“These terrific results from the Mini-RF team contribute to the evolving story of water on the Moon,” says LRO’s deputy project scientist, John Keller of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “Several of the instruments on LRO have made unique contributions to this story, but only the radar penetrates beneath the surface to look for signatures of blocky ice deposits.”

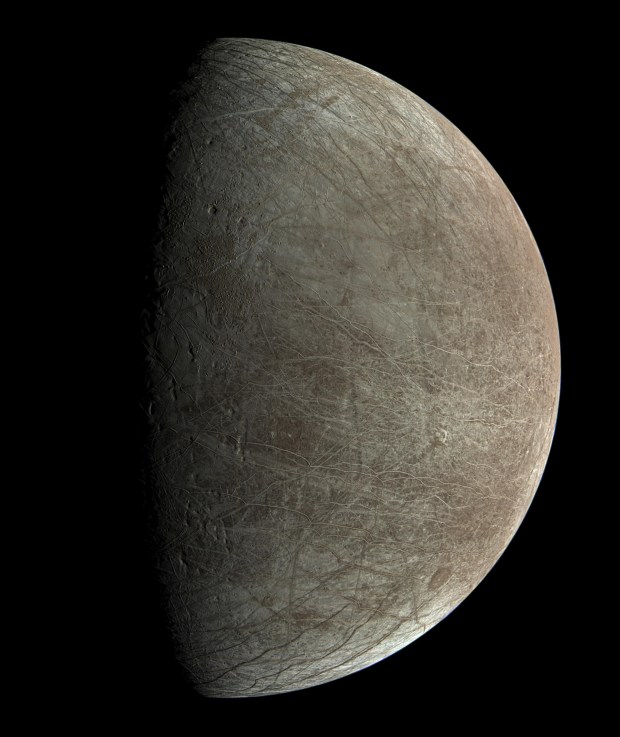

These are the first orbital radar measurements of Shackleton Crater, a high-priority target for future exploration. The observations indicate an enhanced radar polarization signature, which is consistent with the presence of small amounts of ice in the rough inner wall slopes of the crater.

“The interior of this crater lies in permanent shadow and is a ‘cold trap’ — a place cold enough to permit ice to accumulate,” says Mini-RF principal investigator Ben Bussey of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. “The radar results are consistent with the interior of Shackleton containing a few percent ice mixed into the dry lunar soil.”

These findings support the long-recognized possibility that areas of permanent shadow inside polar impact craters are sites of the potential accumulation of water. Numerous lines of evidence from recent spacecraft observations have revised the view that the lunar surface is a completely dry, inhospitable landscape. Thin films of water and hydroxyl have been detected across the lunar surface using several space-borne near-infrared spectrometers. Additionally, orbital neutron measurements indicate elevated levels of near‐surface hydrogen in the polar regions; if in the form of water, this hydrogen would represent an average ice concentration of about 1.5 percent by weight in the polar regions.

The Shackleton findings also are consistent with those of the recent LCROSS spacecraft’s controlled collision with a nearby permanently shadowed polar region near the lunar south pole, which revealed evidence for water in the plume kicked up by its impact. A radar instrument flown on India’s Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft in 2009 found evidence for ice deposits in craters at the lunar north pole. Measurements of the albedo (surface reflectance) inside Shackleton Crater using LRO’s laser altimeter and far‐ultraviolet detector are also consistent with the presence of a small amount of ice.

“Inside the crater, we don’t see evidence for glaciers like on Earth,” says Thomson. “Glacial ice has a whopping radar signal, and these measurements reveal a much weaker signal consistent with rugged terrain and limited ice.”

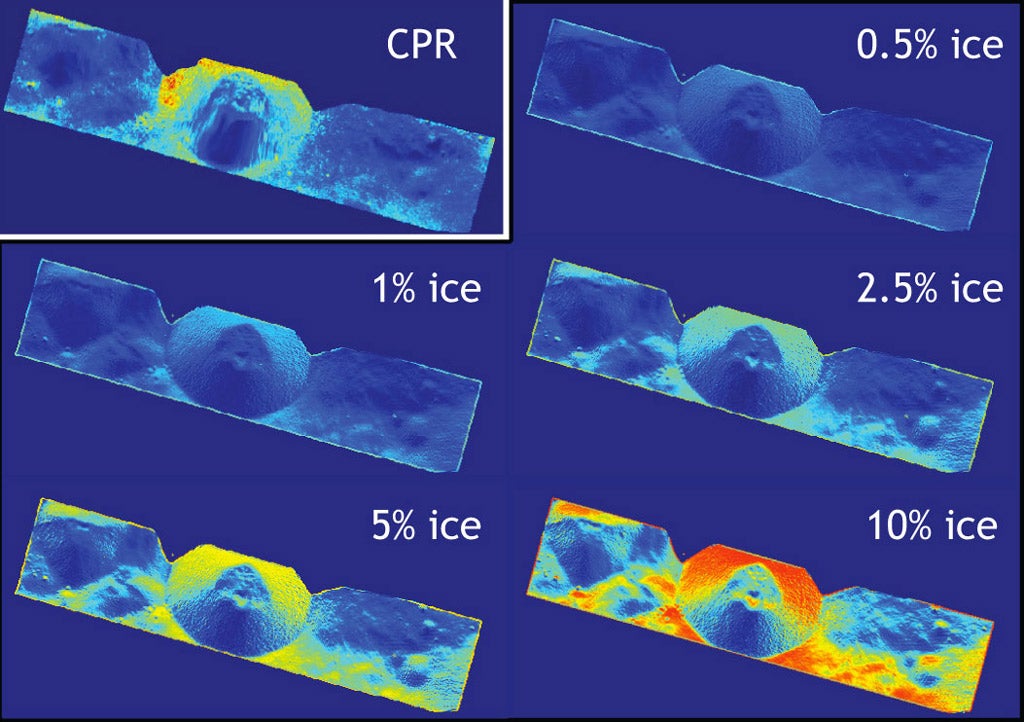

The radar measurements of Shackleton Crater were made during three separate observations between December 2009 and June 2010. Radar illuminates shadowed regions and can detect deposits of water or ice, which have a distinctive radar polarization signature compared to the surrounding material. In addition, radar penetrates the terrain to depths of a meter or two and can measure water or ice buried beneath the surface. Radar measurements of Shackleton Crater place an upper bound on the ice content of the uppermost meter of loose material of the crater’s walls at between 5 and 10 percent ice by weight.

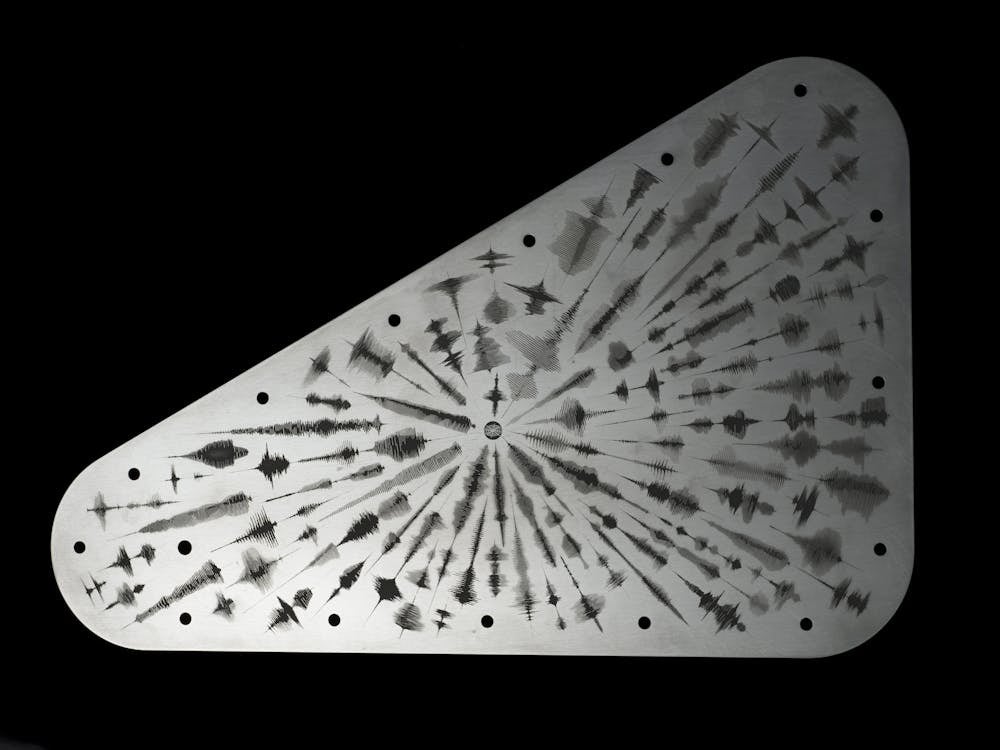

“We are following up these tantalizing results with additional observations,” says Bussey. “Mini-RF is currently acquiring new bistatic radar images of the Moon using a signal transmitted by the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico. These bistatic images will help us distinguish between surface roughness and ice, providing further unique insights into the locations of volatile deposits.”