Galaxy HDF850.1 was discovered in 1998. It is famous for producing new stars at a rate that is near incredible even on astronomical scales — a combined mass of a thousand Suns per year. For comparison, an ordinary galaxy such as ours produces no more than one solar mass’ worth of new stars per year. Yet, for the past fourteen years, HDF850.1 has remained strangely elusive — its location in space, specifically its distance from Earth, is the subject of many studies, but ultimately unknown. How was that possible?

The “Hubble Deep Field,” where HDF850.1 is located, is a region in the sky that affords an almost unparalleled view into the deepest reaches of space. It was first studied extensively using the Hubble Space Telescope. Yet observations using visible light only reveal part of the cosmic picture, and astronomers were quick to follow up at different wavelengths. In the late 1990s, astronomers using the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope on Hawaii surveyed the region using submillimeter radiation. This type of radiation, with wavelengths between a few tenths of a millimeter and a millimeter, is particularly suitable for detecting cool clouds of gas and dust.

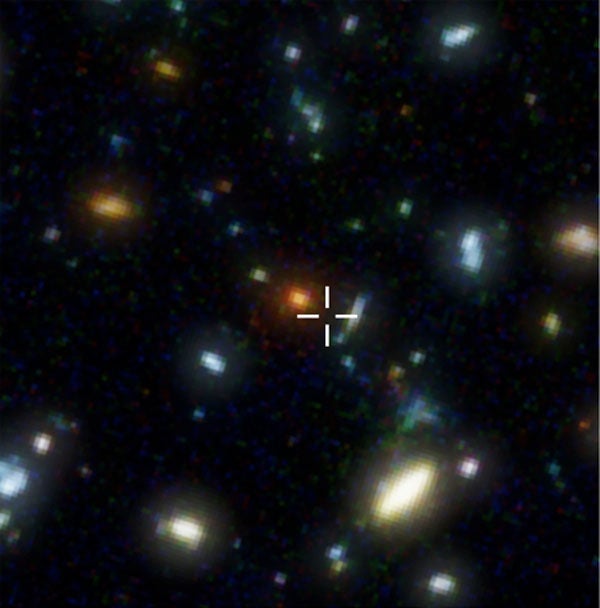

The researchers were taken by surprise when they realized that HDF850.1 was the brightest source of submillimeter emission in the field by far, a galaxy that was evidently forming as many stars as all the other galaxies in the Hubble Deep Field combined — and which was completely invisible in the observations of the Hubble Space Telescope!

“The galaxy’s invisibility is no great mystery,” said Walter. “Stars form in dense clouds of gas and dust. These dense clouds are opaque to visible light, hiding the galaxy from sight. Submillimeter radiation passes through the dense dust clouds unhindered, showing what is inside. But the lack of data from all but a very narrow range of the spectrum made it very difficult to determine the galaxy’s redshift, and thus its place in cosmic history.”

Now, an international group of researchers led by Walter has managed to solve the mystery. Taking advantage of recent upgrades to the IRAM interferometer on the Plateau de Bure in the French Alps, which combines six radio antennas that then act as a gigantic millimeter telescope, they identified the characteristic features — spectral lines — necessary for an accurate distance measurement. “It is the availability of more powerful and sensitive instruments recently installed on the IRAM interferometer that allowed us to detect these weak lines in HDF850.1, and finally find what we had been unsuccessfully looking for during the past 14 years,” said Pierre Cox from IRAM.

The result is a surprise: The galaxy is at a distance of 12.5 billion light-years from Earth. We see it as it was 12.5 billion years ago, at a time when the universe itself was only 1.1 billion years old. HDF850.1’s intense star-forming activity thus belongs to an early period of cosmic history when the universe was less than 10 percent of its current age.

A combination with observations obtained at the National Science Foundation’s Karl Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) then revealed that a large fraction of the galaxy’s mass is in the form of molecules — the raw material for future stars. The fraction is much higher than what is found in galaxies in the local universe.

Once the distance was known, the researchers were also able to put the galaxy into context. Using additional data from published and unpublished surveys, they were able to show that the galaxy is part of what appears to be an early form of galaxy cluster — one of only two such clusters known to date.

The new work highlights the importance of future, more powerful interferometers operating at millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths. Both NOEMA, the future extension of the Plateau de Bure interferometer, and ALMA, a new interferometer array currently being built by an international consortium in the Atacama desert in Chile, will cover these wavelengths in unprecedented detail. They should allow for distance determinations and more detailed study of many more galaxies, invisible at optical wavelengths that were actively forming stars in the early universe.