A team of astronomers, led by James Rhoads, Sangeeta Malhotra, and Pascale Hibon from Arizona State University (ASU), identified the remote galaxy after scanning a Moon-sized patch of sky with the IMACS instrument on the Magellan Telescopes at the Carnegie Institution’s Las Campanas Observatory in Chile.

The observational data reveal a faint infant galaxy located 13 billion light-years away. “This galaxy is being observed at a young age,” said Rhoads. “We are seeing it as it was in the very distant past, when the universe was a mere 800 million years old. This image is like a baby picture of this galaxy, taken when the universe was only 5 percent of its current age. Studying these very early galaxies is important because it helps us understand how galaxies form and grow.”

The galaxy, designated LAEJ095950.99+021219.1, was first spotted in the summer of 2011. The find is a rare example of a galaxy from that early epoch, and it will help astronomers make progress in understanding the process of galaxy formation. The find was enabled by the combination of the Magellan Telescopes’ tremendous light-gathering capability and exquisite image quality and by the unique ability of the IMACS instrument to obtain either images or spectra across a wide field of view.

This galaxy, like the others that Malhotra, Rhoads, and their team seek, is extremely faint and was detected by the light emitted by ionized hydrogen. The object was first identified as a candidate early-universe galaxy in a paper led by team member and former ASU researcher Hibon. The search employed a unique technique they pioneered that uses special narrow-band filters that allow a small wavelength range of light through.

A special filter fitted to the telescope camera was designed to catch light of narrow wavelength ranges, allowing the astronomers to conduct a sensitive search in the infrared wavelength range. “We have been using this technique since 1998 and pushing it to ever-greater distances and sensitivities in our search for the first galaxies at the edge of the universe,” said Malhotra. “Young galaxies must be observed at infrared wavelengths, and this is not easy to do using ground-based telescopes, since the Earth’s atmosphere itself glows and large detectors are hard to make.”

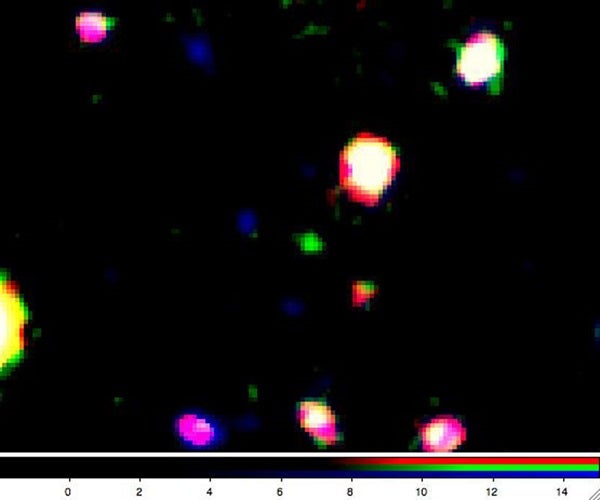

To be able to detect these distant objects, which were forming near the beginning of the universe, astronomers look for sources that have high redshifts. Astronomers refer to an object’s distance by a number called its “redshift,” which relates to how much its light has stretched to longer, redder wavelengths due to the expansion of the universe. Objects with larger redshifts are farther away and are seen further back in time. LAEJ095950.99+021219.1 has a redshift of 7. Only a handful of galaxies have confirmed redshifts greater than 7, and none of the others is as faint as LAEJ095950.99+021219.1.

“We have used this search to find hundreds of objects at somewhat smaller distances,” said Rhoads. “We have found several hundred galaxies at redshift 4.5, several at redshift 6.5, and now at redshift 7 we have found one. We’ve pushed the experiment’s design to a redshift of 7 — it’s the most distant we can do with well-established, mature technology, and it’s about the most distant where people have been finding objects successfully up to now.”

“With this search, we’ve not only found one of the furthest galaxies known, but also the faintest confirmed at that distance,” said Malhotra. “Up to now, the redshift 7 galaxies we know about are literally the top 1 percent of galaxies. What we’re doing here is to start examining some of the fainter ones — thing that may better represent the other 99 percent.”

Resolving the details of objects that are far away is challenging, which is why images of distant young galaxies such as this one appear small, faint, and blurry.

“As time goes by, these small blobs which are forming stars, they’ll dance around each other, merge with each other, and form bigger and bigger galaxies,” said Malhotra. “Somewhere halfway through the age of the universe they start looking like the galaxies we see today — and not before. Why, how, when, where that happens is a fairly active area of research.”