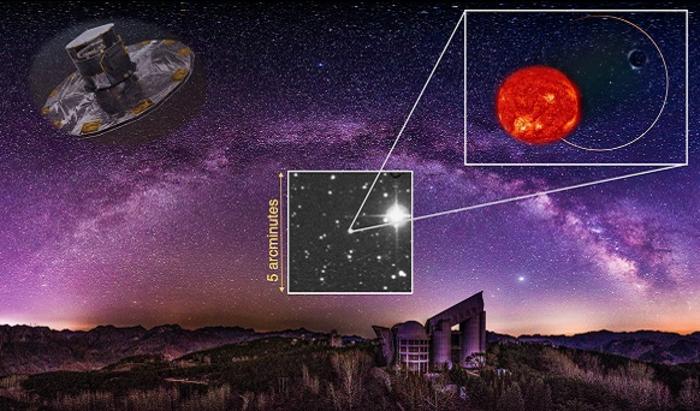

The young star, V1647 Orionis, first made news in early 2004 when it erupted and lit up McNeil’s Nebula, located 1,300 light-years away in a region of active star formation within the Orion constellation. The initial outburst died down in early 2006, but then V1647 Ori erupted again in 2008 and has since remained bright.

More recently, astronomers combined 11 observations of V1647 Ori from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, the Japan-led Suzaku satellite, and the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton to determine the source of the high-energy emission. The team began monitoring the star shortly after its eruption in 2004 and continued to keep watch through 2010, a period covering both eruptions.

Strong similarities among X-ray light curves captured over this six-year period allowed Kenji Hamaguchi from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, to identify cyclic X-ray variations. Hamaguchi and the rest of the team determined that the star is rotating once per day, making V1647 among the youngest stars whose spin has been determined using an X-ray-based technique.

“The observations give us a look inside the cradle at a very young star,” said Joel Kastner from the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) in New York. “It’s as though we’re able to see its beating heart. We’re actually able to watch it rotate. We caught the star at a point where it is rotating so fast as it gains material that it’s barely able to hold itself together. It’s rotating at near break-up speed.”

The team identified V1647 Ori as a protostar in formation. “Based on infrared studies, we suspect that this protostar is no more than a million years old, and probably much younger,” Hamaguchi said.

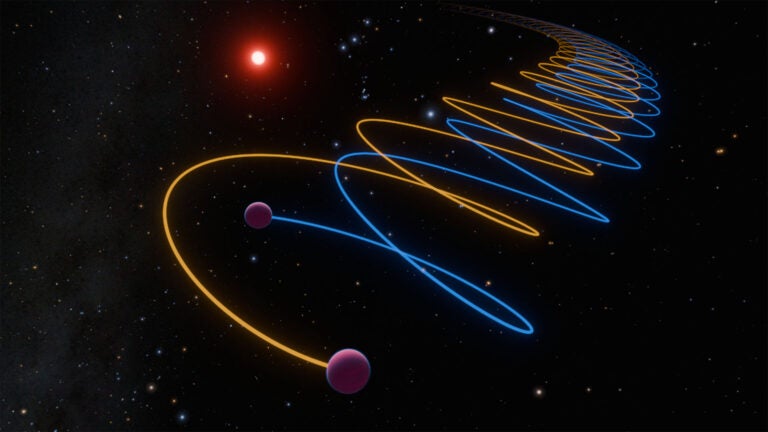

V1647 Ori presently feeds on gas channeled from a surrounding disk and will likely continue to do so — though not nearly so rapidly — for millions of years. At that point, it finally will be able to generate its own energy by fusing hydrogen into helium in its core like the Sun and other mature stars.

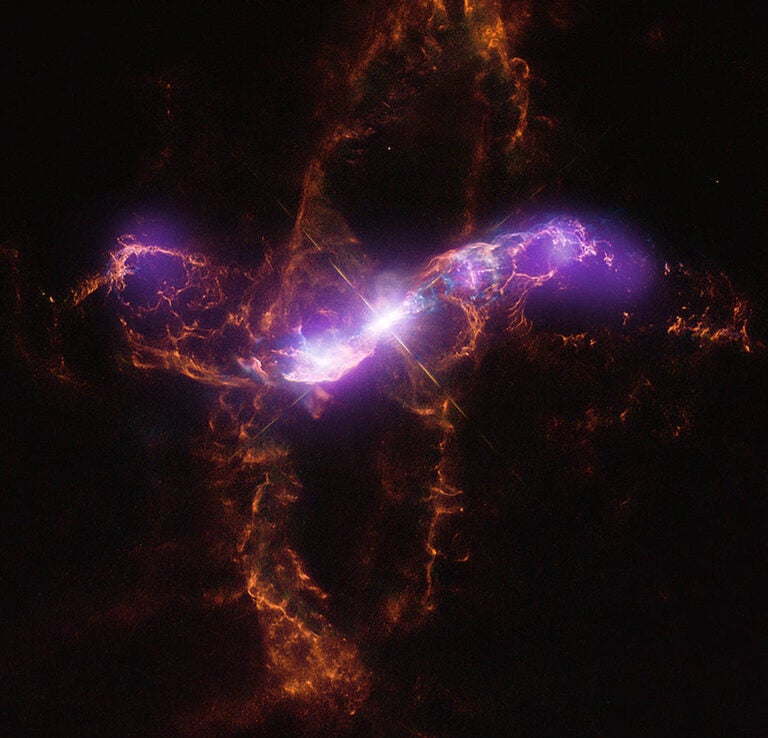

Hamaguchi’s analysis focused on repetitive behavior found in the data from all three of the X-ray observatories. By combining data, he pieced together a picture showing the daily rotation of two X-ray-emitting spots on V1647 Ori that are thousands of times hotter than the rest of the star.

The hot spots are located at opposite sides of the star, with the southerly one five times brighter than its companion. Each spot is about the diameter of the Sun. In comparison, the low density of V1647 Ori bloats the star itself to nearly five times the size of the Sun.

“We think these spots are showing us X-ray-emitting regions that are very tightly constrained to a couple positions on the star by magnetic fields,” said Kastner. “For six years, through two different eruptions, we’ve seen it rotate like this. That means the magnetic field configuration — the overall geometry between the disk and the star — is very stable. At the same time, the local disruption of magnetic fields probably generates the X-rays.”

“One attractive possibility for driving such high-speed matter involves magnetic fields that are undergoing a continual cycle of shearing and reconnection in mass accretion,” said David Weintraub from Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee.

In this picture, X-ray outbursts result from interplay of the magnetic fields belonging to the star and the disk. The star spins faster than the disk and winds up the magnetic fields until they snap like rubber bands. The pent up energy creates a powerful blast when the tangled magnetic fields fall back into place. The process, called magnetic reconnection, also powers X-ray flares on the Sun.

During the outbursts, the star’s luminosity varied at optical and infrared wavelengths. The astronomers associated this to changes in the protostar’s main energy source, the inflow of matter onto the star. Because changes in the X-ray brightness of V1647 Ori closely followed those in the optical and infrared, the team established that its higher-energy emission is also closely linked to accretion.

“V1647 Ori gave us the first direct evidence that a protostar surges in X-ray activity as its rate of mass accretion rises,” said Nicolas Grosso the Strasbourg Astronomical Observatory in France.

The finding that an accretion burst could be accompanied by a surge of high-energy X-rays during the formation of a young star was originally announced by essentially the same study team, led by Kastner, in 2004. At that time, the team first argued that X-rays emitted by V1647 Ori were coming from material falling onto the star from a surrounding disk.

Up until then, the more widely accepted mechanism for producing X-rays from protostars was thought to be via coronae that are far more powerful than the Sun’s, Kastner said. Signatures in X-ray observations of a handful of stars in formative stages had led to the hunch that accretion might also contribute to or even dominate protostellar X-ray emission. The eruptions of V1647 Ori and a few other young stars that were accompanied by elevated X-ray emission levels have since underscored this connection, Kastner said.

“The exciting and unexpected thing about our fresh look at the whole set of X-ray data for V1647 Ori is that this is the first time we’ve seen a star in such an early stage of formation with a regular rotation that you can measure in X-rays,” Kastner said.

Kastner and team hope to confirm the X-ray study’s findings at infrared wavelengths using NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope.