Aided by volunteers using the Planethunters.org website, a Yale-led international team of astronomers identified and confirmed discovery of the phenomenon — called a circumbinary planet in a four-star system.

Only six planets are known to orbit two stars, according to researchers, and none of these are orbited by distant stellar companions.

“Circumbinary planets are the extremes of planet formation,” said Meg Schwamb from Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. “The discovery of these systems is forcing us to go back to the drawing board to understand how such planets can assemble and evolve in these dynamically challenging environments.”

Dubbed PH1, the planet was first identified by citizen scientists participating in Planet Hunters, a Yale-led program that enlists the public to review astronomical data from NASA’s Kepler spacecraft for signs of planets. It is the project’s first confirmed planet.

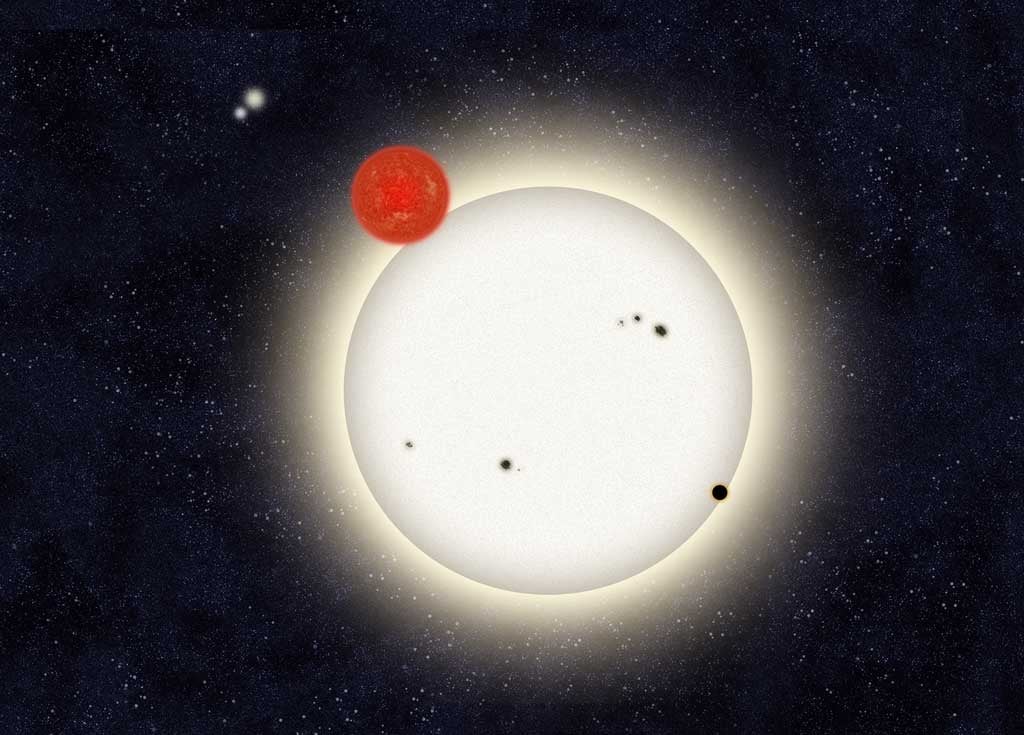

The volunteers, Kian Jek of San Francisco, California, and Robert Gagliano of Cottonwood, Arizona, spotted faint dips in light caused by the planet as it passed in front of its parent stars, a common method of finding extrasolar planets. Schwamb led the team of professional astronomers that confirmed the discovery and characterized the planet, following observations from the Keck telescopes on Mauna Kea, Hawaii. PH1 is a gas giant with a radius about 6.2 times that of Earth, making it a bit bigger than Neptune.

“Planet Hunters is a symbiotic project, pairing the discovery power of the people with follow-up by a team of astronomers,” said Debra Fischer of Yale. “This unique system might have been entirely missed if not for the sharp eyes of the public.”

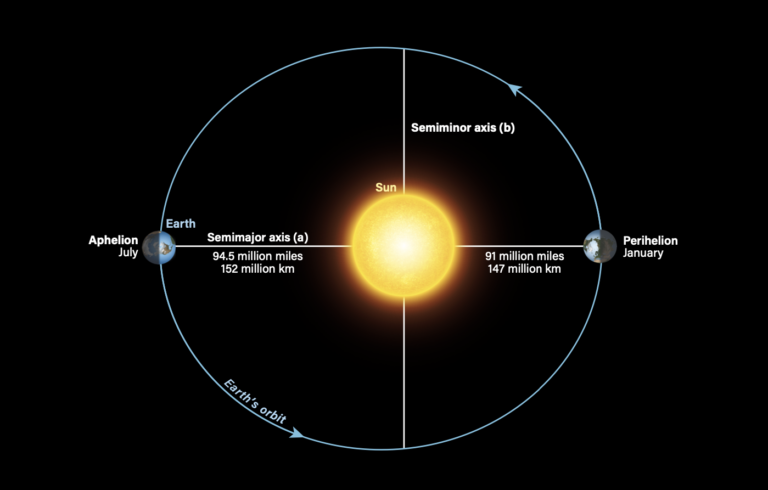

PH1 orbits outside the 20-day orbit of a pair of eclipsing stars that are 1.5 and 0.41 times the mass of the Sun. It revolves around its host stars roughly every 138 days. Beyond the planet’s orbit at about 1,000 astronomical units — roughly 1,000 times the distance between Earth and the Sun — is a second pair of stars orbiting the planetary system.

“The thousands of people who are involved with Planet Hunters are performing a valuable service,” said Jerome Orosz from San Diego State University. “Many of the automated techniques used to find interesting features in the Kepler data don’t always work as efficiently as we would like. The hard work of the Planet Hunters helps ensure that important discoveries are not falling through the cracks.”

Gagliano, one of the two citizen scientists involved in the discovery, said he was “absolutely ecstatic to spot a small dip in the eclipsing binary star’s light curve from the Kepler telescope, the signature of a potential new circumbinary planet, Tatooine. It’s a great honor to be a Planet Hunter, citizen scientist, and work hand in hand with professional astronomers, making a real contribution to science.”

“It still continues to astonish me how we can detect, let alone glean so much information, about another planet thousands of light-years away just by studying the light from its parent star,” said Jek.

Aided by volunteers using the Planethunters.org website, a Yale-led international team of astronomers identified and confirmed discovery of the phenomenon — called a circumbinary planet in a four-star system.

Only six planets are known to orbit two stars, according to researchers, and none of these are orbited by distant stellar companions.

“Circumbinary planets are the extremes of planet formation,” said Meg Schwamb from Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. “The discovery of these systems is forcing us to go back to the drawing board to understand how such planets can assemble and evolve in these dynamically challenging environments.”

Dubbed PH1, the planet was first identified by citizen scientists participating in Planet Hunters, a Yale-led program that enlists the public to review astronomical data from NASA’s Kepler spacecraft for signs of planets. It is the project’s first confirmed planet.

The volunteers, Kian Jek of San Francisco, California, and Robert Gagliano of Cottonwood, Arizona, spotted faint dips in light caused by the planet as it passed in front of its parent stars, a common method of finding extrasolar planets. Schwamb led the team of professional astronomers that confirmed the discovery and characterized the planet, following observations from the Keck telescopes on Mauna Kea, Hawaii. PH1 is a gas giant with a radius about 6.2 times that of Earth, making it a bit bigger than Neptune.

“Planet Hunters is a symbiotic project, pairing the discovery power of the people with follow-up by a team of astronomers,” said Debra Fischer of Yale. “This unique system might have been entirely missed if not for the sharp eyes of the public.”

PH1 orbits outside the 20-day orbit of a pair of eclipsing stars that are 1.5 and 0.41 times the mass of the Sun. It revolves around its host stars roughly every 138 days. Beyond the planet’s orbit at about 1,000 astronomical units — roughly 1,000 times the distance between Earth and the Sun — is a second pair of stars orbiting the planetary system.

“The thousands of people who are involved with Planet Hunters are performing a valuable service,” said Jerome Orosz from San Diego State University. “Many of the automated techniques used to find interesting features in the Kepler data don’t always work as efficiently as we would like. The hard work of the Planet Hunters helps ensure that important discoveries are not falling through the cracks.”

Gagliano, one of the two citizen scientists involved in the discovery, said he was “absolutely ecstatic to spot a small dip in the eclipsing binary star’s light curve from the Kepler telescope, the signature of a potential new circumbinary planet, Tatooine. It’s a great honor to be a Planet Hunter, citizen scientist, and work hand in hand with professional astronomers, making a real contribution to science.”

“It still continues to astonish me how we can detect, let alone glean so much information, about another planet thousands of light-years away just by studying the light from its parent star,” said Jek.