Designated Kappa Andromedae b (Kappa And b), the new object has a mass about 12.8 times greater than Jupiter’s. This places it teetering on the dividing line that separates the most massive planets from the lowest-mass brown dwarfs. That ambiguity is one of the object’s charms, say researchers, who call it a super-Jupiter to embrace both possibilities.

“According to conventional models of planetary formation, Kappa And b falls just shy of being able to generate energy by fusion, at which point it would be considered a brown dwarf rather than a planet,” said Michael McElwain from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “But this isn’t definitive, and other considerations could nudge the object across the line into brown dwarf territory.”

Massive planets slowly radiate the heat left over from their own formation. For example, the planet Jupiter emits about twice the energy it receives from the Sun. But if the object is massive enough, it’s able to produce energy internally by fusing a heavy form of hydrogen called deuterium. (Stars like the Sun, on the other hand, produce energy through a similar process that fuses the lighter and much more common form of hydrogen.) The theoretical mass where deuterium fusion can occur, about 13 Jupiters, marks the lowest possible mass for a brown dwarf.

The discovery of Kappa And b also allows astronomers to explore another theoretical limit. Scientists have argued that large stars likely produce large planets, but experts predict that this stellar scaling can only extend so far, perhaps to stars with just a few times the Sun’s mass. The more massive a young star is, the brighter and hotter it becomes, resulting in powerful radiation that could disrupt the formation of planets within a circumstellar disk of gas and dust.

“This object demonstrates that stars as large as Kappa And, with 2.5 times the Sun’s mass, remain fully capable of producing planets,” Carson said.

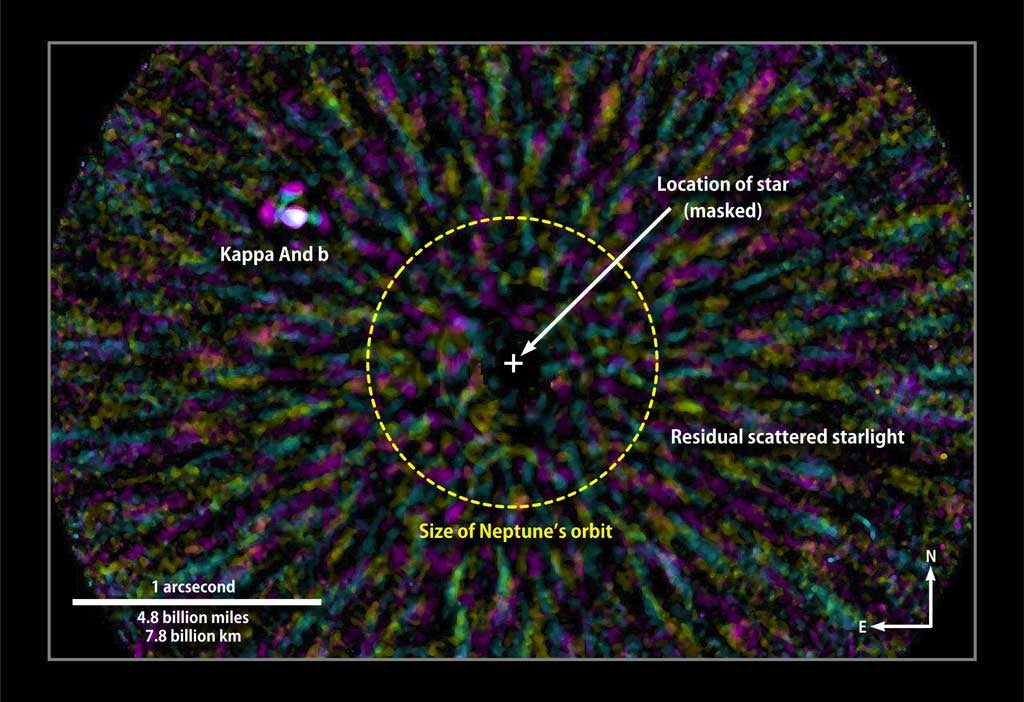

The research is part of the Strategic Explorations of Exoplanets and Disks with Subaru (SEEDS), a five-year effort to directly image extrasolar planets and protoplanetary disks around several hundred nearby stars using the Subaru Telescope on Mauna Kea, Hawaii. Direct imaging of exoplanets is rare because the dim objects are usually lost in the star’s brilliant glare. The SEEDS project images at near-infrared wavelengths using the telescope’s adaptive optics system, which compensates for the smearing effects of Earth’s atmosphere, in concert with its High Contrast Instrument for the Subaru Next Generation Adaptive Optics and Infrared Camera and Spectrograph.

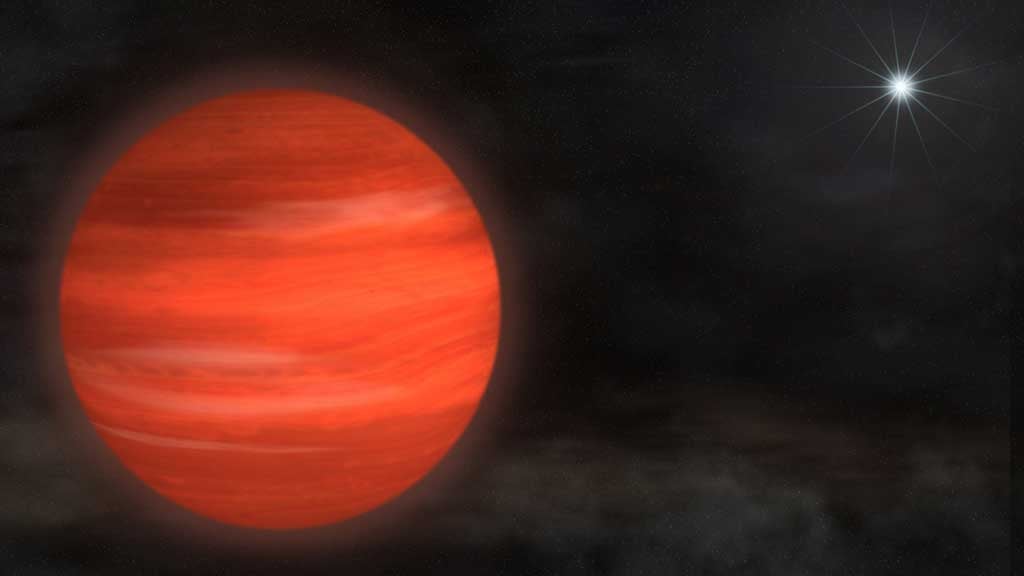

Kappa And b orbits its star at a projected distance of 55 times Earth’s average distance from the Sun and about 1.8 times as far as Neptune; the actual distance depends on how the system is oriented to our line of sight, which is not precisely known. The object has a temperature of about 2600° Fahrenheit (1400° Celsius) and would appear bright red if seen up close by the human eye.

Carson’s team detected the object in independent observations at four different infrared wavelengths in January and July of this year. Comparing the two images taken half a year apart showed that Kappa And b exhibits the same motion across the sky as its host star, which proves that the two objects are gravitationally bound and traveling together through space. Comparing the brightness of the super-Jupiter between different wavelengths revealed infrared colors similar to those observed in the handful of other gas giant planets successfully imaged around stars.

The SEEDS research team is continuing to study Kappa And b to better understand the chemistry of its atmosphere, constrain its orbit, and search for possible secondary planets.

Coincidentally, the stellar association that hosts Kappa And b also includes another famous high-mass star, HR 8799, which is one of the first where astronomers directly imaged an extrasolar planet. The system hosts several gas giant planets with masses and infrared colors similar to Kappa And b.