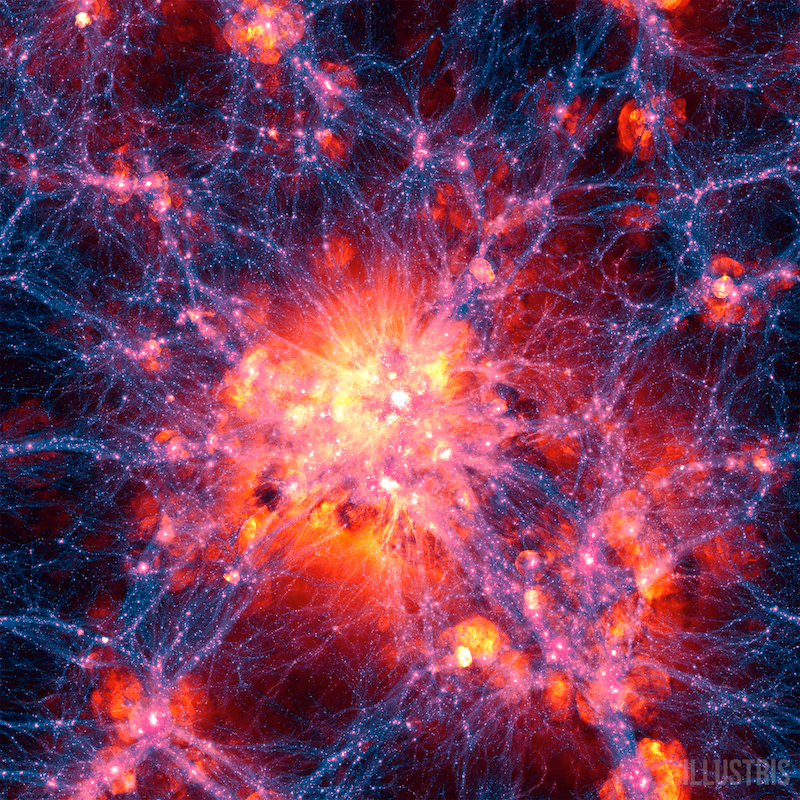

But in recent decades, astronomers have suspected that the center of our galaxy has an elongated stellar structure, or bar, that is hidden by dust and gas from easy view. Many spiral galaxies in the universe are known to exhibit such a bar through the central bulge, while other spiral galaxies are simple spirals. And astronomers ask, why? Andrea Kunder from Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO) in northern Chile and a team of colleagues have presented data that demonstrates how this bar is rotating.

A team assembled by R. Michael Rich from the University of California, Los Angeles, measured the velocity of a large sample of old red stars toward the galactic center. They did this by observing the spectra of these stars, called M giants, which allows the velocity of the star along our line of sight to be determined. During a period of four years, the scientists acquired almost 10,000 spectra with the CTIO Blanco 4-meter telescope located in the Chilean Atacama desert, resulting in the largest homogeneous sample of radial velocities with which to study the core of the Milky Way.

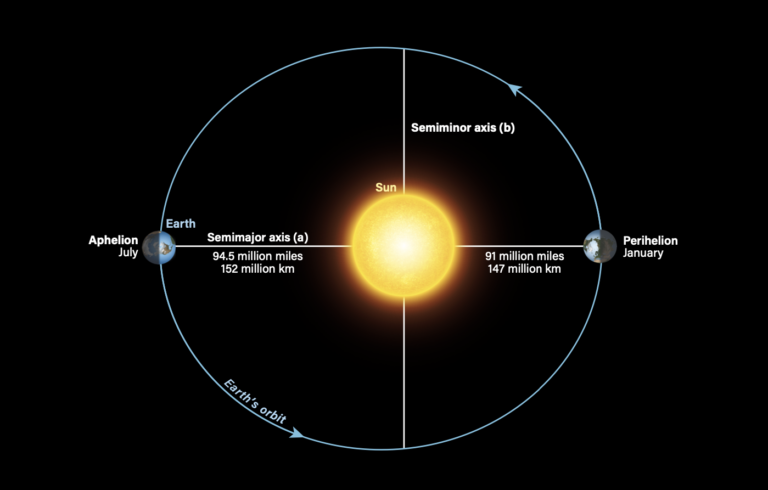

Analyzing the stellar motions confirms that the bulge in the center of our galaxy appears to consist of a massive bar with one end pointed almost in the direction of the Sun, which is rotating like a solid object. Although our galaxy rotates much like a pinwheel, with the stars in the arms of the galaxy orbiting the center, the scientists found that the rotation of the inner bar is cylindrical. This result is a large step forward in explaining the formation of the complicated central region of the Milky Way.

The full set of 10,000 spectra was compared with a computer simulation of how the bar formed from a pre-existing disk of stars. Juntai Shen of the Shanghai Observatory developed the model. The data fits the simulation extremely well and suggests that before our bar existed there was a massive disk of stars. This is in contrast to the standard picture in which our galaxy’s central region formed from the chaotic merger of gas clouds very early in the history of the universe. The implication is that gas played a role, but appears to have largely organized into a massive rotating disk that then turned into a bar due to the gravitational interactions of the stars.

The stellar spectra also allow the team to analyze the chemical composition of the stars. While all stars are composed primarily of hydrogen, with some helium, it is the trace of all the other elements in the periodic table, called “metals” by astronomers, that allow us to say something about the conditions under which the star formed. The team found that stars closest to the plane of the galaxy have a lower ratio of metals than stars farther from the plane. While this trend confirms standard views, the data cover a significant area of the bulge that can be chemically fingerprinted. By mapping how the metal content of stars varies throughout the Milky Way, astronomers can decipher star formation and evolution, just as mapping carbon dioxide concentrations in different layers of Antarctic ice reveal ancient weather patterns.

The international team of astronomers on this project has made all of their data available to other astronomers for additional analysis. They note that in the future it will be possible to measure more precise motions of these stars so that they can determine the true motion in space, not just the motion along our line of sight.

But in recent decades, astronomers have suspected that the center of our galaxy has an elongated stellar structure, or bar, that is hidden by dust and gas from easy view. Many spiral galaxies in the universe are known to exhibit such a bar through the central bulge, while other spiral galaxies are simple spirals. And astronomers ask, why? Andrea Kunder from Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO) in northern Chile and a team of colleagues have presented data that demonstrates how this bar is rotating.

A team assembled by R. Michael Rich from the University of California, Los Angeles, measured the velocity of a large sample of old red stars toward the galactic center. They did this by observing the spectra of these stars, called M giants, which allows the velocity of the star along our line of sight to be determined. During a period of four years, the scientists acquired almost 10,000 spectra with the CTIO Blanco 4-meter telescope located in the Chilean Atacama desert, resulting in the largest homogeneous sample of radial velocities with which to study the core of the Milky Way.

Analyzing the stellar motions confirms that the bulge in the center of our galaxy appears to consist of a massive bar with one end pointed almost in the direction of the Sun, which is rotating like a solid object. Although our galaxy rotates much like a pinwheel, with the stars in the arms of the galaxy orbiting the center, the scientists found that the rotation of the inner bar is cylindrical. This result is a large step forward in explaining the formation of the complicated central region of the Milky Way.

The full set of 10,000 spectra was compared with a computer simulation of how the bar formed from a pre-existing disk of stars. Juntai Shen of the Shanghai Observatory developed the model. The data fits the simulation extremely well and suggests that before our bar existed there was a massive disk of stars. This is in contrast to the standard picture in which our galaxy’s central region formed from the chaotic merger of gas clouds very early in the history of the universe. The implication is that gas played a role, but appears to have largely organized into a massive rotating disk that then turned into a bar due to the gravitational interactions of the stars.

The stellar spectra also allow the team to analyze the chemical composition of the stars. While all stars are composed primarily of hydrogen, with some helium, it is the trace of all the other elements in the periodic table, called “metals” by astronomers, that allow us to say something about the conditions under which the star formed. The team found that stars closest to the plane of the galaxy have a lower ratio of metals than stars farther from the plane. While this trend confirms standard views, the data cover a significant area of the bulge that can be chemically fingerprinted. By mapping how the metal content of stars varies throughout the Milky Way, astronomers can decipher star formation and evolution, just as mapping carbon dioxide concentrations in different layers of Antarctic ice reveal ancient weather patterns.

The international team of astronomers on this project has made all of their data available to other astronomers for additional analysis. They note that in the future it will be possible to measure more precise motions of these stars so that they can determine the true motion in space, not just the motion along our line of sight.