The nature and diversity of the progenitor star or progenitor system of core-collapse supernovae is an important and open question in the field of astrophysics. It is believed that most massive stars explode when the stars become red supergiants or, alternatively, compact blue sun — so-called Wolf-Rayet stars. Recent detections of yellow supergiant stars as possible progenitors of supernovae have posed serious questions on our understanding of the evolution of massive stars.

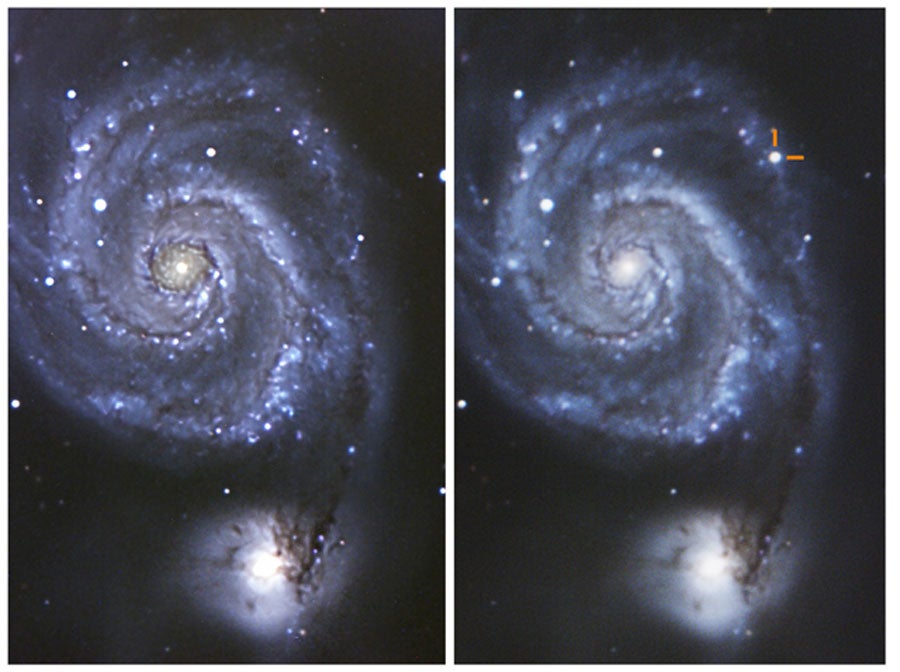

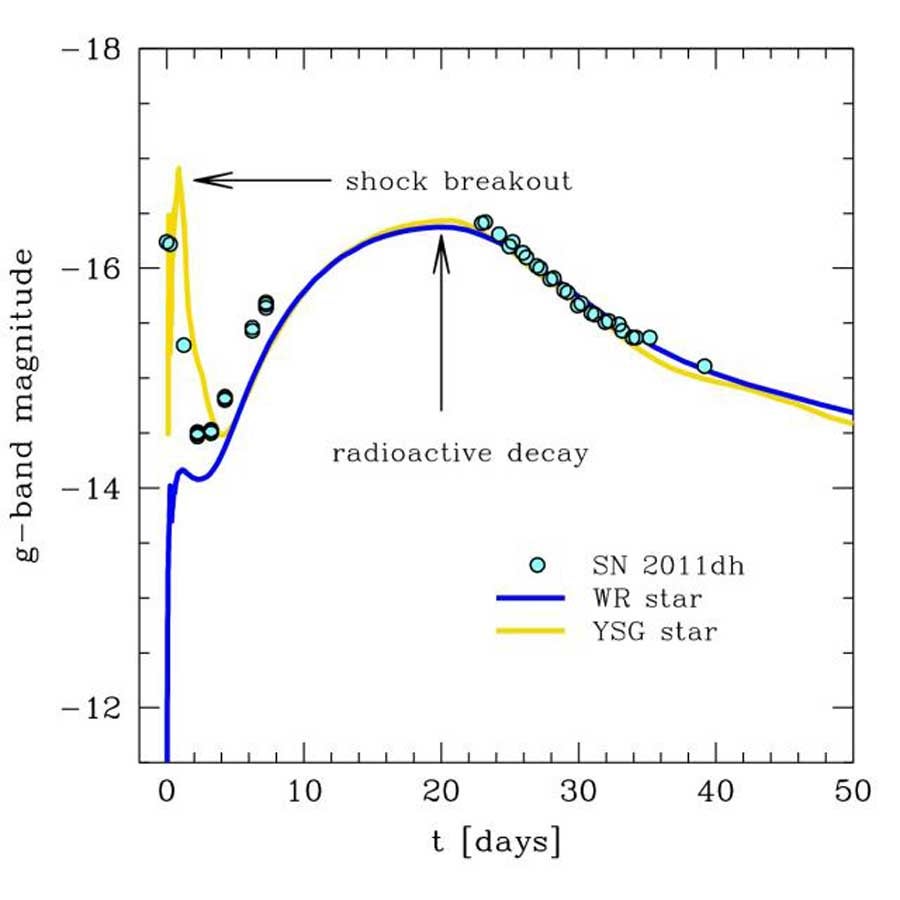

By searching through archival images obtained with the Hubble Space Telescope before the supernova explosion, two groups of astronomers independently detected a source at a location closely matching that of the supernova. Photometry of this pre-supernova source is compatible with a YSG star. If it is, indeed, the progenitor of the supernova, the question arises as to how such a star would undergo an explosion. Stellar evolution models predict that stars massive enough to produce a supernova explosion by core collapse should end their lives as red supergiants for the lower mass range or as a compact blue star for the larger masses. The YSG phase is an intermediate, short-lived stage in evolutionary models of single stars, during which no supernova explosion is expected to occur. Moreover, based on early optical emission and radio observations of SN 2011dh, some scientists claimed that the actual progenitor must have been a compact object. Therefore, the detected YSG star could have been a companion of the exploded star, or even an unrelated object that matched the projected supernova location by chance.

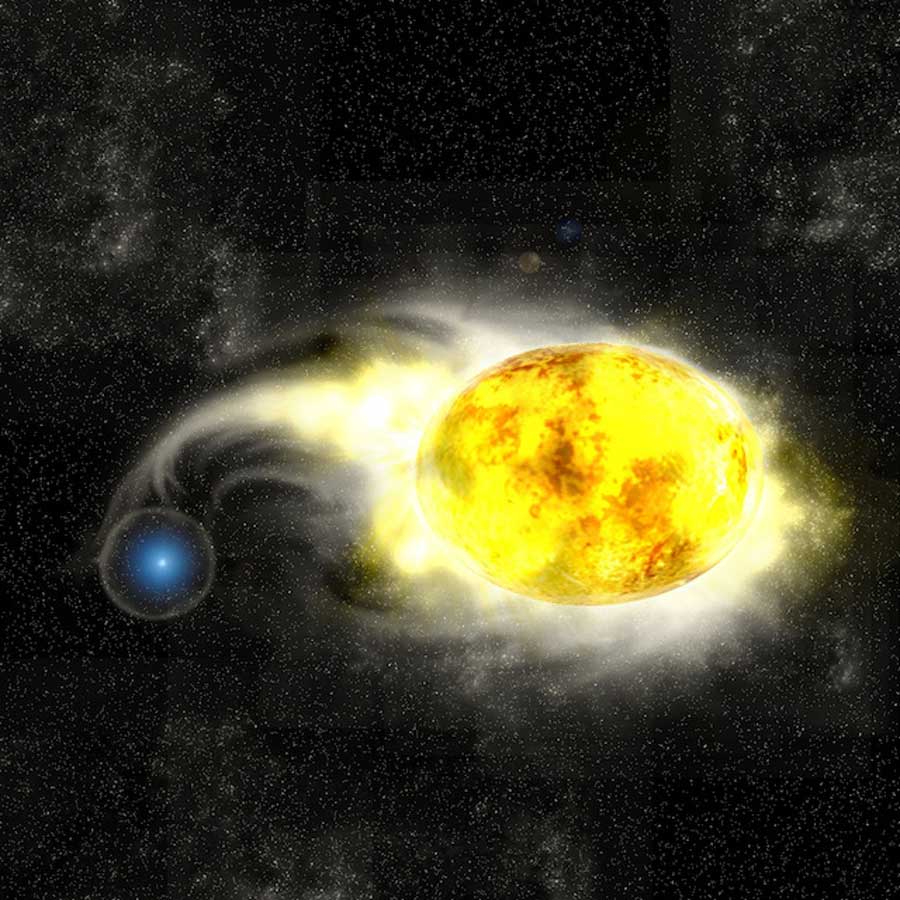

Related with question (1), there are two main mechanisms proposed for stars to get rid of their outer layers: strong winds and mass transfer in interacting binary systems. For the former mechanism, it is believed that the star should have a mass at the time of birth larger than approximately 25 times the mass of the Sun for the wind to be strong enough. Hydrodynamical models, however, set a strong constraint on the mass of the progenitor star. They found that its core could not have been more massive than eight times the mass of the Sun, which implies that the initial mass of the entire star was less than 25 times the mass of the Sun. With this possibility ruled out, they tested the alternative of a system in which the progenitor transferred mass to a close companion, thereby losing most of its outer envelope. The binary scenario has the advantage of introducing a natural mechanism for lower mass stars to expel their envelopes.

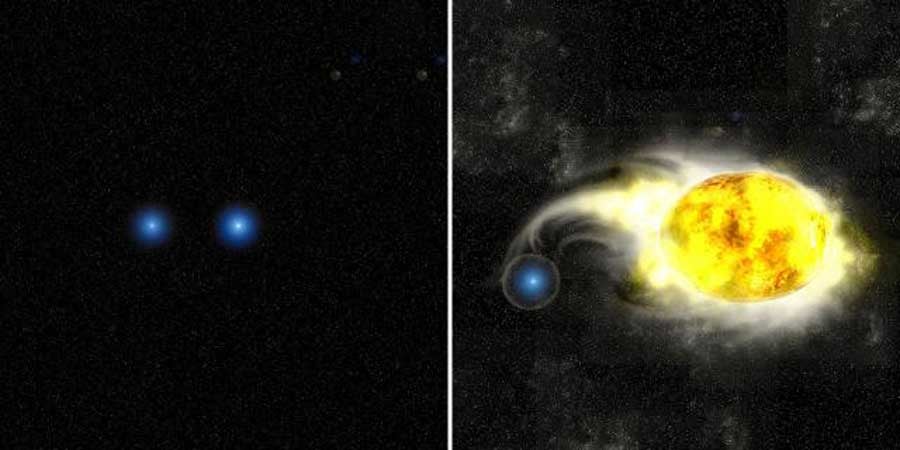

Finally, the binary models predict that the accreting companion object should be a massive blue star at the moment of the supernova explosion. Because of its high surface temperature, the companion star should emit mostly in the ultraviolet range, with negligible contribution to the total flux of the system in the optical range. The companion was faint enough so that it was not detected in the pre-supernova images of the space telescope. Their calculations thus predict that in the near future, once the supernova has faded enough, the companion could be discovered with deep observations in the blue range of the spectrum. This would constitute a definitive test for the validity of the model.