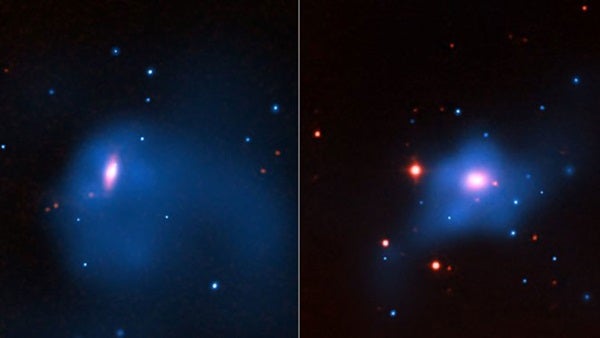

The mass of a giant black hole at the center of a galaxy typically is a tiny fraction — about 0.2 percent — of the mass contained in the bulge, or region of densely packed stars, surrounding it. The targets of the latest Chandra study, galaxies NGC 4342 and NGC 4291, have black holes 10 to 35 times more massive than they should be compared to their bulges. The new observations with Chandra show the halos, or massive envelopes of dark matter in which these galaxies reside, also are overweight.

This study suggests that the two supermassive black holes and their evolution are tied to their dark matter halos and did not grow in tandem with the galactic bulges. In this view, the black holes and dark matter halos are not overweight, but the total mass in the galaxies is too low.

“This gives us more evidence of a link between two of the most mysterious and darkest phenomena in astrophysics — black holes and dark matter — in these galaxies,” said Akos Bogdan from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

NGC 4342 and NGC 4291 are close to Earth in cosmic terms, at distances of 75 million and 85 million light-years, respectively. Astronomers had known from previous observations that these galaxies host black holes with relatively large masses, but they are not certain what is responsible for the disparity. Based on the new Chandra observations, however, they are able to rule out a phenomenon known as tidal stripping.

Tidal stripping occurs when some of a galaxy’s stars are stripped away by gravity during a close encounter with another galaxy. If such tidal stripping had taken place, the halos mostly would have been missing. Because dark matter extends farther away from the galaxies, it is more loosely tied to them than the stars and more likely to be pulled away.

To rule out tidal stripping, astronomers used Chandra to look for evidence of hot X-ray-emitting gas around the two galaxies. Because the pressure of hot gas — estimated from X-ray images — balances the gravitational pull of all the matter in the galaxy, the new Chandra data can provide information about the dark matter halos. The hot gas was distributed widely around NGC 4342 and NGC 4291, implying that each galaxy has an unusually massive dark matter halo and that tidal stripping is unlikely.

“This is the clearest evidence we have, in the nearby universe, for black holes growing faster than their host galaxy,” said Bill Forman from the CfA. “It’s not that the galaxies have been compromised by close encounters, but instead they had some sort of arrested development.”

How can the mass of a black hole grow faster than the stellar mass of its host galaxy? The study’s authors suggest a large concentration of gas spinning slowly in the galactic center is what the black hole consumes very early in its history. It grows quickly, and as it grows, the amount of gas it can accrete, or swallow, increases along with the energy output from the accretion. After the black hole reaches a critical mass, outbursts powered by the continued consumption of gas prevent cooling and limit the production of new stars.

“It’s possible that the supermassive black hole reached a hefty size before there were many stars at all in the galaxy,” said Bogdan. “That is a significant change in our way of thinking about how galaxies and black holes evolve together.”