“By studying these supermassive stars and the shell surrounding them, we hope to learn more about how energy is transmitted in such extreme environments,” said Mubdi Rahman from the University of Toronto.

Such large nurseries of massive stars have been noticed in other galaxies, but they were so far away that all stars are often blurred together on images taken by telescopes. “This time, the massive stars are right here in our galaxy, and we can even count them individually,” Rahman said.

Studying the individual stars will require intricate measurements. The cluster of bright stars is located nearly halfway across our galaxy, 30,000 light-years away, and the line of sight is blocked by dust. “All this dust made it difficult for us to figure out what type of stars they are,” Rahman said.

“These stars are incredibly bright, yet they’re very hard to see,” Rahman said. Before the light from these stars can reach us, the intervening dust in our galaxy absorbs most of it. This makes the brightest stars in the cluster appear as dim as smaller, nearby stars. The fainter stars in the cluster appear so dim that they are not seen.

The researchers used the New Technology Telescope at the European Southern Observatory in Chile to collect whatever light they could from a few dozen stars. They measured, in detail, how much light the stars emit in each color and were finally able to confirm that at least a dozen stars in the cluster were of the most massive kind, some possibly a hundred times more massive than our Sun.

In fact, before turning a ground-based telescope toward the stars themselves, Rahman first noticed the glow from the large shell of heated gas using the WMAP satellite, which is sensitive to microwaves — between radio waves and visible light. To make an image of the gas shell being blown away and heated up, the researchers used the Spitzer satellite, which works with infrared light — between microwave and visible light.

Rahman suggested the name “Dragonfish” after comparing the infrared image of the celestial gas shell with Peter Shearer’s illustration of the deep-sea creature with the same name. The astronomical image resembles a dark, gaping mouth-like shape with teeth, two eyes, and a bright fin to the right. The “mouth” is the volume from which the gas has been cleared by the light of the stars, pushed outward to form a shell that is particularly bright in spots, corresponding to the eyes and the fin of the animal.

“We were able to see the effect of the stars on their surroundings before seeing the stars directly,” Rahman said. This would be like seeing lit faces and red cheeks from the heat of a campfire without being able to see the logs and flames themselves.

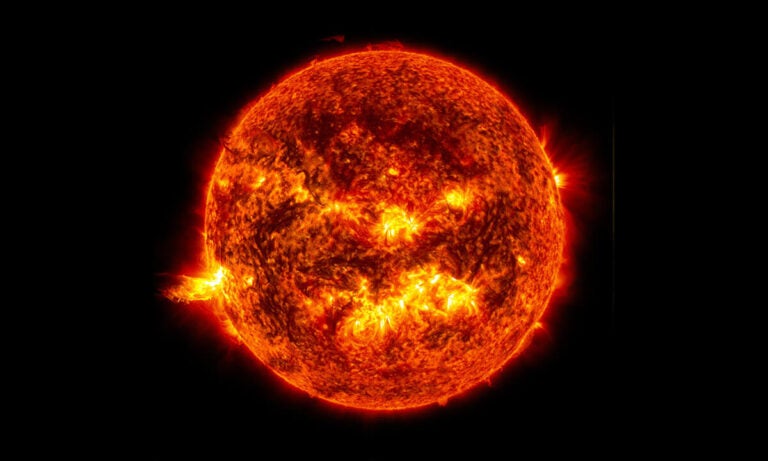

In the same way that red embers are cooler than the blue flame of a welding torch, the gas is cooler than what is heating it, and thus glows redder than the blue stars. Compared to the colors of a rainbow ranging from red to blue, most of the light emitted by the heated gas is in fact redder than red, and thus infrared — less affected by gas or dust and invisible to our naked eyes but not to appropriate telescope instruments. At the other end of the rainbow, the giant stars in the cluster are bluer than blue and emit mostly in the ultraviolet, which is blocked by dust and not visible on the image.

“But we had to make sure what was at the heart of the shell,” Rahman said. Now that the astronomers have identified several stars there as massive, they know that these stars will burn their nuclear fuel relatively quickly in astronomical terms — within a few million years, thousands of times faster than for our Sun, even though the giant blue stars contain dozens of times more fuel than our Sun.

“Still, if you thought the inside of the shell was empty, think again,” Rahman said. For each of the few hundred superstars the researchers may have spotted, there are thousands of average stars more like our Sun. When the superstars have burned through their fuel, they will explode and release metals and other heavy atoms that may help form rocky planets around smaller, quieter stars, perhaps providing the building blocks for life.

“There may be newer stars already forming in the eyes of the Dragonfish,” Rahman said. Some areas in the shell glow particularly bright, and the researchers think the gas may have been compressed enough to ignite even more stars.

The gas now in the shell is the remainder of the same gas that gave birth to the stars, and there is a lot of it — the mother shell is more massive than the cluster of its babies. But with no mother anymore to keep them reined in via its mass and gravity, all the young stars may start wandering off in all directions. “We’ve found a rebel in the group, a runaway star escaping from the group at high speed,” Rahman said. “We think the group is no longer tied together by gravity, however, how the association will fly apart is something we still don’t understand well.”

“By studying these supermassive stars and the shell surrounding them, we hope to learn more about how energy is transmitted in such extreme environments,” said Mubdi Rahman from the University of Toronto.

Such large nurseries of massive stars have been noticed in other galaxies, but they were so far away that all stars are often blurred together on images taken by telescopes. “This time, the massive stars are right here in our galaxy, and we can even count them individually,” Rahman said.

Studying the individual stars will require intricate measurements. The cluster of bright stars is located nearly halfway across our galaxy, 30,000 light-years away, and the line of sight is blocked by dust. “All this dust made it difficult for us to figure out what type of stars they are,” Rahman said.

“These stars are incredibly bright, yet they’re very hard to see,” Rahman said. Before the light from these stars can reach us, the intervening dust in our galaxy absorbs most of it. This makes the brightest stars in the cluster appear as dim as smaller, nearby stars. The fainter stars in the cluster appear so dim that they are not seen.

The researchers used the New Technology Telescope at the European Southern Observatory in Chile to collect whatever light they could from a few dozen stars. They measured, in detail, how much light the stars emit in each color and were finally able to confirm that at least a dozen stars in the cluster were of the most massive kind, some possibly a hundred times more massive than our Sun.

In fact, before turning a ground-based telescope toward the stars themselves, Rahman first noticed the glow from the large shell of heated gas using the WMAP satellite, which is sensitive to microwaves — between radio waves and visible light. To make an image of the gas shell being blown away and heated up, the researchers used the Spitzer satellite, which works with infrared light — between microwave and visible light.

Rahman suggested the name “Dragonfish” after comparing the infrared image of the celestial gas shell with Peter Shearer’s illustration of the deep-sea creature with the same name. The astronomical image resembles a dark, gaping mouth-like shape with teeth, two eyes, and a bright fin to the right. The “mouth” is the volume from which the gas has been cleared by the light of the stars, pushed outward to form a shell that is particularly bright in spots, corresponding to the eyes and the fin of the animal.

“We were able to see the effect of the stars on their surroundings before seeing the stars directly,” Rahman said. This would be like seeing lit faces and red cheeks from the heat of a campfire without being able to see the logs and flames themselves.

In the same way that red embers are cooler than the blue flame of a welding torch, the gas is cooler than what is heating it, and thus glows redder than the blue stars. Compared to the colors of a rainbow ranging from red to blue, most of the light emitted by the heated gas is in fact redder than red, and thus infrared — less affected by gas or dust and invisible to our naked eyes but not to appropriate telescope instruments. At the other end of the rainbow, the giant stars in the cluster are bluer than blue and emit mostly in the ultraviolet, which is blocked by dust and not visible on the image.

“But we had to make sure what was at the heart of the shell,” Rahman said. Now that the astronomers have identified several stars there as massive, they know that these stars will burn their nuclear fuel relatively quickly in astronomical terms — within a few million years, thousands of times faster than for our Sun, even though the giant blue stars contain dozens of times more fuel than our Sun.

“Still, if you thought the inside of the shell was empty, think again,” Rahman said. For each of the few hundred superstars the researchers may have spotted, there are thousands of average stars more like our Sun. When the superstars have burned through their fuel, they will explode and release metals and other heavy atoms that may help form rocky planets around smaller, quieter stars, perhaps providing the building blocks for life.

“There may be newer stars already forming in the eyes of the Dragonfish,” Rahman said. Some areas in the shell glow particularly bright, and the researchers think the gas may have been compressed enough to ignite even more stars.

The gas now in the shell is the remainder of the same gas that gave birth to the stars, and there is a lot of it — the mother shell is more massive than the cluster of its babies. But with no mother anymore to keep them reined in via its mass and gravity, all the young stars may start wandering off in all directions. “We’ve found a rebel in the group, a runaway star escaping from the group at high speed,” Rahman said. “We think the group is no longer tied together by gravity, however, how the association will fly apart is something we still don’t understand well.”