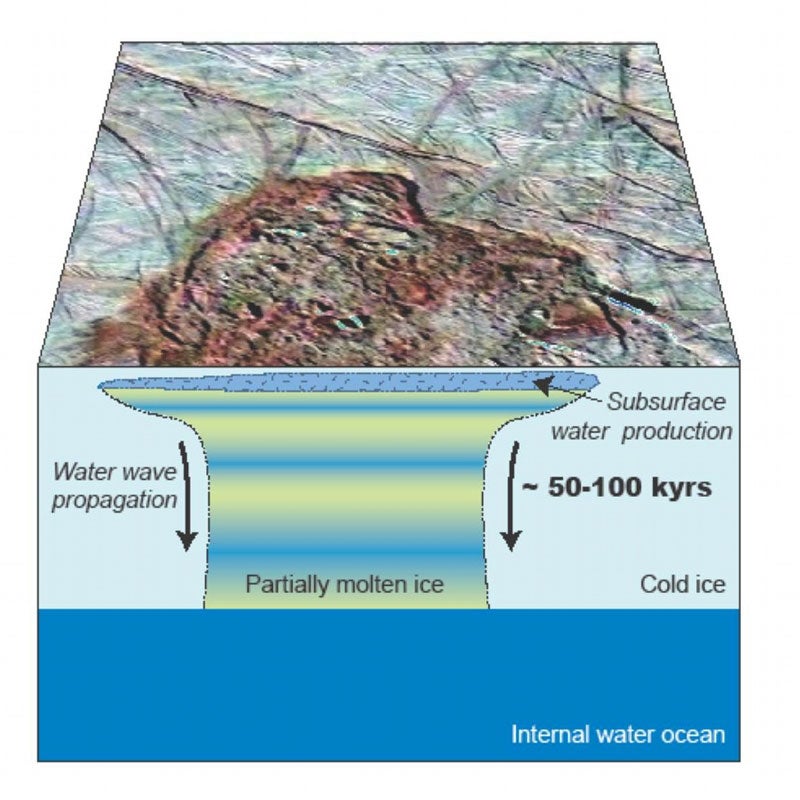

Europa is mainly made from rock and iron, with a water shell around 60 miles (100 kilometers) deep beneath a crust of solid ice. The ocean is warmed sufficiently to maintain its liquid state by heat produced as a byproduct of gravitational pulling to-and-fro from Jupiter.

Pockets of liquid water could be tantalizingly close to the surface. However, Kalousová from the University of Nantes and Charles University in Prague believes these would be short-lived. “A global water ocean may be present, but relatively deep below the surface — around 25 to 50 kilometers [15 to 30 miles],” she said. “There could be areas of liquid water at much shallower depths, say around 5 kilometers [3 miles], but these would only exist for a few tens of thousands of years before migrating downwards.”

Kalousová reached these conclusions by mathematically modeling mixtures of liquid water and solid ice under different conditions. She found that due to factors such as density and viscosity differences, liquid water migrates rapidly downwards through partially molten ice and eventually reaches the subsurface ocean.

Other locations in our solar system may be analyzed using this work. “As well as helping us to better understand Europa’s water cycle, this research could provide insight into icy moons that are geologically active, such as Enceladus,” Kalousová said, “and worlds that have cycles connecting the interior with a surface atmosphere, such as Titan.”