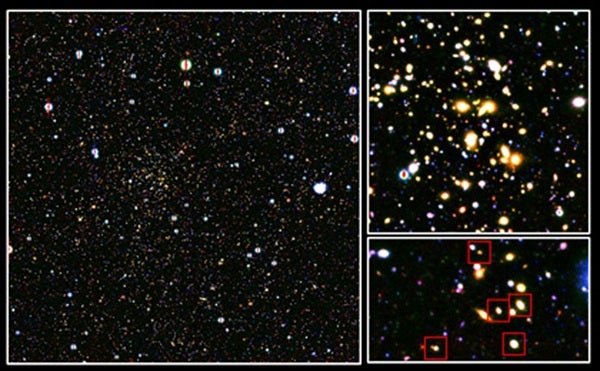

When and how did patterns of galactic formation become established and evolve? To address this question, many astronomers are investigating distant clusters of galaxies where assemblage of galaxies occurred in the early universe. A research team led by Yusei Koyama from the University of Tokyo/National Astronomical Observatory of Japan used the Subaru Prime Focus Camera (Suprime-Cam) to carry out a panoramic observation targeting a relatively well-known rich cluster,CL0939+4713, located 4 billion light-years from Earth. The team used a special filter that can detect the Hydrogen-alpha (H-alpha) line emitted by ionized hydrogen 4 billion years ago. Koyama’s team members carefully compared the images taken with and without the special filter and then identified more than 400 galaxies showing an excess of helium (He) in the special filter images. Such narrow-band “excess” galaxies are likely to be star-forming galaxies. Surprisingly, Koyama’s team found that an unexpectedly large number of star-forming galaxies had red colors. Even more interesting was the location of these red-burning galaxies — they reside primarily in the group-scale environments located far away from the main body of the cluster.

These findings raise some intriguing questions. What is the physical origin of these red-burning galaxies? Why are they concentrated in groups and not in clusters? No one, including the research team members, knows the answer yet. At a minimum, the strong H-alpha emissions clearly show that the red-burning galaxies are actively forming new stars. Therefore, their red colors are likely to be produced by dust rather than by old stellar populations. The researchers expect that the strong gravity of the main cluster will cause the groups where the red-burning galaxies are most numerous to merge with it. The most significant result of this research is that the properties of galaxies are indeed changing in relatively sparse environments before they are finally absorbed into a rich cluster.

The research team noticed that the number of old galaxies, without active star-formation, appeared to be increasing in the group environments, exactly where the red-burning galaxies are most numerous. This suggests that the red-burning galaxies are related to the increase in old galaxies, and that they are likely to be in a transitional phase from a younger to an older generation. The finding that such transitional galaxies are located most frequently within group environments shows that galaxy groups are the key environments for understanding how environment shapes the evolution of galaxies.

The research team emphasized the important contribution of the unique wide-field capability of the Subaru Telescope for accomplishing this research because its panoramic imaging revealed the location of the transitional galaxies. The same research team now plans to conduct a new observation to identify the physical origin of the red-burning galaxies discovered in this study. This should be an important and exciting step toward a more complete understanding of the environments shaping the galaxies in the present-day universe.

The birth of galaxies occurred more than 10 billion years ago in the ancient universe. Assembled under their own gravity, early galaxies formed into big clusters or small groups. During the process of assemblage, their properties changed in relation to their surrounding environments, just as human traits change in the contexts of their lives. For example, galaxies grouped in high-density environments such as clusters tend to be elliptical or lenticular while solitary ones tend to be spiral galaxies. How galaxies form and evolve is one of the biggest mysteries in recent extragalactic astronomy.

When and how did patterns of galactic formation become established and evolve? To address this question, many astronomers are investigating distant clusters of galaxies where assemblage of galaxies occurred in the early universe. A research team led by Yusei Koyama from the University of Tokyo/National Astronomical Observatory of Japan used the Subaru Prime Focus Camera (Suprime-Cam) to carry out a panoramic observation targeting a relatively well-known rich cluster,CL0939+4713, located 4 billion light-years from Earth. The team used a special filter that can detect the Hydrogen-alpha (H-alpha) line emitted by ionized hydrogen 4 billion years ago. Koyama’s team members carefully compared the images taken with and without the special filter and then identified more than 400 galaxies showing an excess of helium (He) in the special filter images. Such narrow-band “excess” galaxies are likely to be star-forming galaxies. Surprisingly, Koyama’s team found that an unexpectedly large number of star-forming galaxies had red colors. Even more interesting was the location of these red-burning galaxies — they reside primarily in the group-scale environments located far away from the main body of the cluster.

These findings raise some intriguing questions. What is the physical origin of these red-burning galaxies? Why are they concentrated in groups and not in clusters? No one, including the research team members, knows the answer yet. At a minimum, the strong H-alpha emissions clearly show that the red-burning galaxies are actively forming new stars. Therefore, their red colors are likely to be produced by dust rather than by old stellar populations. The researchers expect that the strong gravity of the main cluster will cause the groups where the red-burning galaxies are most numerous to merge with it. The most significant result of this research is that the properties of galaxies are indeed changing in relatively sparse environments before they are finally absorbed into a rich cluster.

The research team noticed that the number of old galaxies, without active star-formation, appeared to be increasing in the group environments, exactly where the red-burning galaxies are most numerous. This suggests that the red-burning galaxies are related to the increase in old galaxies, and that they are likely to be in a transitional phase from a younger to an older generation. The finding that such transitional galaxies are located most frequently within group environments shows that galaxy groups are the key environments for understanding how environment shapes the evolution of galaxies.

The research team emphasized the important contribution of the unique wide-field capability of the Subaru Telescope for accomplishing this research because its panoramic imaging revealed the location of the transitional galaxies. The same research team now plans to conduct a new observation to identify the physical origin of the red-burning galaxies discovered in this study. This should be an important and exciting step toward a more complete understanding of the environments shaping the galaxies in the present-day universe.