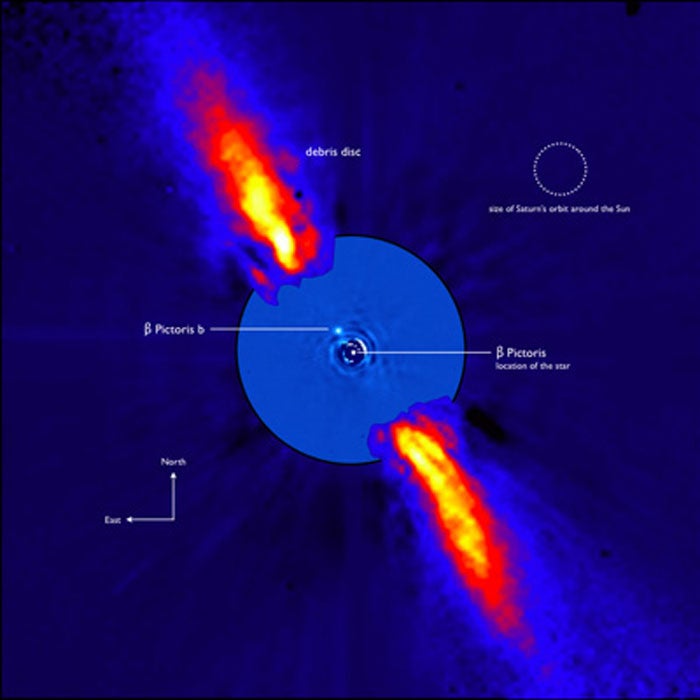

Twelve-million-year-old Beta Pictoris resides just 63 light-years from Earth and hosts a gas giant planet along with a dusty debris disk that could, in time, evolve into a torus of icy bodies much like the Kuiper Belt found outside the orbit of Neptune in our solar system. Thanks to the unique observing capabilities of Herschel, the composition of the dust in the cold outskirts of the Beta Pictoris system has been determined for the first time.

Of particular interest was the mineral olivine, which crystallizes out of the protoplanetary disk material close to newborn stars and is eventually incorporated into asteroids, comets, and planets. “As far as olivine is concerned, it comes in different ‘flavors,’” said Ben de Vries from KU Leuven in Belgium. “A magnesium-rich variety is found in small and primitive icy bodies like comets, whereas iron-rich olivine is typically found in large asteroids that have undergone more heating, or processing.” Herschel detected the pristine magnesium-rich variety in the Beta Pictoris system at 15–45 astronomical units (AU) from the star, where temperatures are around –310° Fahrenheit (–190° Celsius). For comparison, Earth lies at 1 AU from our Sun, and the solar system’s Kuiper Belt extends from the orbit of Neptune at about 30 AU out to 50 AU from the Sun.

The “radial mixing” transport mechanism is known from models of the evolution of swirling protoplanetary disks as they condense around new stars. The mixing is stimulated in varying amounts by winds and heat from the central star pushing materials away, along with temperature differences and turbulent motion created in the disk during planet formation. “Our findings are an indication that the efficiency of these transport processes must have been similar between the young solar system and within the Beta Pictoris system, and that these processes are likely independent of the detailed properties of the system,” said de Vries.

Indeed, Beta Pictoris is more than 1.5 times the mass of our Sun, eight times as bright, and its planetary system architecture is different from that of our solar system today.

“Thanks to Herschel, we were able to measure the properties of pristine material left over from the initial planet-building process in another solar system with a precision that is comparable to what we could achieve in the laboratory if we had the material here on Earth,” said Göran Pilbratt from ESA.