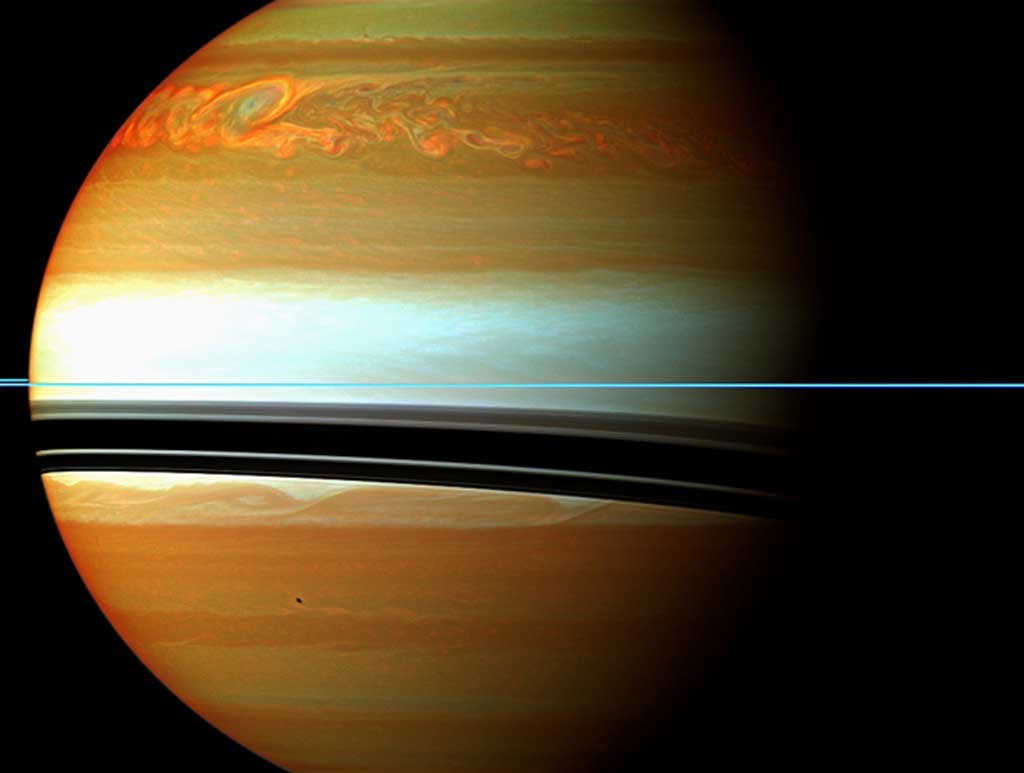

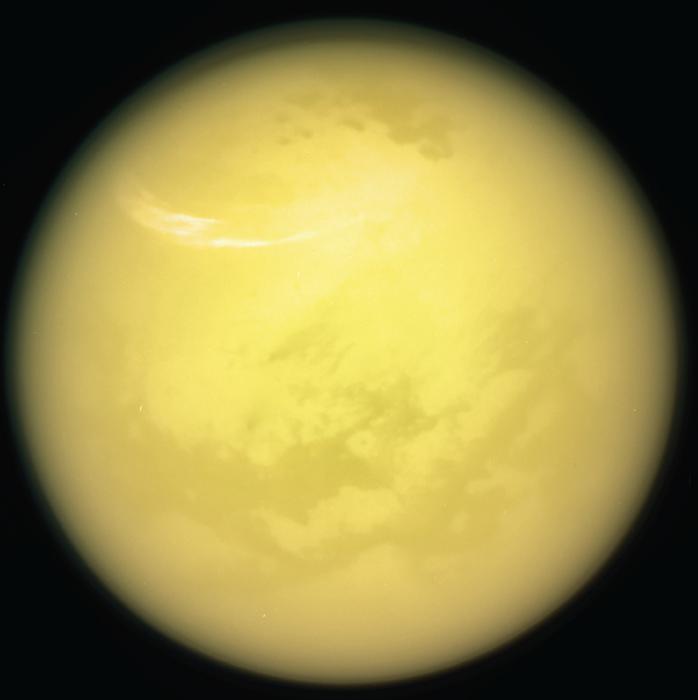

These brand new, full-color mosaics and animated movies begin with the storm’s emergence as a tiny spot in a single image December 5, 2010, and follow its subsequent growth to a storm so large it completely encircled the planet by late January 2011. The disturbance, which extends north-south approximately 9,000 miles (15,000 kilometers), grew to be the largest observed on Saturn in the past 21 years, and the largest by far ever observed on the planet from an interplanetary spacecraft. Other instruments on Cassini have detected the storm’s electrical activity and revealed it to be a convective thunderstorm. Its active convecting phase ended in late June, but the turbulent clouds it created linger in the atmosphere today.

The storm’s 200-day active period also makes it the longest-lasting planet-encircling storm ever seen on Saturn. The previous record holder was an outburst sighted in 1903, which lingered for 150 days. The large disturbance imaged 21 years ago by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope was comparable in size to the current storm. That 1990 storm lasted for only 55 days.

The collected images and movies can be seen here:

* http://ciclops.org

* http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov

* http://www.nasa.gov/cassini

They include mosaics of dozens of images stitched together and presented in true and false colors.

“The Saturn storm is more like a volcano than a terrestrial weather system,” said Andrew Ingersoll from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “The pressure builds up for many years before the storm erupts. The mystery is that there’s no rock to resist the pressure to delay the eruption for so many years.”

Cassini has taken hundreds of images of this storm as part of the imaging team’s “Saturn Storm Watch” campaign. During this effort, Cassini takes quick looks at the storm in between other scheduled observations of either Saturn or its rings and moons. The new images, together with other high-quality images collected by Cassini since 2004, allow scientists to trace back the subtle changes on the planet that preceded the storm’s formation and have revealed insights into the storm’s development, its wind speeds, and the altitudes at which its changes occur.

The storm first appeared at approximately 35° north latitude on Saturn and eventually wrapped itself around the entire planet to cover approximately 2 billion square miles (5 billion square km). The biggest disturbance heretofore witnessed by Cassini on Saturn occurred in a latitude band in the southern hemisphere called “Storm Alley” because of the prevalence of thunderstorms in this region — it lasted several months from 2009 to 2010. That storm was actually a cluster of thunderstorms, each of which lasted up to five days or so and affected only the local weather. The new northern disturbance is a single thunderstorm that raged continuously for more than 200 days and impacted almost one-fifth of the entire northern hemisphere.

“This new storm is a completely different kind of beast compared to anything we saw on Saturn previously with Cassini,” said Kunio Sayanagi from the University of California, Los Angeles. “The fact that such outbursts are episodic and keep happening on Saturn every 20 to 30 years or so is telling us something about deep inside the planet, but we are yet to figure out what it is.”

Current plans to continue the mission through 2017 will provide opportunities for Cassini to witness further changes in the planet’s atmosphere as the seasons progress to northern summer.

“It is the capability of being in orbit and able to turn a scrutinizing eye wherever it is needed that has allowed us to monitor this extraordinary phenomenon,” said Carolyn Porco from the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado. “Seven years of chasing such opportunities have already made Cassini one of the most scientifically productive planetary missions ever flown.”

These brand new, full-color mosaics and animated movies begin with the storm’s emergence as a tiny spot in a single image December 5, 2010, and follow its subsequent growth to a storm so large it completely encircled the planet by late January 2011. The disturbance, which extends north-south approximately 9,000 miles (15,000 kilometers), grew to be the largest observed on Saturn in the past 21 years, and the largest by far ever observed on the planet from an interplanetary spacecraft. Other instruments on Cassini have detected the storm’s electrical activity and revealed it to be a convective thunderstorm. Its active convecting phase ended in late June, but the turbulent clouds it created linger in the atmosphere today.

The storm’s 200-day active period also makes it the longest-lasting planet-encircling storm ever seen on Saturn. The previous record holder was an outburst sighted in 1903, which lingered for 150 days. The large disturbance imaged 21 years ago by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope was comparable in size to the current storm. That 1990 storm lasted for only 55 days.

The collected images and movies can be seen here:

* http://ciclops.org

* http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov

* http://www.nasa.gov/cassini

They include mosaics of dozens of images stitched together and presented in true and false colors.

“The Saturn storm is more like a volcano than a terrestrial weather system,” said Andrew Ingersoll from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “The pressure builds up for many years before the storm erupts. The mystery is that there’s no rock to resist the pressure to delay the eruption for so many years.”

Cassini has taken hundreds of images of this storm as part of the imaging team’s “Saturn Storm Watch” campaign. During this effort, Cassini takes quick looks at the storm in between other scheduled observations of either Saturn or its rings and moons. The new images, together with other high-quality images collected by Cassini since 2004, allow scientists to trace back the subtle changes on the planet that preceded the storm’s formation and have revealed insights into the storm’s development, its wind speeds, and the altitudes at which its changes occur.

The storm first appeared at approximately 35° north latitude on Saturn and eventually wrapped itself around the entire planet to cover approximately 2 billion square miles (5 billion square km). The biggest disturbance heretofore witnessed by Cassini on Saturn occurred in a latitude band in the southern hemisphere called “Storm Alley” because of the prevalence of thunderstorms in this region — it lasted several months from 2009 to 2010. That storm was actually a cluster of thunderstorms, each of which lasted up to five days or so and affected only the local weather. The new northern disturbance is a single thunderstorm that raged continuously for more than 200 days and impacted almost one-fifth of the entire northern hemisphere.

“This new storm is a completely different kind of beast compared to anything we saw on Saturn previously with Cassini,” said Kunio Sayanagi from the University of California, Los Angeles. “The fact that such outbursts are episodic and keep happening on Saturn every 20 to 30 years or so is telling us something about deep inside the planet, but we are yet to figure out what it is.”

Current plans to continue the mission through 2017 will provide opportunities for Cassini to witness further changes in the planet’s atmosphere as the seasons progress to northern summer.

“It is the capability of being in orbit and able to turn a scrutinizing eye wherever it is needed that has allowed us to monitor this extraordinary phenomenon,” said Carolyn Porco from the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado. “Seven years of chasing such opportunities have already made Cassini one of the most scientifically productive planetary missions ever flown.”