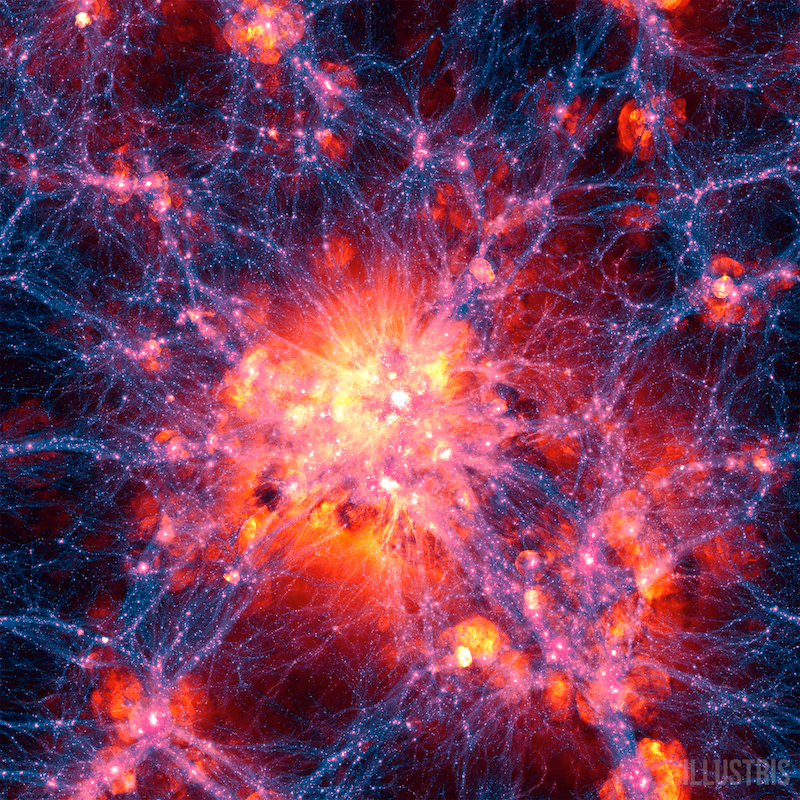

Supermassive black holes appear to have existed when the universe was young. Evidence for this comes from quasars — extremely bright objects thought to have played host to massive black holes in the early universe.

“They couldn’t just go away,” said Nicholas McConnell from the University of California at Berkeley. “So where are these black holes hiding now?”

The discovery of these two supermassive black holes, each approaching 10 billion times the mass of the Sun, is providing answers to this question.

“At this stage, it’s too early to tell whether these two black holes are a rare find or just the tip of the iceberg,” said McConnell. “In the next few years, we plan to examine a dozen or more of the largest galaxies in the local universe to look for more black holes of similar masses. Finding more will confirm that the universe once contained prime real estate for growing giant black holes.”

McConnell and his advisor and team-leader Chung-Pei Ma were joined by researchers from the University of Texas at Austin; University of Michigan in Ann Arbor; Dunlap Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics at the University of Toronto, Canada; and the National Optical Astronomy Observatory (NOAO) in Arizona.

“The boisterous quasars that we see when we look back in time at the young universe may have passed through a turbulent youth to become the quiescent giant elliptical galaxies we see today,” said Ma. “The black holes at the centers of these galaxies are no longer fed by accreting gas and have become dormant and hidden. We see them only because of their gravitational pull on nearby orbiting stars.”

The question remains whether there is a limit as to how big a black hole can get. “Larger black holes tend to live in bigger parent galaxies, so is it nature or nurture that determines how large a black hole can grow?” asked Ma.

In addition to the Gemini observations, follow-up data from the W.M. Keck and McDonald observatories supported the team’s conclusion that these black holes are record holders. “We believe that 10-billion-solar-mass black holes like these are the ultimate power sources for the distant quasars observed in the early universe, one to three billion years after the Big Bang,” said James Graham from the Canadian Dunlap Institute.

The astronomers found the black holes in NGC 3842 and NGC 4889 to be giant elliptical galaxies and the brightest members of galaxy clusters. NGC 3842 lies about 320 million light-years away in the Leo galaxy cluster, and NGC 4889 is the brightest member of the famous Coma galaxy cluster that is about 336 million light-years distant. Both of these galaxies are bright enough to spot in amateur telescopes.

McConnell adds that while the galaxies studied are relatively close, it is extremely difficult to observe the stars within about 1,000 light-years of the black hole at a distance of about 300 million light-years. Only stars orbiting in this small region surrounding the black hole are sensitive enough to the hole’s gravity to be used to determine its mass. “This means we need exquisite observing conditions and the latest technology to have any hope of seeing what’s going on around the black hole,” McConnell said.

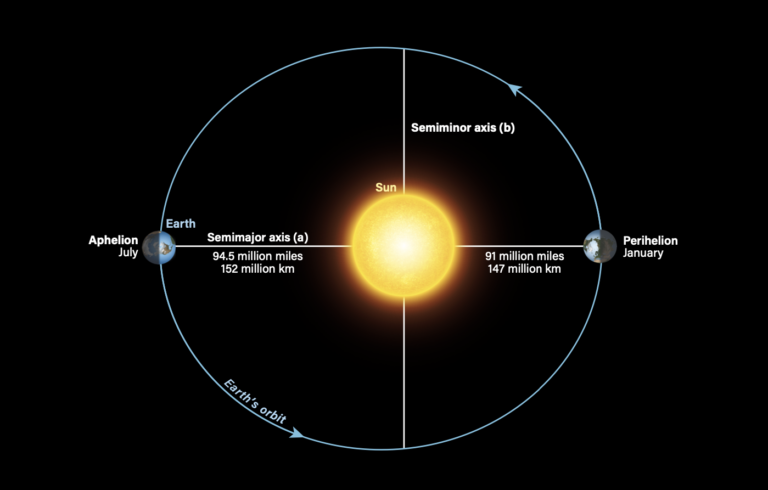

The two black holes discovered in this research are more than 2,000 times bigger than the one that resides at the center of our galaxy, which has a mass of about 4 million times that of our Sun. Team member Tod Lauer from NOAO notes that the event horizons — the region inside of which light can no longer escape — of these black holes are far larger than our solar system. Each is five to 10 times bigger than Pluto’s orbit.

Supermassive black holes appear to have existed when the universe was young. Evidence for this comes from quasars — extremely bright objects thought to have played host to massive black holes in the early universe.

“They couldn’t just go away,” said Nicholas McConnell from the University of California at Berkeley. “So where are these black holes hiding now?”

The discovery of these two supermassive black holes, each approaching 10 billion times the mass of the Sun, is providing answers to this question.

“At this stage, it’s too early to tell whether these two black holes are a rare find or just the tip of the iceberg,” said McConnell. “In the next few years, we plan to examine a dozen or more of the largest galaxies in the local universe to look for more black holes of similar masses. Finding more will confirm that the universe once contained prime real estate for growing giant black holes.”

McConnell and his advisor and team-leader Chung-Pei Ma were joined by researchers from the University of Texas at Austin; University of Michigan in Ann Arbor; Dunlap Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics at the University of Toronto, Canada; and the National Optical Astronomy Observatory (NOAO) in Arizona.

“The boisterous quasars that we see when we look back in time at the young universe may have passed through a turbulent youth to become the quiescent giant elliptical galaxies we see today,” said Ma. “The black holes at the centers of these galaxies are no longer fed by accreting gas and have become dormant and hidden. We see them only because of their gravitational pull on nearby orbiting stars.”

The question remains whether there is a limit as to how big a black hole can get. “Larger black holes tend to live in bigger parent galaxies, so is it nature or nurture that determines how large a black hole can grow?” asked Ma.

In addition to the Gemini observations, follow-up data from the W.M. Keck and McDonald observatories supported the team’s conclusion that these black holes are record holders. “We believe that 10-billion-solar-mass black holes like these are the ultimate power sources for the distant quasars observed in the early universe, one to three billion years after the Big Bang,” said James Graham from the Canadian Dunlap Institute.

The astronomers found the black holes in NGC 3842 and NGC 4889 to be giant elliptical galaxies and the brightest members of galaxy clusters. NGC 3842 lies about 320 million light-years away in the Leo galaxy cluster, and NGC 4889 is the brightest member of the famous Coma galaxy cluster that is about 336 million light-years distant. Both of these galaxies are bright enough to spot in amateur telescopes.

McConnell adds that while the galaxies studied are relatively close, it is extremely difficult to observe the stars within about 1,000 light-years of the black hole at a distance of about 300 million light-years. Only stars orbiting in this small region surrounding the black hole are sensitive enough to the hole’s gravity to be used to determine its mass. “This means we need exquisite observing conditions and the latest technology to have any hope of seeing what’s going on around the black hole,” McConnell said.

The two black holes discovered in this research are more than 2,000 times bigger than the one that resides at the center of our galaxy, which has a mass of about 4 million times that of our Sun. Team member Tod Lauer from NOAO notes that the event horizons — the region inside of which light can no longer escape — of these black holes are far larger than our solar system. Each is five to 10 times bigger than Pluto’s orbit.