Although exotic by everyday standards, black holes are everywhere. The lowest-mass black holes are formed when massive stars reach the end of their lives, ejecting most of their material into space in a supernova explosion and leaving behind a compact core that collapses into a black hole. There are thought to be millions of these low-mass black holes distributed throughout every galaxy. Despite their ubiquity, they can be hard to detect as they do not emit light, so they are normally seen through their action on the objects around them — for example by dragging in material that then heats up in the process and emits X-rays. But despite this, the overwhelming majority of black holes have remained undetected.

In recent years, researchers have made some progress in finding ordinary black holes in binary systems by looking for the X-ray emission produced when they suck in material from their companion stars. So far, these objects have been relatively close, either in our Milky Way Galaxy or in nearby galaxies in the Local Group — a cluster of galaxies relatively near the Milky Way that includes Andromeda.

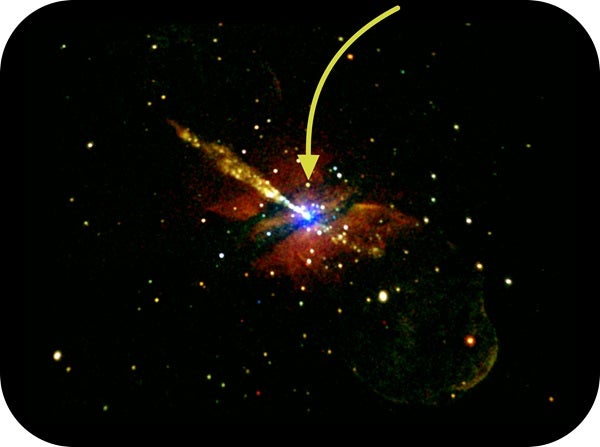

The team used the orbiting Chandra X-ray Observatory to make six 100,000-second-long exposures of Centaurus A, detecting an object with 50,000 times the X-ray brightness of our Sun. A month later, it had dimmed by more than a factor of 10 and then later by a factor of more than 100, thus becoming undetectable.

This behavior is characteristic of a low-mass black hole in a binary system during the final stages of an outburst and is typical of similar black holes in the Milky Way. It implies that the team made the first detection of a normal black hole so far away, and for the first time opens up the opportunity to characterize the black hole population of other galaxies.

“So far we’ve struggled to find many ordinary black holes in other galaxies, even though we know they are there,” said Mark Burke from the University of Birmingham, United Kingdom. “To confirm (or refute) our understanding of the evolution of stars, we need to search for these objects, despite the difficulty of detecting them at large distances. If it turns out that black holes are either much rarer or much more common in other galaxies than in our own, it would be a big challenge to some of the basic ideas that underpin astronomy.”

The group now plans to look at the more than 50 other bright X-ray sources that reside within Centaurus A, identifying them as black holes or other exotic objects, and gain at least an inkling of the nature of a further 50 less-luminous sources.