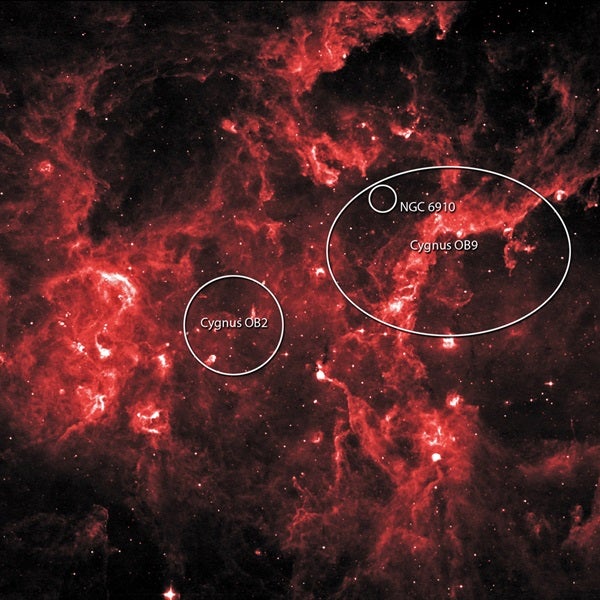

The image shows one of the most active and turbulent regions of star birth in our Milky Way Galaxy, a region called Cygnus X. The choppy cloud of gas and dust lies 4,500 light-years away in the constellation Cygnus the Swan. It is home to thousands of massive stars and many more stars around the size of our Sun or smaller. Spitzer has captured an infrared view of the entire region, bubbling with star formation.

“Spitzer captured the range of activities happening in this violent cloud of stellar birth,” said Joseph Hora from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “We see bubbles carved out by massive stars, pillars of new stars, dark filaments lined with stellar embryos, and more.”

Most stars are thought to form in huge star-forming regions like Cygnus X. Over time, the stars dissipate and migrate away from each other. It’s possible that our Sun was once packed tightly together with other, more massive stars in a similarly chaotic, though less extreme, region.

The turbulent star-forming clouds are marked with bubbles, or cavities, carved out by radiation and winds from the most massive of stars. Those massive stars tear the cloud material to shreds, terminating the formation of some stars while triggering the birth of others.

“One of the questions we want to answer is how such a violent process can lead to both the death and birth of new stars,” said Sean Carey from NASA’s Spitzer Science Center at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “We still don’t know exactly how stars form in such disruptive environments.”

Infrared data from Spitzer is helping to answer questions like these by giving astronomers a window into the dustier parts of the complex. Infrared light travels through dust, whereas visible light is blocked. For example, embryonic stars blanketed by dust pop out in the Spitzer observations. In some cases, the young stars are embedded in finger-shaped pillars of dust that line the hollowed-out cavities and point toward the central massive stars. In other cases, these stars can be seen lining dark snake-like filaments of thick dust.

Another question scientists hope to answer is how these pillars and filaments are related.

“We have evidence that the massive stars are triggering the birth of new ones in the dark filaments, in addition to the pillars, but we still have more work to do,” said Hora.

Infrared light in this image has been color-coded according to wavelength. Light of 3.6 microns is blue, 4.5-micron light is blue-green, 8.0-micron light is green, and 24-micron light is red. These data were taken before the Spitzer mission ran out of its coolant in 2009 and began its “warm” mission.